Inuit-built app launches at Arctic conference in Halifax

Online platform allows Inuit to record and share knowledge of land, ecosystems

caption

Candice Pedersen, SIKU team member, is joined by the rest of the SIKU team on stage at the Halifax Convention Centre.A new web and mobile social platform made by Inuit, for Inuit, is mobilizing the knowledge, languages and skills of hunters, youth, elders and community members in the midst of a changing Arctic.

SIKU: The Indigenous Knowledge Social Network was publicly launched at the ArcticNet Annual Scientific Conference at the Halifax Convention Centre on Wednesday.

The mobile app and web platform are now available online, where people on the land can access information about weather and ice safety in Inuit languages. They can also share hunting stories and knowledge of the land.

caption

The SIKU app allows users to create a profile, document trips, add observations and more.“It’s really good with SIKU that it’s a safe space for Indigenous peoples to post their hunting stories and observations,” Candice Pedersen, a member of the team that developed SIKU, says in an interview at the launch.

“With the terms and conditions that are set, we have to respect Indigenous peoples, and you own all your information and data.”

Pedersen grew up in Iqaluit, Nunavut. She works to centre Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit — which, in its simplest translation, can be described as the Inuit way of knowing, customs and values — in research taking place in the North.

She has been part of sharing SIKU on the international stage, including at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany, this past June.

SIKU allows agency and ownership over information posted to the platform. For example, Inuit posting photos and information about species on the land can choose who sees their posts — be it a select group of community members or researchers they are working with to gather data on ecosystem changes.

The photos and information they share are owned by them, not SIKU — something the SIKU team sees as key to self-determination in Indigenous communities.

The platform includes maps, user profiles, commenting, sharing, GPS with traditional place names, weather, tides, satellite imagery, and ice safety information.

Before SIKU, hunters on the ice would have to visit multiple websites to see this information, something that is difficult when hunting in areas far from Wi-Fi or data connection. SIKU offers all of this information in one place and in an offline mode.

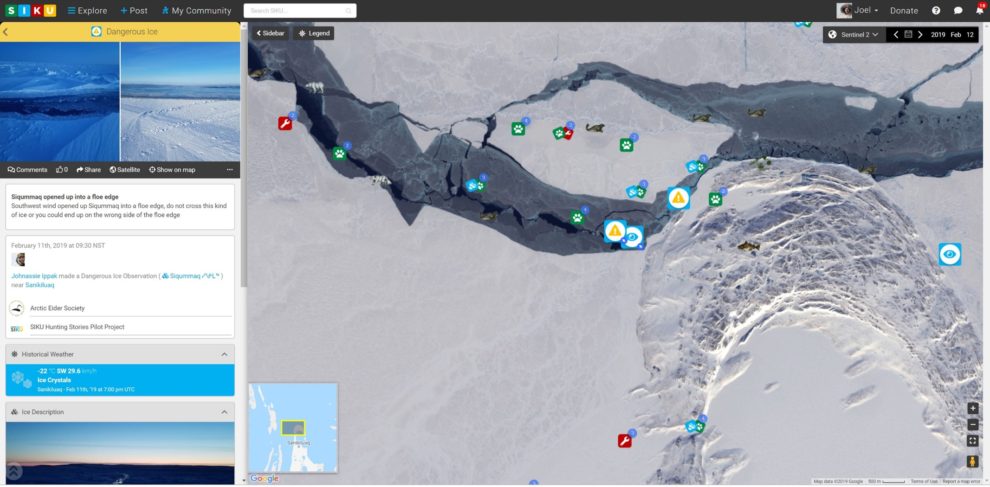

caption

The web platform displays posts about dangerous ice, including terminology in Inuit languages and satellite imagery.During the launch, team members shared how critical this information can be. For example, ice conditions can change drastically within a matter of hours — changes that are further exacerbated by climate change — meaning hunters can be stranded or fall through the ice.

The platform also provides a new way to pass knowledge from generation to generation.

Technology built on relationships

In 2017, the Arctic Eider Society, the charitable organization based in Sanikiluaq, Nunavut, that spearheaded the SIKU initiative, won the Google.org Impact Challenge, worth $750,000.

James Henry, who works with Google and is the liaison between Google.org and the SIKU team, says SIKU’s privacy policy is a “fresh approach” in the technology industry.

“Any of the individual components of technology that SIKU leverages, those individual components themselves are not necessarily revolutionary,” says Henry. “But the way that the Arctic Eider Society has brought those together within SIKU is, in a sense, revolutionary.”

Evan Warner, a filmmaker from Wolfville, N.S., and another member of the SIKU team, first got involved with the Arctic Eider Society through his work on the film People of a Feather.

Warner says the story of SIKU is one of “long-term relationships.” It’s not a platform that came to life overnight, he says, but rather developed in stages in collaboration with around 50 groups.

When it comes to scaling SIKU, Warner says there has been interest in the platform from Indigenous communities around the world. He says that in any efforts to spread SIKU, a grassroots approach is key.

“It would be really important to find groups there that would want to be the champions of it, and we could support them, but they would be the ones working with communities,” he says.

About the author

Amy Brierley

Amy is a journalism student at the University of King's College. She calls Antigonish N.S.--and more recently, Halifax-- home. She cares a lot...