It’s a fact

caption

A person looks through a magnifying glass at the definition of the word fact.Is it fact or opinion? Fact-checkers are revealing the truth

Angie Holan is sitting at her desk, lost in the chatter of the newsroom around her. Phones ringing, keyboards clicking, pens stroking across pieces of paper. It is March 25, 2008, and her thoughts are interrupted by the sound of her telephone ringing, the light on the base glowing with every pulsating sound.

A source is returning her call to confirm the answer to a question she had asked earlier that day. After a few minutes the call is over, and she began to write this headline: “Video shows tarmac welcome: no snipers”. And just like that Hillary Clinton’s pants are on fire.

Holan has worked for Politifact since the beginning. She started in 2007 as a fact-checking reporter and after thousands of checks was made editor at the end of 2013.

In her time with Politifact Holan has seen the organization grow from four reporters in a corner of the Tampa Bay Times newsroom, to 11 reporters spread across the U.S.

The first organization of its kind, Politifact’s “main mission is to give people the information they need to govern themselves in a democracy,” Holan says.

In 2016 the number of fact-checking enterprises increased by more than 50 per cent, bringing the number to more than 161 fact-checking sites worldwide. Today in the U.S. there are 50 fact-checking sites, more than ten times the number in any other country.

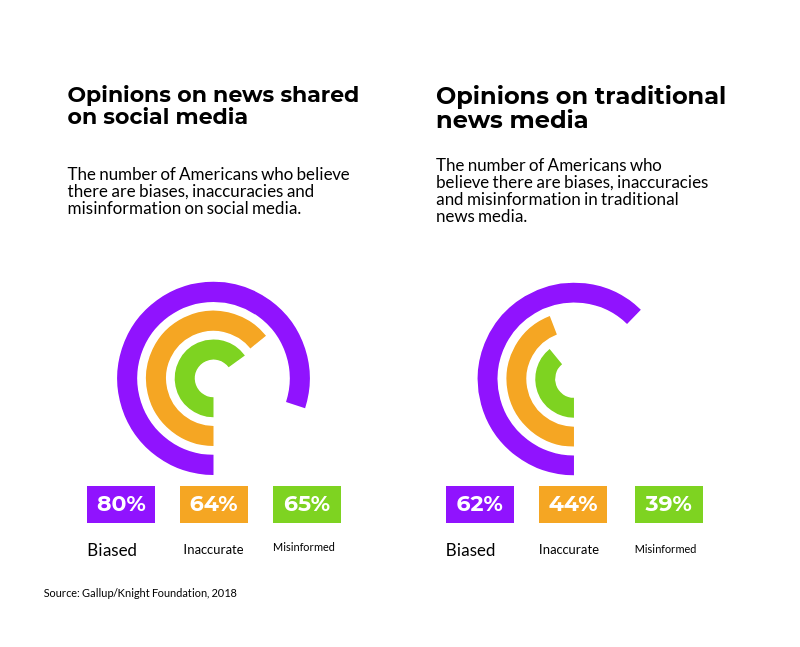

Due to the rise of social media, journalists are no longer in a position where they can drive the conversation around news. Though more news can be shared faster than ever before, there is also a rise in the number of inaccuracies shared. To combat this, fact-checkers are trying to work faster and smarter in the era of online news.

Fact-checking foundations

One of the earliest cases of fact-checking was done by the Bureau of Accuracy and Fair Play, in 1913. Founded in New York by Ralph Pulitzer and Isaac White, the bureau focused on identifying mistakes in print reporting while looking to expose “deliberate fakes.”

At the time, blame was usually placed on writers, meaning if inaccuracies were pointed out, the writer would take the fall rather than the publication.

Articles were rarely checked for inaccuracies prior to publication. This remained standard for many publications until 1923 when TIME magazine introduced a research department to check for inaccuracies in articles before they were published.

In the beginning, the department consisted solely of one woman named Nancy Ford, but by 1938 grew to 22 women researching and fact-checking. The practice of fact-checking quickly became widespread and departments were developed, similar to the one at TIME, at publications including the New Yorker in 1927 and Newsweek in 1933.

For decades fact-checking departments were introduced in newsrooms across North America. Their goal was twofold: to hold people in power accountable, and to ensure truthful, unbiased reporting.

In the 21st century things began to change, with the arrival of the Internet.

Opinion vs. Fact

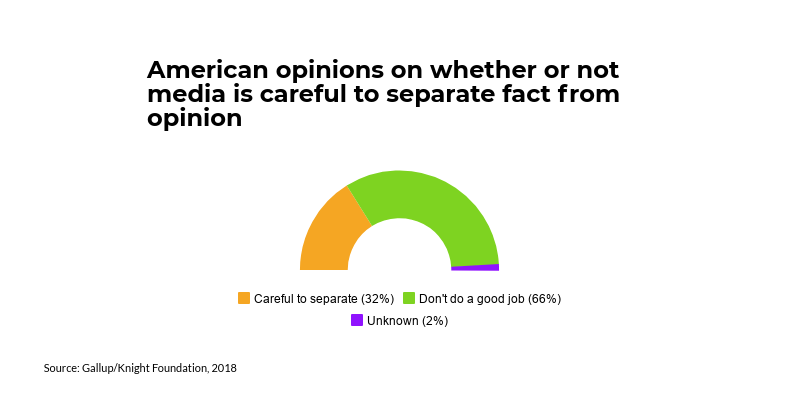

Fact-checkers, especially in the U.S., are leading the way in determining what is fact and what is an opinion. The struggle, however, is convincing partisan-driven audiences of the difference.

Jane Elizabeth, former Director of Accountability Journalism at the American Press Institute (API) in Arlington, Va. has worked extensively on the issue of partisan biases and fact-checking.

According to Elizabeth, the 2016 elections highlighted the struggle journalists face to present a fact, and not have it be discredited due to political opinion.

“What matters to them is what their political party believes. They’re going to believe them over the facts because that’s the world they live in,” Elizabeth said.

Fact-checking reporter Daniel Funke at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Fla. agrees. He believes the 2016 election sparked an interest in fact-checking in people all over the United States, no matter the party they support.

“I think misinformation has always been around, but its weaponization used during elections has a lot of people concerned. Fact-checkers are a natural way to address that concern.”

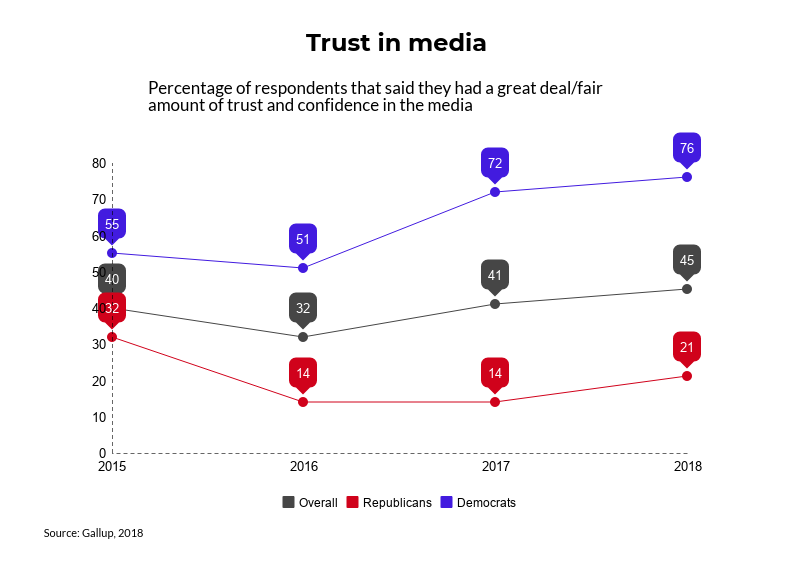

According to Funke, even though interest in fact-checking has increased, public trust in news media is still limited. So are journalists doing a good enough job separating fact from opinion?

Unbiased journalists?

Samantha Putterman, a fact-checker for Politifact in Washington, finds it easy to set aside her political opinions when fact-checking. Her work is mainly focused on proving or disproving statements made in the 2018 U.S. Congressional elections, looking through claims made by both sides of the race.

“You would think it’s hard to not feel something or want something to be a certain way, but I think because it’s fact-checking and because you’re supposed to look at things very literally, I find it kind of easy to not get personally involved,” Putterman said.

To ensure checks are truthful and unbiased, Politifact has created a system where each fact has to go through three levels of editors before they’re allowed to be published. It does this in the hope of eliminating any question of political bias, says Putterman, and to ensure full transparency. But readers don’t necessarily believe it.

In a deeply divided country, American journalists are struggling to convince readers what is true. There is at least one innovation, though, that seeks to make fact-checking easier and eliminate political biases across the board.

A 2015 study by API discovered the amount of misinformation on Twitter alone outweighed the efforts of fact-checkers 3:1. With large amounts of misinformation, fact-checking enterprises have had to rethink the way they work. In the last year, automation has been introduced to try and fill the gap.

‘Robot intern’

A leader in automated fact-checking is the U.S.-based fact-checking Reporter’s Lab at Duke University in North Carolina. In 2017 the lab developed a computer-based model to help aid in finding checkable claims and highlight their importance to the newsroom. The model’s purpose is to allow for more information to be checked at a faster rate, allowing for less misinformation to gain traction.

To do this, the service automatically looks through Twitter feeds of politicians, political parties, and political advocates, as well as CNN transcripts. It automatically checks those items, matching the claims with existing fact-checks when possible.

“It’s like a robot intern that helps them look for potential stories,” says Mark Stencel, a professor and researcher at Duke.

On top of this work, the lab has used its algorithm for automating fact-checks through partnerships with major social media companies including Facebook and Google. The goal of these partnerships, according to Stencel, is to make sure factual information is being shared more often and efficiently online.

The project works through a system of automated fact-checks and user-reported inaccuracies. This means users on Facebook and Google can report an article or claim they believe to be inaccurate. The claim will then go through the algorithm, and if proved inaccurate is flagged.

The project does not, however, remove inaccurate information. It instead gives priority to proven information at the top of searches and news feeds, and suppresses what is considered inaccurate.

Fact-checking organizations working with the Duke program are able to fully cast aside political biases, allowing the algorithm to decide what’s true, not the fact-checkers.

Duke also released an IOS app called Fact Stream earlier this year, to allow for advancements in automation to be more accessible to the public.

Similar to live-tweeting, its purpose is to allow for live fact-checking during major news events. The platform shows fact-checks automatically, so audiences can know whether or not something is true on the spot.

“What they’re doing with automation is extraordinary,” says Holan. She says fact-checking was once a niche in journalism, and the steady advances she sees allow for facts to be more widespread than ever before.

“This is journalism that’s mission-based and that’s really grounded in journalism ethics of truth, transparency, accuracy and fairness,” Holan says. “Realistically we’d like to be sustainable, but that’s not the goal here. The goal is to do good journalism and help the public understand politics better.”