Wellness

Language, work balance are keys to addressing mental health: panel

New data show mental illness, anxiety and stress disorders are prevalent

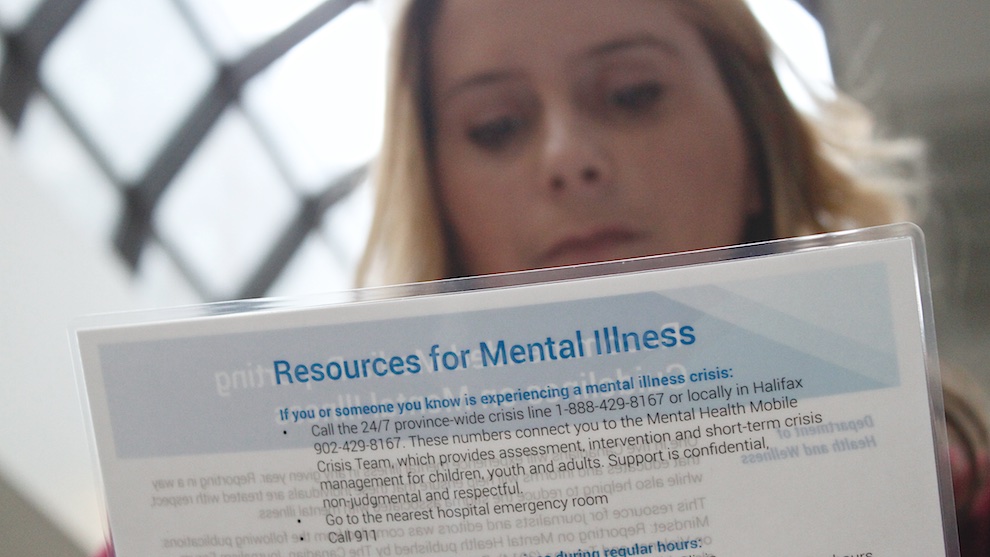

caption

Lyne Brun reviews a newsroom resource prepared for media by the Mental Health Foundation of Nova Scotia.

caption

Lyne Brun reviews a newsroom resource prepared for media by the Mental Health Foundation of Nova Scotia.In 2003, Lyne Brun had what she calls an epic meltdown at work.

“It was in front of my co-workers, in front of my peers and in front of my boss,” says Brun. “As you can imagine, it was embarrassing. It was humiliating for something like that to happen in the workplace.”

Brun says she experienced a trauma earlier in life that she didn’t deal with properly. She says she battled depression throughout her adult life culminating in the crisis that made her take a leave of absence from her job. Related stories

When she returned to work, she began to share her story with her co-workers. After one presentation, a colleague approached her.

“I heard you went right crazy,” he said, looking her right in the eyes.

On Wednesday, Brun, who works at Emera in Halifax as a peer support specialist, was part of a panel discussion that examined the language we use to describe mental illness.

Panelists cautioned against innuendo that could reinforce stereotypes of those experiencing mental illness being violent, dangerous or volatile. They suggested journalists be careful not to suggest a mental illness as a possible explanation for criminal behaviour.

The event was scheduled to coincide with Let’s Talk day, Bell Canada’s annual initiative to raise awareness and encourage mental health dialogue.

caption

Panel of practising journalists and mental health leaders. From left to right: Starr Dobson, Lyne Brun, Ken Kingston, Pauline Dakin and Mary Pyche.Brun’s crisis 13 years ago was a turning point for her. She acknowledged her colleague’s comment as one way to put it. He paused and then told her: “I think I need somebody to talk to. I just want to talk to someone… can we talk?”

Brun says she sat down and listened to him, and met with other co-workers as months went by. Her company noticed. She received a phone call from the company’s president and was given the Health and Wellness Award on the recommendations of her peers.

Before long, she had left her position to take on a new role as a peer support specialist in the company’s health and wellness department.

Today, Brun takes her lunch break every day, no matter how much work she has left. Taking breaks is important for her well-being, but it also sets an example for her colleagues as to how to manage stress.

“You’re going to see me take my lunch because if I’m going to be delivering that advice it’s important that I’m seen to be acting on it,” says Brun. “It’s about making sure people have the tools to balance work and life.”

caption

The province’s department of health and wellness operates a mental health crisis line at all times.While stigma reduction and awareness are a step in the right direction for Brun, she was concerned by what she heard at a press conference she attended earlier on Wednesday.

That morning, Morneau Shepell, a human resources consulting firm, released survey results that suggest depression is now equal to high blood pressure as a top reason why Canadians go to the doctor.

As part of its work, Morneau Shepell tracks and aggregates high-level data and trends on mental health in the workplace and provides their analysis each year.

While the data indicate a prevalence of mental health illnesses, Brun thinks there may be a silver lining. She says most of the indicators are based on treatment and support service usage.

“It’s a good thing. It may mean that more people are accessing services that they might not have in the past,” she says.

Brun sees the signs of progress all around her and recounts her own story to show others how their most difficult moments can be followed by their finest hours.

“I went from a deep dark place where I had many suicidal thoughts, to a place where I have been able to take that, and turn it into something that supports others.”