For long-term care homes in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, COVID came later, then hit hard

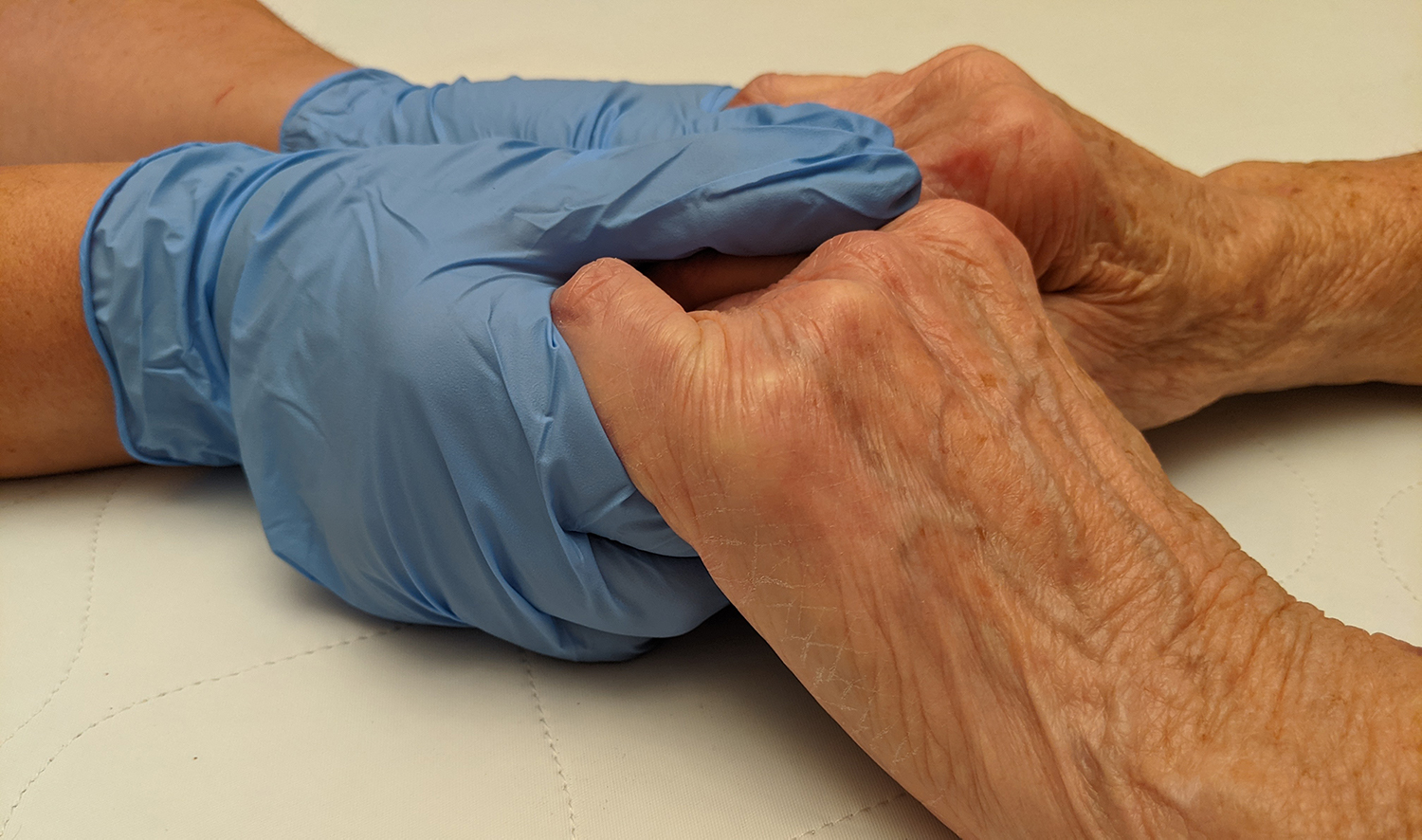

caption

Congregate living settings in Western Canada have been hit hard during the second wave of COVID-19.Experts say homes need sweeping changes to safely house vulnerable seniors

Editor's Note

These data-driven stories on COVID-19 were prepared by King's MJ students.

The very last time Lance Gauthier saw his mother, Brenda Rose Gregory, it was over a video call.

Gregory was unconscious and dying in a hospital bed in Winnipeg but because she had COVID-19 her family couldn’t be at her bedside. Instead, they had to say their goodbyes remotely.

It had all happened in a blur.

The family admitted Gregory to the Revera Maples Long Term Care Home in early October. By November 3, she tested positive for COVID-19. Two days later came the video call, and by November 6, she was gone.

“Our hearts just sank, because we knew that she most likely wouldn’t come out from it,” said Karen Bluschke, Gauthier’s wife.

caption

It was one more family’s tragedy in more than a year of tragedies caused by the pandemic.

By May 2020, only a couple of months after COVID arrived in Canada, congregate living settings — such as long-term care homes and retirement homes — were ravaged. In Ontario and Quebec, the military was called in to help overwhelmed staff.

Between March 1, 2020, and Feb. 15, 2021, more than 2,500 homes across Canada were affected by COVID-19, leading to deaths of over 14,000 residents, according to a recent report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

An alarming proportion of virus-related deaths occurred in the homes, revealing a failure to prepare the residences that house the country’s most vulnerable citizens. The large numbers of infections and deaths prompted inquiries into what went wrong and how to prevent it from happening again.

Collecting the data

Over the course of the pandemic, the Institute for Investigative Journalism, or IIJ, and the National Institute on Ageing at Ryerson University have been gathering data on care homes across the country. Using data from those and other sources, the Signal has examined the spike of infections and deaths in Saskatchewan and Manitoba during the second and third waves of the pandemic.

In the first, the two provinces largely avoided the kind of devastation that struck Ontario and Quebec in the spring. That was true both in the community at large, and in care homes. But their luck ran out as summer turned to fall, and then winter.

Manitoba had about 1,300 cases of COVID-19 on September 1, according to the Government of Manitoba website. By the end of the second wave on February 15, that rose to about 31,000.

Next door in Saskatchewan cases increased five-fold from more than 1,600 to nearly 26,700 in the same time frame, according to provincial data.

As of Thursday, there had been about 41,000 cases in Saskatchewan, and more than 38,000 in Manitoba.

Care homes mirrored the increase.

As of November 3, there had only been nine deaths in long-term care homes in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, according to data collected by the IIJ’s Project Pandemic, a Canada-wide effort to track the march of the novel coronavirus. The University of King’s College is a member institution of the IIJ.

By December 10, there had been a huge spike as the IIJ recorded at least 1,250 infections in residents in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Another 619 staff had tested positive, and there had been more than 220 deaths. The IIJ noted that some of the rise may be due to improvements in disclosure by governments.

By March 15 this year, the IIJ had recorded at least 1,737 resident infections in Manitoba, and 786 staff infections. There had also been about 463 resident deaths. The IIJ didn’t have updated data available for Saskatchewan, but the National Institute on Ageing reported 412 resident cases, 239 staff cases and 117 resident deaths in the province as of April 30.

Large outbreaks

The Maples, a 200-bed for-profit home in northwest Winnipeg, is one example of what happened.

By the end of the outbreak, declared over on Jan. 12,157 Maples residents and 74 staff members had tested positive for COVID-19, with 56 deaths connected with the outbreak.

Another example is at Extendicare Parkside in Regina — Saskatchewan’s worst-hit home. Of its 162 residents, 141 had tested positive as of December 9. The Saskatchewan Health Authority moved in to temporarily co-manage the home on the same day. The provincial health organization oversaw day-to-day operations including adjusting procedures and directing staff. Extendicare regained control on February 15.

caption

Extendicare Parkside in Regina, where heartfelt letters and notes addressed to residents were hung on an evergreen outside the facility on Dec. 12, 2020.On Tuesday last week, the Saskatchewan NDP released an internal report from the Saskatchewan Health Authority that they obtained through a freedom of information request. The report is the result of a visit from health officials to Extendicare Parkside on December 2 — one week prior to the start of SHA’s co-management of the facility.

In the report, health officials detail things going well — including staff wearing PPE, and available hand sanitizer — as well as things that are “needing support.” The NDP drew attention to two entries in the report, one a suggestion staff were “harassed” if they need to stay home because they were symptomatic, and another saying some staff had difficulty getting more than one mask (while others said they had no problem getting more than one).

Extendicare spokesperson Laura Gallant said staff had an “ample and consistent supply of (personal protective equipment),” and that staff were instructed in proper infection prevention and control practices that were checked regularly.

As for the reports of harassment, Gallant said, “All Extendicare employees across the country have been and continue to be strongly encouraged to stay home if they are feeling unwell or experiencing even mild symptoms.” She added that all staff were given paid time-off to get tested, and that time wasn’t considered as part of their sick days.

Gallant says the company takes inspections very seriously and will “endeavour to take swift action” to remedy the issues raised in the report.

caption

A sign outside the Extendicare Parkside care home in Regina, Sask. taken on December 12.On March 11, Extendicare was also served with a class-action lawsuit in Saskatchewan. In it, the plaintiffs allege that negligence of care, and breaches of contract, fiduciary duty, and standards of care led to the death or debilitation of themselves or relatives they represent.

In one instance, the claim alleges that a resident suffered from bed sores, which developed into open wounds.

The allegations have not been tested in court.

In response to the lawsuit, Gallant said, “Our focus at this time is solely on providing quality care to our residents, and supporting our families and team members.

“We share in the sadness of our community over the devastating toll COVID-19 has taken on Extendicare Parkside and other long-term care homes across the country. We’ll respond to the allegations through the appropriate legal channels in due course.”

Multiple problems

Experts contend that COVID-19 has exacerbated longstanding problems in long-term care homes, such as staffing shortages and outdated living arrangements with as many as four residents in a unit. This has combined with a lack of preparation and more widespread community transmission to spark outbreaks.

“In the first months of the pandemic, before we had vaccines, it was (like) the Titanic is going down and we’re throwing lifeboats … we’ve got to get the people off the sinking ship,” explained Dr. Carole Estabrooks, a nursing at the University of Alberta and an expert in long-term care.

“The challenge facing us now is will we build and rebuild better ships? Because nothing short of transformative change in (care homes) will prevent or mitigate the unacceptable consequences of the next major tragedy.”

Dr. Genevieve Thompson, an associate professor of nursing at the University of Manitoba, said that the majority of Manitoba nursing homes were built more than 50 years ago, meaning their layouts are not up to modern standards.

“What we have a lot here in Manitoba are care homes where there’s shared bathrooms, there’s rooms that are maybe two people, there are some that are even four in a room and that’s what happened, they’re finding, where the major outbreaks have happened here in Winnipeg,” she said.

This also showed itself to be a problem in the first wave in Ontario. A study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in August found that homes with older designs, many of which have been acquired by for-profit nursing home chains, had more severe COVID outbreaks, with more cases and deaths than newer homes.

Dr. Andrew Costa, who holds the Schlegel Chair in clinical epidemiology and aging and teaches at McMaster University, was one of the authors of that study. He said the likelihood of an outbreak occurring in the first place was most related to what was happening in the community around a facility.

“If they have it around their community, like significant infection around their community, chances are an outbreak will happen,” Costa said.

But once an outbreak got started, it was often worse in older facilities, often owned by chains.

While experts and critics say Manitoba was not as prepared as it should have been for the pandemic’s second wave, better access to personal protective equipment — commonly known as PPE — and improved knowledge of the virus spared them from a “total disaster,” Costa said.

In Saskatchewan, Debbie Sinnett, executive director of continuing care for the Saskatchewan Health Authority in Regina, said in a December interview that the authority is reviewing the care home’s processes and policies — along with others in the province — for improvements to manage COVID-19.

Running low on staff

Dr. Samir Sinha, director of health policy research at the National Institute on Ageing, has been watching the rates of infection in long-term care homes closely since the early stages of the pandemic, including infections in staff.

When staff are infected, or have had contact, they must self-isolate. This puts further strain on an already stressed workforce.

Even before COVID-19 had arrived in Canada, a report from the University of Alberta found 57 per cent of aides from 93 randomly selected nursing homes in B.C., Alberta and Manitoba missed at least one essential care task — such as bathing, dressing, or feeding — during their most recent shift because they didn’t have enough time.

The collective problems with adequate staffing of nursing homes has affected patient care, and impacted COVID-19 measures, putting homes at risk.

“When you have staffing shortages, you don’t have enough staff … to meet the basic care needs of residents and it’s hard to actually do good infection-prevention and control practices,” Sinha said.

“You have to be really particular about how you don and (remove) your PPE, how you wear your masks and all those sorts of things — and if you’re tired, you’re going to make mistakes.”

Staff reached a breaking point at the Maples home when a fraction of care aides scheduled for work were available on November 6. Some were self-isolating, while others called in sick with illnesses unrelated to COVID-19, the home’s operator, Revera Inc., said in a statement dated December 11. While some staff worked overtime to try and fill in the holes, it wasn’t enough.

That evening, staff called the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Services for help. Paramedics checked on 11 residents: three were sent to hospital, three others were given fluids and five were considered stable. One resident died of COVID-19 that evening, and another died from unrelated causes, according to Revera.

In a statement released in the days following, the Manitoba Nurses Union said that the nurses at the facility had submitted 47 workload staffing report forms — which nurses can use to identify staffing issues — for staffing shortages this year, compared to only 14 filed last year.

“According to reports, sometimes just one nurse is assigned to care for 40 or 60 residents, and they are frequently short health care aides as well,” president Darlene Jackson said in the statement.

The Signal made multiple attempts to contact Revera by phone and by email about their operations at facilities, such as the Maples, during COVID-19, but the company did not provide comment. Revera operates seniors facilities in six provinces and is owned by the Public Sector Pension Investment Board, a crown corporation that invests pension funds of many federal employees.

Mapping outbreaks in Winnipeg

The map shows Winnipeg care homes that have had outbreaks (data from the National Institute on Ageing), though as of April 28, all had been resolved. The zones are community areas, and the colours show the rate of cumulative COVID-19 infections as of April 30. Data from the National Insitute on Ageing.

View larger map

Maples review

In November, a week after the call for help from Revera staff, the Manitoba government tasked the former associate deputy minister of health in B.C., Dr. Lynn Stevenson, to lead a review of the outbreak at the Maples.

The external review, presented by Dr. Stevenson on Jan. 15, said that Maples was “viewed positively” by residents, families and health authorities prior to the outbreak.

Going into the second wave, it appeared that Revera had done a significant amount of planning, the review said, but its plans did not identify how to address the loss of staff that occurred.

That staffing shortage, alongside potentially inconsistent cleaning techniques and the absence of an Infection Control Practitioner on site, were considered the three key drivers to the outbreak in the facility.

The review made 17 recommendations that spanned from the facility level to the provincial level, as well as some additional considerations — all of which the province says it will implement.

Some of those recommendations include revising the Maples’ outbreak plan, deploying more onsite Revera resources at the beginning of outbreaks and revising the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority pandemic plan to “ensure adequate support for (personal care homes) in Winnipeg.”

Manitoba’s handling of the pandemic in care homes was a subject of debate. The opposition argued that the provincial government didn’t prepare, despite seeing how care homes were devastated in some Eastern Canadian provinces during the first wave.

The government disagreed, saying they spent several months preparing, including implementing restrictions, and new requirements.

Now, as vaccines roll out, care homes are a priority. In Saskatchewan, the provincial government has allowed care homes to open their doors to visitors as long as a home has vaccinated at least 90 per cent of its residents and it has been at least three weeks since the last round of second-dose vaccinations.

Of the 151 long-term care homes and about 250 personal care homes in the province, 60 have so far been included in the list of eligible care homes.

In Manitoba, officials have recently allowed care home staff to expand their employment to multiple locations, if they’ve received the first dose of vaccine and it has been at least two weeks since their first dose.

Staff employed at multiple locations was not uncommon prior to the pandemic but was restricted to curb viral transmission between homes.

Finding a national solution

Of course, the tragedy in long-term care is a national one and Quebec, Ontario and Nova Scotia were hit hard in the first wave. Ontario’s minister of long-term care Dr. Merrilee Fullerton recently received the final report from Ontario’s Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission. It was established last summer to determine the cause of the spread in care homes there and found that the province was ill-prepared for the pandemic, despite the warnings from SARS in 2003.

“Facility design and overcrowding contributed to the excessive long-term care fatalities that haunt this report. This supply problem must not be allowed to fester further,” the commission said in the report.

The 322-page report has 85 recommendations, including on pandemic planning, residents’ rights, infection prevention and control, staffing and funding.

Fullerton said she looked forward to reviewing and incorporating the recommendations “into our ongoing efforts to fix the long-standing issues that have challenged Ontario’s long-term care sector.”

She said many recommendations are in line with processes already underway, including stronger infection prevention and control measures and increased staffing. She didn’t commit to implementing all of the recommendations, however.

Internal report

For its part, Revera recruited 10 expert panelists to review its processes, and provide recommendations. Panelists laid out about 50 recommendations in the document, with responses from Revera on their feasibility, or completion, under each suggestion.

Some recommendations, such as proper access to PPE and limiting care workers to single homes, have become common in jurisdictions since the first wave ended.

Other recommendations — such as reducing the number of residents per room and per home, more extensive infection prevention and control training, and creating more full-time positions for staff — will need to be pursued over the long-term.

These suggestions, Revera says in the document, take time to implement or require broader structural change of how care homes are run.

Costa is among care home experts who hope these larger changes aren’t swept under the rug after the pandemic.

“Some of the things that people thought were uniquely bad to long-term care — like the lack of air conditioning, living your life with three other roommates in a small room, those kinds of issues that came to light because of COVID — they’ve been there for a long time.”

That’s why after losing her mother-in-law, Karen Bluschke is petitioning to introduce an independent office of the Manitoba Legislature to advocate for seniors and hopefully prevent future tragedies in long-term care homes.

“I was realizing there isn’t such an office here like that … and I just couldn’t understand why we wouldn’t have that,” she said.

Bluschke used the Office of the Seniors Advocate in B.C. as an example. It was established in 2014 and as the first of its kind in Canada. She’s working on getting 10,000 signatures — about 2,800 more than the number of signatures she has now.

“Seniors are just entirely forgotten about, and one day we’ll be seniors here and I want to know that as we get older that there will be maybe something in place to protect us a little bit better than what there is right now.”

About the author

Dayne Patterson

Dayne Patterson is a recent graduate student at the University of King's College. He's reported from all over Canada, including B.C., Alberta,...