Minor hockey players fight two-front battle against toxicity

caption

Cyberbullying has become an issue in Canadian minor hockey and has forced players to leave their teams due to reported incidents.Youth hockey players navigate through social media and on-ice battleground in a game meant to be fun

Editor's Note

The following story contains references to sexual assault.

Like most other young people in Canada, minor hockey players are contending with issues surrounding social media.

In some cases, players face bullying from their own teammates, while in others, harassment from fans, parents and the public swamp their social media accounts. For some, it’s enough to drive them from their sport altogether.

Tavin Rollins, a 14-year-old goaltender, was a member of the Brantford, Ont., Minor Hockey Association until February 2025, when cyberbullying forced him to find a new minor hockey team.

A spat between Rollins and some players in the team Snapchat group chat turned sideways when Rollins woke up and was added to a group chat called “Kill Tavin.” Some teammates said they were going to “step on (Rollins’) throat and rape (him).”

Rollins’ mother, Courtney Rawson, called police immediately. She also emailed the team’s coach and texted one of the Brantford Minor Hockey Association’s board members.

The team suggested she file a complaint to Sport Complaints, an independent third party hired by Hockey Canada in 2022 to handle claims of abuse in organized hockey.

Harassment reports

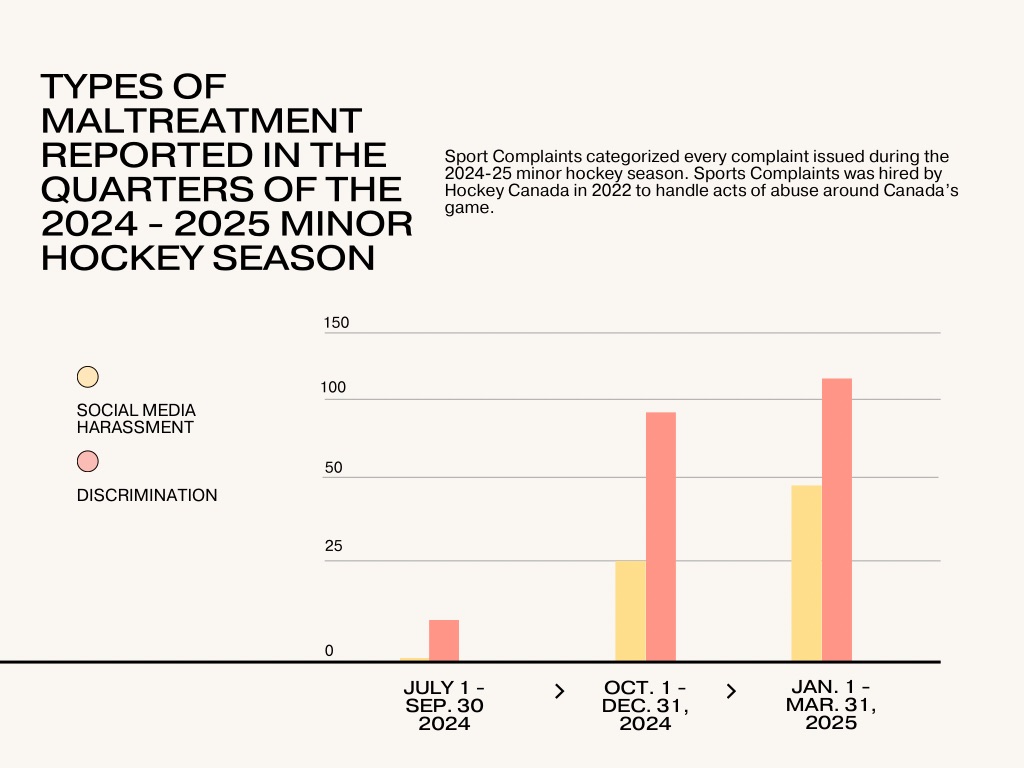

During the 2023-2024 season, Sport Complaints received 117 reports from minor hockey players in Canada related to social media harassment.

From July 1, 2024 to March 31, 2025, the agency received 68 complaints related to social media, with social media abuse peaking during the period between Jan. 1 and March 31, when Rollins’ incident happened. Those numbers indicate the 2024-25 season was on pace to surpass social media complaints from the previous year, though final numbers are not yet available.

Cyberbullies can face suspension from their organization as their highest form of punishment.

Social media is harder to control than abuse in the rink, said Matt Fredericks, president of the Halifax Hawks minor hockey organization, in an interview.

The only way Fredericks and the Hawks hear about cyberbullying is if the bullied player reports the incident, but many players are too afraid or embarrassed to say anything, he said.

Fredericks said the Hawks have had social media incidents in the past and the biggest thing he encountered is teammates bullying their peers.

“I don’t think they understand just how damaging they can be to other people,” Fredericks said. “I mean, they are still children.”

If an incident happened inside the arena, he said, Hawks coaches and officials could sort it out between players in person.

But when those players go home, coaching staffs can no longer control the player’s texts. The Hawks can prevent social media abuse in the rink, by banning phones from the dressing room and making players, parents and coaches sign a social media pledge, but what happens when they go home?

“The only prevention you can do is the education piece,” Fredericks said. “Because you can’t sit there and monitor every movement a child makes.”

The “education piece” is something Fredericks and the Halifax Hawks have emphasized, making sure every player knows the value of their words.

They have brought in Brock McGillis, the first-openly gay professional hockey player, to speak to players and emphasize the extremes of social media. The RCMP also spoke to the players.

Hockey Nova Scotia’s social media policy says any bullying, harassment or threats made towards players or officials is a violation and is subject to review by the organization’s discipline and ethics committee.

Dean Smith, the chair of diversity and inclusion for Hockey Nova Scotia, said in an interview that the policy is needed because social media is such a big part of young peoples’ lives now. He said the policy doesn’t just apply to players, as coaches and parents are also responsible for what they post.

Smith said it is the only Hockey Nova Scotia policy where the parents are attached.

“(Social media is) challenging,” Smith said. “Because what it does is it gives a voice to individuals who sometimes would not be as outspoken. It allows them a platform and an ability to make comments whether honest or racist, homophobic or whatever the case may be without having to show their face.”

These issues crop up in college sports, too. In September, sports psychologist Ryan Feron, paid a visit to the men’s soccer team at the University of King’s College.

During the session, Feron, the owner of Proactive Pause Counselling, a sport psychology company in Bedford, tried to show how teammates could positively communicate on the field.

In an interview, Feron didn’t suggest athletes fully turn off their phones. He said there is a positive side of social media, where players post achievements and get them straight to recruiters, but he sees athletes stumbling into comparison and forgetting that sports are meant to be fun.

“For a lot of these kids, it’s all about, those hearts and the likes and the comments,” Feron said. “For some, it takes away their love and that’s why we see athletes stopping competitive sport when they’re 13 and 14.”

Feron says some players are so scared to be embarrassed online they don’t take risks, which he said is fundamental in improvement.

Rollins and his mother, Courtney Rawson, declined comment due to the Sport Complaint file, which bans the two from talking to the media. The young goalie found a new minor hockey home, going back to house league with the Oxford, Ont., Warlords in February.

Inside the rink

Mark Connors remembers playing hockey for the first time with the Halifax Hawks when he was six, falling over and over again, while trying to learn the game and meet new friends.

“Every time I fell down, I just wanted to get up and continue skating,” Connors said.

Connors has lived in Halifax his whole life and is now a third-year bachelor of commerce student at Saint Mary’s University. Before then, though, he was a member of the Halifax Hawks Minor Hockey Association from six until he finished the U-18 level.

Connors’ father, Wayne Connors, told The Signal about the first time his son picked up on racial discrimination thrown at him in the rink.

“Dad, I wish I was white,” Wayne remembers Mark telling him when he was seven. “Well, I said, to me and (your) mom, you’ll always be golden.”

Mark Connors faced racism while growing up playing hockey in the Maritimes, including an instance in 2018 when he was 12 and was called the n-word by an opposing player in Tantallon.

He was later told “an n-word shouldn’t be playing hockey” by a group of minor hockey boys in the stands at a Charlottetown tournament in 2021. The players continued calling Connors slurs back to the hotel room and a parent even called Mark a “monkey.”

It’s out there now

Once the P.E.I. story hit social media, Connors’ social media blew up.

He said “99-per-cent” of the attention was supportive and about 50 NHLers, including P.K. Subban, reached out to the young goalie.

Connors did say there were a few “oddball comments.”

“I remember one guy, older fella, saying, ‘Oh this didn’t happen, I was there,’ ” Connors said. “No you weren’t, I know you weren’t. I was there.”

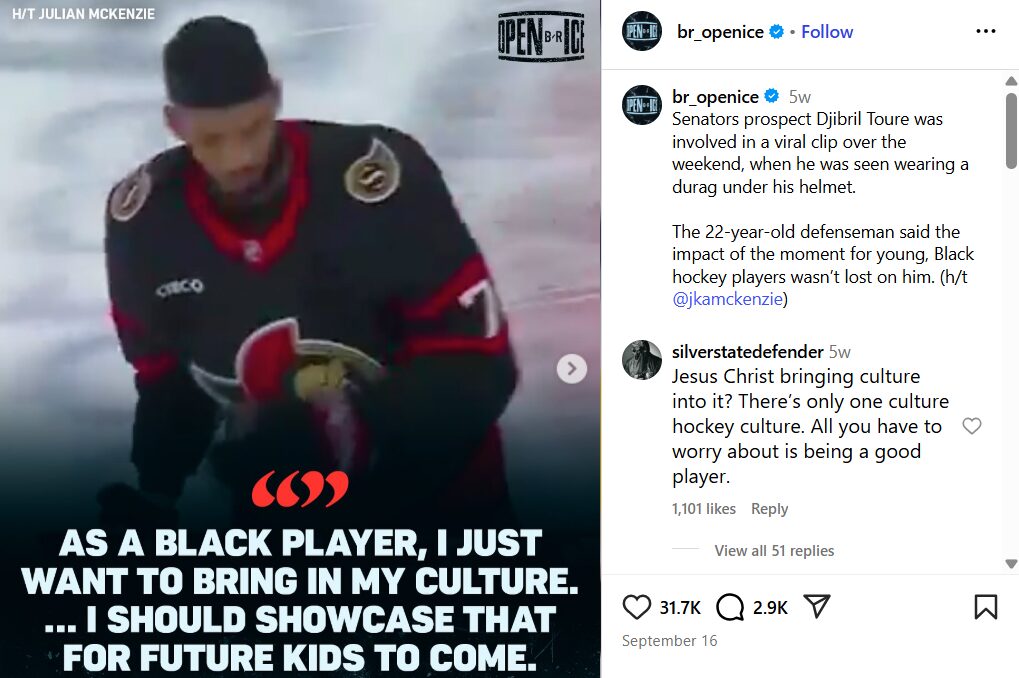

While Connors was mostly praised on social media, professional players like Wayne Simmonds and Djibril Toure haven’t been so lucky.

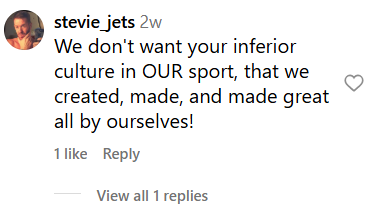

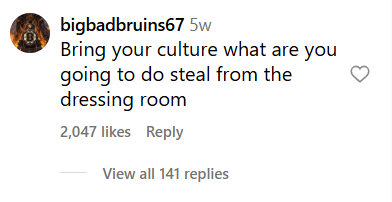

Toure is an Ottawa Senators prospect who went viral for wearing a durag under his helmet in a preseason game. Some of the comments included, “We don’t want the ice turning black, we want it to stay white…”, “We don’t want your inferior culture in OUR sport, that we created, made, and made great all by ourselves!”

Simmonds is a former NHLer who played 14 seasons, retiring in 2024. He has been an advocate for Black inclusion in hockey since a banana was thrown at him in 2011 during a game against the Detroit Red Wings.

He continues to advocate for Black inclusion, but some hockey fans still won’t accept it. A recent interview with him by the TSN television show The Shift attracted comments on the show’s Instagram page, as he was called a “woke douchebag.”

Fredericks said hockey still has a race problem due to being predominantly a white sport, while other North American games such as soccer are multicultural. He said there is more misogyny in hockey than in other sports and said it can come from the parents.

He said parents will say, “ ‘Oh, you missed the hit on that guy. Where’s the skirt at?’ ” And they don’t think anything of it because when they were younger, nobody cared that you said stuff like that.”

He said after coaching transgender and gay players, he realizes that comments like those may take away from their experiences.

Mark Connors referred to a message from Bill Riley, one of the first Black NHL players, that Connors said rings true for social media.

“Beat them on the scoreboard,” Connors said. “Just ignore them. Just ignore the hate. Ignore the negativity and beat them on the scoreboard. That hurts more.”

The pitfalls of social media

Theresa Bailey, who owns the blog Canadian Hockey Moms, where she gives advice to minor hockey parents on how to navigate politics in hockey, said in an interview over Zoom, that while young people can’t avoid social media, it’s on parents and associations to protect their children from danger.

“I think with young kids you have to stay on top of it,” Bailey said. “And if they have a team group chat … you have to be able to monitor it.”

EXAMPLES OF CYBERBULLYING

(from hockeycanada.ca)

- Sending mean texts or IMs to someone

- Pranking someone’s cell phone

- Hacking into someone’s gaming or social networking profile

- Being rude or mean to someone in an online game

- Spreading secrets or rumours about people online

- Pretending to be someone else to spread hurtful messages online

Bailey remembers an example where 12-year-old players had a ritual where they forcefully slapped each other on the back in the middle of the dressing room after every win.

One of the other players recorded this, but league policy prevented phones in locker rooms. What made it worse was that the coaching staff watched the whole thing. The video was then posted on Instagram by a player.

Bailey, who was president of the organization at the time, was shocked.

“What if CBC or CTV picked that up?” Bailey asked.

Suspensions handed out

After a lengthy review process and an interruption by the COVID-19 pandemic, the five players in P.E.I. who attacked Mark Connors from the stands were suspended 25 games from minor hockey.

The Halifax Hawks honoured him in 2021 by creating the Mark Connors Award for diversity, equity and inclusion, something the Connors feel will last forever.

Connors has stuck it out with hockey, concluding his junior career with the South Shore Lumberjacks and now coaches high school hockey. He also has volunteered as a coach in Dean Smith’s Black Youth Ice Hockey Program, which builds a safe environment for grassroots African Canadian players.

He even found junior friendlier than youth hockey.

“It’s probably the parents,” Connors said. “It starts there.”