Misrepresentation in the media

caption

How to correctly report across racial difference–and why it’s so important

“Natives, First Nations, Indians” Les Couchi typed into the search bar on the Toronto Star website. It was January 2017 and he was trying words that were once popular, socially accepted terms for Indigenous people like himself, a member of Nipissing First Nation in Ontario. He planned to share the Star articles about his community on his Facebook page Nipissing First Nation in Photographs. The search yielded more than 750,000 results.

Curious, he purchased a subscription that allowed him access to the Star’s archives and spent the next three months researching its coverage of Indigenous communities since the paper was founded in 1892.

Tragedy after tragedy was uncovered. A dead Indigenous boy was buried in a cardboard box; the priest called it a Christian burial. A report said the federal government would only provide dental coverage for Indigenous youth who were good students because it didn’t want to waste money on people who weren’t going to be successful. Young “squaws” were becoming popular “sweethearts” with non-Indigenous men. The language and descriptions used in Canada’s most popular weekly newspaper left him shocked.

Reporting on racial or ethnic groups other than one’s own is a delicate endeavour. Journalists help shape the way that people understand cultures, societies and the world. Word choices can cause serious offense, especially to communities with a history of being misrepresented in the media.

“If the mainstream papers of the day were calling us ‘Indians’, ‘drunken Indians’, making us look like we were right out of a cave,” says Couchi, “why wouldn’t the rest of the population think the same?”

Today, in the age of #BlackLivesMatter, the investigation into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and the immigration crisis, reporting across racial difference is not only common, but sometimes necessary for important stories to be told. So, how can journalists get it right—if they can at all?

“Racialized” describes people or groups who are characterized by racial or ethnic traits but did not make the decision to be defined that way themselves. This term accounts for race being a social construct, something that exists because people label and treat each other differently based on ethnic differences. “Reporting across racial difference” means the journalist writing a story is of a different racial group than the people the story is about.

Accuracy, fairness and diversity are all listed as pillars of reporting in the CBC’s, Toronto Star’s, and Globe and Mail’s guidelines for journalists, although none explicitly refer to reporting across racial difference. This means it’s up to reporters and editors to make judgements about these stories on a case-to-case basis.

A white person myself, I acknowledge that the privilege that comes with being white has informed my writing, experiences and perspective. The resources I have consulted and people I have interviewed who experience frequent misrepresentation of their racial group have helped form my view of the topic. Their perspectives guided the way I researched and wrote this article.

Racial identity

Does a reporter’s race matter?

Lisa Yeung says “definitely.”

With heritage rooted in China and Trinidad, she was inspired to become a journalist after noticing a lack of non-white people in magazines she loved to read. Now she’s the managing editor of lifestyle and blogs at HuffPost Canada.

Yeung says race influences the way people experience the world. This is why she believes it’s ideal for someone writing about a racialized community to be part of that community themselves.

Likely, she says, someone with that context will have a better understanding of the nuances of the topic being considered, the issues surrounding it and the appropriate language to use.

If a reporter from the same racialized group is unavailable, stories still need to be told. In this case, Yeung says journalists could talk to members of the community in the story about their experiences and be open to their insight.

It’s all about balance. It’s not okay to burden a marginalized community with educating you, says Yeung. Reporters should come to their sources prepared, knowing the community’s history and current context.

“They’re opening themselves up to be vulnerable in a very public way, and you have to treat that with respect and try to honour that as much as you can.”

Yeung says online guides are good tools to help journalists handle sensitive issues. In 2011, Duncan McCue, an Ojibwa CBC radio host and teacher of journalism at the University of British Columbia and Ryerson, created the Reporting in Indigenous Communities site. It offers guidance for every step of reporting on Indigenous people.

Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation, based in New York City and Oakland, California, in 2015 published a guide called the Race Reporting Guide with similar but more broad information that extends to all racialized groups.

“This is an evolution,” says Yeung. “This is an education. And I think it’s a very worthwhile education.”

Sensitive storytelling

In 2011, months after university graduation, Chad Lucas began his first job at the Chronicle Herald, a Halifax newspaper. Soon after, he was assigned a story about violence in Uniacke Square, a public housing area in the city’s North End, home to many African Nova Scotians like himself.

Originally, he was told to write a single article about how the city could minimize violence in the area. But he thought there was more to the story.

The stakes are high when you’re reporting about marginalized people, says Lucas. Doing it right, he says, is “a mark of a good journalist.”

He negotiated with his editor, and in the end wrote two long articles (about 1,500 words each) that focused on voices from the community. He spoke to people about stereotypes they faced and what they saw as challenges and solutions.

“If you’re willing to listen, you’re willing to be humble and you’re willing to learn from people,” Lucas says, “I think you’re doing alright.”

This means building meaningful relationships with the community and finding out what matters to them all while being mindful of journalistic objectivity. One of the worst things reporters can do, Lucas believes, is fill gaps in their story with assumptions that lead to the publication of incorrect information.

Carmen Robertson, a professor of Art History and Indigenous and Canadian Studies at Carleton University, says the way the media portrays racialized people matters because so much of their image has been sculpted by centuries of harmful stereotypes.

She says the way others perceive Indigenous people, and the lack of general knowledge about true Indigenous history, means they are not taken seriously. This renders them “voiceless.”

Robertson co-authored the 2011 book Seeing Red: A History of Natives in Canadian Newspapers, an analysis of how Canadian newspapers portrayed Indigenous people from 1869 to the early 2000s.

She believes the power dynamic between Eurocentric culture and minorities in Canada heightens the power difference that already exists between a reporter and their source. She says part of managing this inequality fairly means being as transparent as possible, reporting “with” them, rather than “on” them. Reporters should consult sources regularly, go to community gatherings and show people they aren’t just there to get a quote and leave.

caption

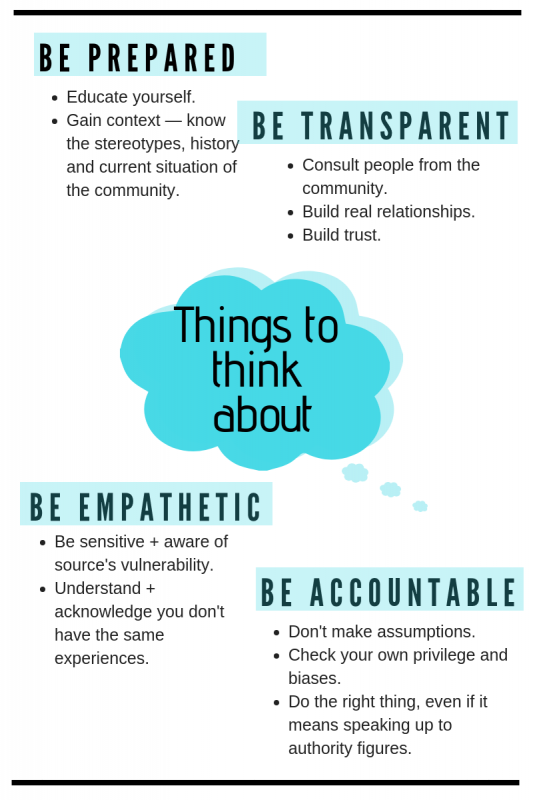

This infographic is compiled from the website Reporting in Indigenous Communities, the Race Reporting Guide, and information from people quoted in this article.

Checking privilege

But it’s not all about the sources. Idil Issa believes the first step to journalists doing accurate and fair reporting is self-criticism.

A “stickler for fairness,” Issa says she became an advocate for the rights of marginalized communities out of necessity. As a Black Muslim woman living in Montreal, she wants to be treated fairly and this is how she pursues that goal. Issa frequently appears on CBC and CTV to comment on issues pertaining to race, religion and gender.

She says journalists need to interrogate themselves and their own writing to identify their biases, and where these biases might get in the way of objectivity.

Journalists also need to let people “express their own truths,” she says. It isn’t the reporter’s place to define another person’s experience.

CBC provides employees with Unconscious Bias Training, a program that sets up an open-ended conversation for senior leaders to ask themselves about their own biases. The goal is for them to become aware of filters they may not have acknowledged before, and explore how these preconceptions affect their work.

“It’s natural and normal to be biased,” says Lisa Khoo, senior producer at CBC in Toronto and coordinator of the program. If people consume media tainted by bias, though, it will resonate in that audience.

“We’re answerable to the public for that.”

Nothing can replace experience

As Couchi immersed himself in his 125 years of Toronto Star research, he saw an upwards trend of more informed and fair reporting. He says journalists today have a better understanding of what is appropriate when it comes to reporting on Indigenous people, but there’s still work to be done. Some stories, Couchi believes, are simply better told by the racialized groups they’re about.

For him, the lived experience racialized people bring to their stories is irreplaceable.