Murder, they podcast

caption

How do true crime podcasters share compelling stories without causing harm?

Sam’s brother was murdered more than 40 years ago, but Justin Ling still had questions. It was 2018, and investigative reporter Ling was inside Sam’s apartment in Roseville, a suburb of bungalows and chain hotels outside Detroit. The police lost the trail of evidence in the ’70s.

The case went cold.

Now Ling and a CBC team were trying to warm it up. Ling spent months combing the archives, interviewing police and visiting friends and families of men who were murdered and forgotten.

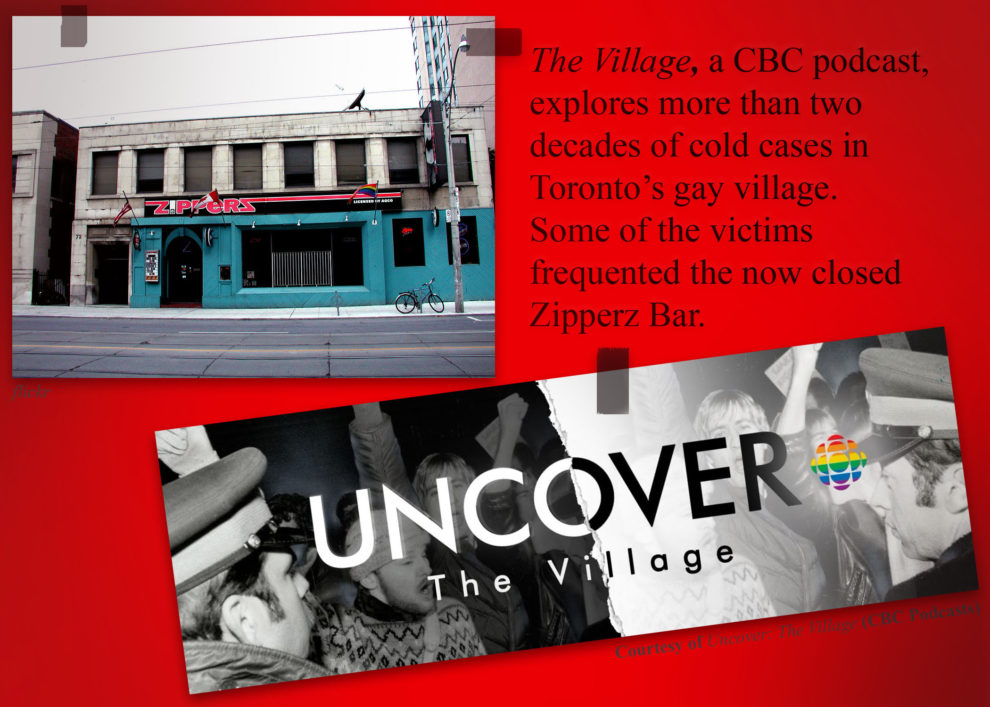

All had been part of Toronto’s Church-Wellesley village, home of the city’s LGBTQ community.

Ling’s podcast, Uncover: The Village, investigates the disappearances of gay men in the community. Since the podcast’s release in April 2019, it’s been downloaded millions of times. The crimes were heinous; the story was captivating.

This is a golden age of podcasting – podcasts are on the rise. More than 26 per cent of Canadians (and 30 per cent of Americans) listen to them monthly. There are more than 700,000 podcasts in production worldwide, and they’re a destination for advertisers targeting the upwardly-mobile crowd that enjoys them.

True crime is a dominant genre, regularly making up 25 per cent of Apple’s top 100 podcasts. Investigations like Serial and storytelling like My Favourite Murder are at the forefront of the medium. Podcasters are telling tales of murder and crime, attracting tens of millions of listeners.

With power comes responsibility – and the risk of causing harm in the pursuit of thrilling stories. How can true crime podcasters present thoughtful, ethical stories about tragedy and trauma?

caption

The Serial effect

On a morning commute four years ago, on an interstate outside Columbia, South Carolina, Kelli Boling was struggling to stay awake at the wheel. Music, news and audio books weren’t doing the trick, but when she dialed up Serial she became wide awake.

“True crime podcasts usually have story arcs in every episode,” she says. “They keep you wanting more.” The doctoral candidate at the University of South Carolina became hooked on Serial’s Peabody Award-winning investigation into the case of Adnan Syed of Baltimore, accused in 1999 of killing his high school sweetheart.

Since then, Boling has published research on true crime podcasts, including why people listen to them. Many listeners are attracted to the genre’s intimate, conversational tone. “The audience talks about how intimate it is,” says Boling. “It feels like someone is talking straight to you.”

Released in 2014, Serial hooked Boling – and millions of others – on the genre’s narrative twists and enigmatic characters. Serial exploded the genre into mainstream stardom; it’s the spark that lit the true crime fuse.

Ethical standards

Arif Noorani, CBC’s Executive Producer of podcasts, was busy editing the investigative show Hunting Warhead. Produced in tandem with Norwegian newspaper VG, Hunting Warhead explores a child trafficking ring operating in the darkest corners of the web, and crosses the borders of both countries. Noorani, along with five other journalists and producers, types notes onto a Google document: discussing where to put trigger warnings and how to describe sensitive content. Children are abused for viewers to see on a largely unpoliced form of the internet.

It’s a story, Noorani says, that must be told. The challenge is to tell it ethically.

“Ethical true crime” is Noorani’s self-professed passion. CBC’s podcasts must be “more than ‘this person got murdered and that’s it,’” he says. “We want to explore if there are larger forces at play.” Noorani says an ethical approach begins before production, and continues as the host spends time “connecting with the family and community of victims, not swooping in and swooping out.”

The Roseville apartment was small, and octogenarian Sam apologized. He said that he “didn’t have much to say.” Ling’s producer held a microphone in the corner of the room. Sam shut off Fox News.

Ling said, “tell me what you remember about your brother.” Sam padded down the hallway, returning with a large, framed portrait of his murdered brother, Mark Lefkoski. Then he sat down, and started to talk.

“When it comes to the friends and family who have lost a loved one,” Ling says, “it’s important to let them tell you the story.”

That takes a lot of work.

Ling spent more than 200 hours interviewing family members, community leaders and police officers, from Detroit to Nova Scotia. They offered memories of men who died, over mugs of greasy-spoon coffee or glasses of tamarind juice in lamp-lit apartments.

CBC’s Uncover, of which The Village is the third season, is a hit. Earlier seasons, on the NXVIM cult and an unsolved plane bombing, earned the show international audiences and accolades. Sarah Larson of the New Yorker praised how Ling’s reporting, in season three, “seeks out and listens to the people who felt neglected for so long.”

Someone Knows Something, another CBC podcast which investigates cold cases in Canada and the U.S, is built on thousands of hours of audio recordings and piles of notebooks. Producers spend days transcribing interviews and documenting the sounds of host David Ridgen’s investigations, often in the homes of those affected by the crimes.

“David works directly with the family members,” says Eunice Kim, an associate producer on the show. “That’s a really difficult thing to ask of people, opening those wounds.”

Dirty rotten spoilers

Aja Romano, an internet culture reporter for Vox, recalls receiving the press release for S-Town, which included a request to not “spoil the twist.”

In S-Town, a podcast from Serial’s creators, host Brian Reed winds down the dusty freeways of Woodstock, Alabama to visit John B. McLemore, an eccentric clock fixer. (Note: an S-Town spoiler is coming soon. Skip to the next section if you want to not see it.)

McLemore is convinced there’s been a murder and wants Reed, a producer at This American Life, to investigate. And then – the twist.

In the second episode, John B. McLemore dies by suicide.

No longer is S-Town about the murder (which Reed eventually proves never happened) but about the life – and death – of McLemore. It’s a labyrinthine tale of hidden treasure, back tattoos and McLemore’s sexuality. Despite the S-Town team’s journalistic experience, “they literally treated his suicide like a spoiler,” says Romano; tragedy was turned into a plot device. The Guardian and Atlantic both argued that beneath the captivating story lurk murky ethics, as Reed exposed secrets McLemore wanted to keep buried.

“If S-Town had been done by someone within the true crime community,” Romano says, “they probably could have avoided this.” Romano doesn’t think podcasts should censor violence, but should consider how it’s presented.

For some, these stories can be therapeutic. Jes Skolnik, a domestic abuse survivor, wrote in a 2017 New York Times article that “we deserve stories that reveal what we know to be true about human nature — that all of us are capable of the most terrible acts, the most incredible resilience and everything in between.”

Romano says true crime podcasts have developed a common understanding of how to discuss sensitive topics – in large part due to listener feedback. Some shows, like Casefile, an Australian show which tackles different stories each episode, inserted trigger warnings in response to fan requests. Alerting listeners about sexual violence, suicide and mental health issues creates a more inclusive listening experience.

Romano says journalists, like those who produced S-Town, “aren’t always aware of activist conversations going on in the true crime community.”

Murders on tape

“Nine gruesome stories of the worst depravity the world has ever seen,” narrates Mike Boudet, kicking off another episode of his hugely popular Sword and Scale podcast, recorded in Florida. Boudet tells tales with a morbid humour: he describes Luka Magnotta, a narcissistic murderer in Montreal, as a “one-man I.T department, a one-man guerrilla marketing and PR department, a one-man film crew.”

ǝǝɹɥ⟂ ǝposıd∃ – Available Nowhttps://t.co/apdeY6D5o4 pic.twitter.com/dtOMZKqrQP

— Sword & Scale (@SwordAndScale) October 17, 2019

Boudet touts a “no holds barred” approach to true crime. In a few episodes, he plays a recording of the murder – gruesome sounds a killer recorded in scratchy fidelity – with little warning.

Romano found Boudet’s portrayal of killers and macabre slaughters shocking. “You need to set it up respectfully,” she said, “and don’t present it as a shocking moment in a horror film.” When killers take centre stage, victims play supporting roles in their own tragedies.

Romano says true crime can stimulate discussion and raise important questions while honouring those hurt by a story. When podcasts swing to sensationalism, we’re left with blood and sadism in a killer’s basement.

The Village’s final moments unfold in Toronto’s Metropolitan Community Church, where hundreds gathered to remember the village’s victims in February 2019. It’s about an hour’s walk from the courtrooms where the killer pled guilty.

As the season’s eight-episode investigation draws to a close, Rev. Jeff Rock delivers a sombre eulogy from the pulpit. “It is no secret that there is evil, and darkness, and shadows in our world,” says Rev. Rock.

“The only way for us to overcome those shadows is to share the light, to commit to stand in solidarity with one another.”

About the author

Sam Gillett

Sam calls Orillia, Ontario home. When he's not chasing Signal stories, he can be found sketching in cafes, watching soccer or following news...