N.S. Court of Appeal hears Grabher licence plate dispute

Grabher’s lawyers appealed the January 2020 decision that banned his last name from his licence plate

caption

Lorne Grabher attends N.S. Supreme Court in 2018.Lorne Grabher’s lawyers argued in the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal on Tuesday that a personalized licence plate is part of freedom of expression.

A judge for the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia ruled last January that taking away the “GRABHER” plate did not violate the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Grabher, from Dartmouth, watched over the proceedings online remotely.

The Court of Appeal reserved their decision until a later date. Related stories

Grabher’s lawyers said that he had the licence plate for 27 years before an anonymous complaint in 2016 led to the plate being deemed a “socially unacceptable slogan” by the director of road safety with the Registry of Motor Vehicles.

“The registrar determined the plate was legal, and then suddenly said it was illegal. On what basis? What had changed?” Jay Cameron, a lawyer for the Justice Centre of Constitutional Freedoms representing Grabher, said in court.

Personalized licence plates have to be renewed every year, and the “GRABHER” plate was renewed 26 times, including the year it was deemed unacceptable.

Advocates say phrase still ‘triggering’

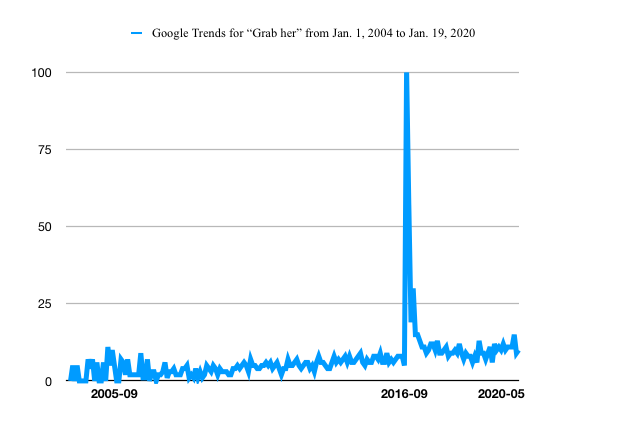

Cameron suggested he had an idea of what had changed — a new controversy surrounding Donald Trump. The Access Hollywood tape that was leaked on Oct. 7, 2016, depicted Trump on tape, years earlier, admitting to grabbing women without their consent.

“The idea that there is some causal link between offence and what Mr. Trump said in 2005 is not supported by evidence of the Crown,” said Cameron.

Dee Dooley, the legal education, training and advocacy program coordinator at the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre in Halifax, works with survivors of sexual assault.

She said seeing the Grabher case can be upsetting for survivors because of the comments Trump made.

“That particular phrase has been made into a bit of a joke,” which, Dooley said in a phone interview, has “a triggering aspect of it.”

Lawyers for Grabher argued that since there was no damage from the licence plate during the 27 years beforehand, he should be able to keep the plate.

“I understand that it’s this person’s name, but not everyone who sees that licence might know that context,” said Dooley.

caption

Google search results for “Grab her.”Grabher’s lawyers argued that the banning of certain words on personalized licence plates is breaking section 2(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms: “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.”

Lawyers for Grabher also cited section 15: equality rights. Grabher is an Austrian-German last name, and appellants noted that the name only gains meaning once it is Anglicized. They argue that the original letter saying that the plate could be “misinterpreted” as a “socially unacceptable slogan” could lead to censorship of media in other areas.

“It will be applied in areas other than licence plates,” said Cameron.

Cameron later pointed to the seemingly arbitrary rulings of the registrar in choosing which personalized licence plates are banned. He gave examples of “FENCE,” “ODD,” “PREMIER,” and “DR DAVE” as plates that he deems unnecessarily banned on the 67-page list of banned personalized licence plates.

He pointed out that in the summer of 2017, after Grabher’s plate was banned, Halifax Water ran an ad campaign on buses with slogans such as “be proud of your Dingle,” and “powerful sh*t.”

Lawyers for Crown, Grabher both say context lacking

One of Cameron’s final arguments was that the context in “GRABHER” is lacking. In the original ruling, one of the arguments from the Crown was that people could be inspired to commit acts of sexual violence because they see the licence plate.

Cameron argued that even if it was perceived in a different way, no one would base their actions just off of seeing the plate.

The Crown’s argument focused on the same issue: that there is no context to “GRABHER.”

“We’re dealing with a small space, with limited expressive availability on a plate,” Jack Townsend, a lawyer for the Crown, told the court.

Townsend noted that a personalized licence plate, versus a flyer in a public park for example, doesn’t have much room to explain it’s real meaning.

The Crown argued that personalized licence plates have always been heavily regulated. They have to have certain colours, fonts, and only have space for seven letters.

Townsend also referenced “joint speech,” the concept that speech on public property can be seen as coming from both the person and the government who “allows it space to be used that way.”

The Crown further argued that Grabher still had the right to own a car, have a licence plate, and even have a personalized licence plate. Grabher just cannot have the “GRABHER” plate.

Case history

The original letter dated Dec. 9, 2016, from Harland said the GRABHER plate would be cancelled on Jan. 13, 2017.

The legal battle over the licence plate has been ongoing since March 31, 2017. Grabher’s lawyer at the time, John Carpay, wrote a letter to the Registry of Motor Vehicles that said taking away the vanity plate was a violation of the freedom of expression under the charter.

Carpay said that if the plate wasn’t reinstated by April 6, 2017, further legal action would be taken. The plate was not reinstated. Grabher’s lawyers filed a notice of application to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia in May 2017.

The Crown commissioned a report by Carrie Rentschler, a professor at McGill University, as an expert in gendered violence in media. Rentschler’s report stated that while although Grabher is a last name, people could misinterpret it as an example of rape culture.

“For them it would not matter that ‘Grabher’ is someone’s surname,” she wrote in the report, “because it is also a statement in support of physical violence against women.”

Justice Darlene Jamieson denied Grabher’s plea for his plate on Jan. 31, 2020.

When The Signal reached out to Grabher, a woman who did not identify herself said he wouldn’t be commenting.

About the author

Emily McRae

Emily McRae is a journalist based out of Halifax, Nova Scotia.