New old-growth policy won’t change much: forest ecologist

Nova Scotia lowered old-growth forest age requirements to meet quota set in 2012

caption

A pair of hikers walk through one of Nova Scotia’s old-growth forests at Oakfield Provincial Park.Donna Berthiaume wants to let nature be. She loves walking through Oakfield Provincial Park admiring the beauty of old-growth forests.

“It’s just miraculous to me,” Berthiaume said.

caption

Donna Berthiaume stands in an old-growth forest at Oakfield Provincial Park on Sunday.Forest ecologist Donna Crossland said many Nova Scotians want to let nature be. But she doesn’t believe Nova Scotia’s new old-growth forests draft policy will do much to change “the dire situation with a near complete lack of [old growth].”

The previous policy on old-growth forests was released in 2012, with a goal of identifying eight per cent of old-growth forests or old-growth opportunities on Crown land across the province. The 2021 draft policy states that this goal was met in early 2020.

Crossland believes this statement is misleading.

“The eight per cent means you should be seeing old growth forests in a lot of areas of Nova Scotia, but we don’t see it,” Crossland said. “What they’ve done is put a lot of forests in the eight per cent allocation that are not old growth at all.”

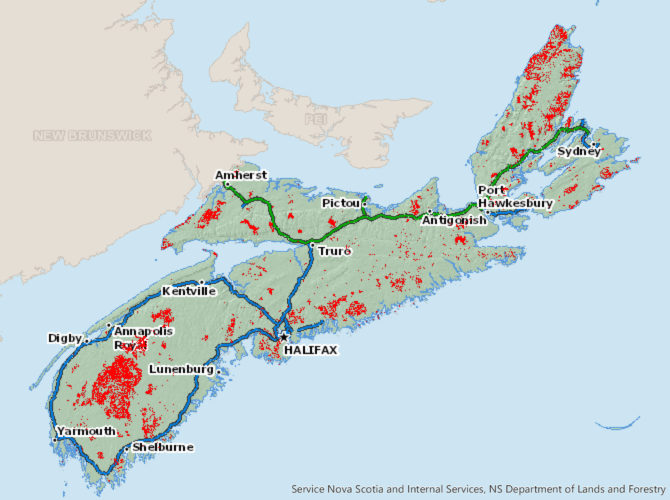

caption

The red signifies patches of old-growth forests in the province.Crossland, with the Medway Community Forest co-operative, was not involved in drafting the policy and is speaking independently of the group.

She would like to see an interim measure whereby all the remaining forest at 80 to 100 years of age on Crown land would be inventoried.

“These forests need to be protected and there needs to be no harvesting at all of those older stands of forest,” Crossland said.

She said there should be a moratorium on clear cutting on Crown lands until ecological forestry is implemented.

Peter Duinker is a retired Dalhousie University environmental studies professor. He contributed to the 2021 policy draft.

He said it’d take forever to determine an accurate number of old-growth forests in the province because it’s impossible using standard forestry techniques to tell if a forest is old growth.

He said it’s much easier to determine the age of younger forests. The province decided to lower the age requirement from 125 years to classify more forests as old growth.

“So, what the province did to make the claim that it had reached the eight per cent minimum target was include forests that are considerably younger than 125, which is much more confidently aged using the photo interpreted inventory,” Duinker said.

“They added enough of that sum of all forests in protected areas and old-growth forest on Crown land until it got to eight per cent.”

caption

Common characteristics of old-growth forests include the presence of older trees, minimal signs of human disturbance, mixed aged stands and the presence of canopy openings due to tree falls.Duinker said that classifying these younger forests as old growth will further protect them from logging operations. In order to log a section of old growth, a permit from Department of Natural Resources and Renewables is required.

He said the old-growth forest policy has an aggressive rate of replacement for when part of an old growth is sacrificed for commercial development.

“If you lose one hectare of old growth, we’re not asking for one new hectare to be purchased by the proponents and given to the Crown,” Duinker said. “The minimum is five hectares must be given to the Crown.”

Crossland said she believes the government hasn’t been doing a good job of protecting old-growth forests across Nova Scotia and no old growth should be sacrificed for commercial development.

“We need old-growth forests right now on the landscape,” Crossland said. “We must not just consider the age of trees, but it’s that old-growth forests house a greater array of biodiversity and can store carbon far better than any other forest type.”

caption

Old-growth trees are common at Oakfield Provincial Park.Peter Bush led the team in charge of drafting the policy. The forest research manager with the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables said the policy focuses on protecting all old-growth forests on Crown land and he hopes it encourages private landowners to protect old growth on their property.

Bush said the province can only apply the policy on Crown land. The policy says that 63 per cent of all forested land in Nova Scotia is privately owned.

The draft policy is undergoing public consultation. The policy team is accepting written submissions by email to ecologicalforestry@novascotia.ca until Dec. 8.

Correction:

About the author

Will McLernon

Will McLernon is a journalist with The Signal. He is currently finishing up his Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) degree with a minor in International...

L

Larry Cosgrave