Insight is needed, not stereotypes

caption

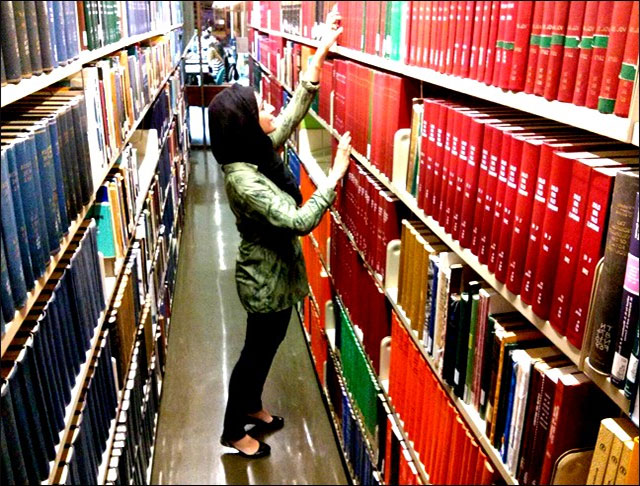

Marwa Al-Mansoob, an immigrant from Yemen, looks for readings on Arabic culture in the Dalhousie Killam Memorial Library.“No way out” is how a December 12, 2001 Halifax Chronicle Herald headline described 9-11.

“With Israeli helicopters blowing up civilians in order to murder terrorists,” the story’s opening line reads, “and Palestinian terrorists blowing themselves up in order to murder civilians, only the sunniest of optimists can now contemplate peace in the Middle East.”

A few months later, a wave of headlines appeared in the Halifax newspaper connecting Arab people to terrorism:

- “Jihad manual covers everything from hijacking to poison gas.”

- “Taliban threatens holy war; Afghanistan says it won’t give bin Laden to Americans.”

- “Islamic scholars debate suicide bombings.”

The events of September 11, 2001, fundamentally altered the way North Americans view Arab people. Fifteen of the 19 hijackers who flew four planes on 9-11 were from Saudi Arabia, while the four others were from Egypt, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates. Terms such as “terrorist” and “jihad” were now on every North American’s radar.

Marwa Al-Mansoob, a university student in Halifax, felt welcome in Canada until she watched news coverage on her people.

She immigrated to Canada from Yemen in 1995. She says because of 9-11 she’s received hurtful comments and uncomfortable stares. Al-Mansoob sees no change in the last 12 years.

“Media against Arabs is still the main thing you see. You still get the images of the crazy Arab with the American flag, yelling. Everyone judges and generalizes, saying, ‘Yeah, all Arabs are like this guy.’”

A search in the database Eureka confirms a difference in the treatment of Arabic culture and terrorism before, during and after the attacks.

In 2000 the term “jihad” appeared in 31 Herald news stories, while numbers in the following year jumped to 206. Numbers were still high a year later when 191 stories were reported.

Analysis shows the use of these words has now decreased, but they’re still higher than before 9-11. But numbers for the terms “Islamist” and “terrorist” remain high because they’ve been referenced in stories about the Arab Spring in 2011 and the current conflict within Syria.

Amal Ghazal, a professor of Middle Eastern history at Dalhousie University, says journalism organizations send North American reporters overseas who know nothing about the culture or language, and expect the audience to trust their opinion. Ghazal says reporters experience culture shock and don’t know what to do with the information.

There was this new girl in my neighbourhood… We walked up and said, ‘Hi, do you want to play with us?’ And she said, ‘No, I don’t play with Saddam’s people.’Marwa Al-Mansoob, Halifax university student

She says reporters are notorious for misrepresenting cultures and denying stereotyping. Ghazal explains it’s as easy for the media to deny stereotypes as it is for Arab citizens to complain about negative stigmas.

The problem, to Ghazal, stems from flashy news overwhelming real news. Local and American news coverage offend her so much she stopped watching. She says if the audience looks for negative stories, they’ll find them.

Ghazal watches Arabic news channels like Al Jazeera. “Doesn’t mean it’s good, but I pay attention to dynamics. How the news reaches the viewer is different, but I have (the power) to decide what I want to look at.”

Benjamin Amaya, a small man with a warm Spanish accent, sits in an office filled with piled texts and articles on minority interactions in Canada, and intercultural communication. The El Salvador native periodically touches his glasses, as if to refresh memories of the past.

The anthropologist, who teaches at Mount Saint Vincent University, says people need to question how they absorb information they get, and journalists need to learn more about the cultures they’re covering.

“Two words: study history. Go beyond the journalistic coverage. You can’t understand a culture in what is often a minute-and-a-half news clip. The time doesn’t allow for analysis.”

Following 9-11 Amaya was teaching in Cape Breton, where he says there wasn’t a strong sense of prejudice, but it was integrated in comparison to other parts of the Maritimes.

Joanne Clancy, a news director at CTV Halifax who has visited the Middle East, says 9-11 distorted everyone’s concerns about security. But you won’t find Clancy tiptoeing around overseas stories. Clancy says stereotypes of Arab people begin with issues in the media.

“In Canadian news there’s no automatic linkage (with the Arab people and terrorism). Al Jazeera shouldn’t do it either – remember, there’s the reverse as well.”

Widespread belief

According to The National UAE online, in 2011, 73 per cent of Emirian people surveyed by Al Aan TV in Dubai said they believe the Arab people are represented poorly in North American media.

Al-Mansoob, the Halifax university student, feels hate through her television. But it surprised her when she felt discriminated against in her own backyard.

“There was this new girl in my neighbourhood. My best friend from Afghanistan and I said we’d get to know her. We walked up and said, ‘Hi, do you want to play with us?’ And she said, ‘No, I don’t play with Saddam’s people.’”

It upsets Al-Mansoob that others judge her because of where she’s from and what she looks like.

Evelyn Alsultany of Michigan, author of Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation after 9/11, says a 2004 public opinion poll proved that negative media coverage about the Arab people resulted in 44 per cent of Americans believing Arabs and Muslims deserved less civil liberty. For example, 44 per cent said immigrants should be monitored by law enforcement and have their location registered with the federal government.

In 2006, a second poll was conducted, where 22 per cent of Americans said they’d never want a Muslim neighbour.

Alsultany doesn’t have a problem with Muslims being shown as terrorists in some media, but says there must be “a diverse field of representation.”

There are nearly 300 million Arabs and 1.2 billion Muslims in the world, coming from places like Southeast Asia, India and the Middle East. Alsultany says calling them terrorists fails to show the community’s humanity and diversity.

In 2009 the American Psychological Association published Muslims in America, Post 9-11, which surveyed 102 Muslims.

Of the 102, 25 per cent reported being victims of verbal assault, a similar percentage said they were harassed in the workplace, and 19 per cent reported physical assault as a result of racial tension provoked by news media.

The survey doesn’t represent the views of all Arab people, only the ones who were selected.

“I don’t think (the Arab people) are overly sensitive,” says Alsultany. “When people are portrayed one way over and over again, it leaves a mark.”

According to the research website Infoplease, the FBI said hate crimes against Arabs and the Islamic community went from 28 in 2000 to 481 in 2001, causing many people to face depression and anxiety.

Ghassan Haddad is a Lebanese immigrant who lives with his wife and children in Bedford. As he sits on his living room couch, one foot over the other, hand on head, it’s clear he’s familiar with this anxiety. He says both North American and Middle Eastern media entice people to think a certain way.

Mohammed el-Nawawy, a professor at Queen’s University of Charlotte in North Carolina says, “I feel like it’s my responsibility to teach my students about the Middle East.”

Looking to the Future

According to the 2011 Statistics Canada Census of Language, 5,175 people in Halifax Regional Municipality list their mother tongue as Arabic. Meaning Arabic is the third most spoken language in Nova Scotia after English and French.

People once unfamiliar with Arabic culture are now more up-to-date because it is growing in Halifax.

But the way news is consumed has not changed.

Consulting ethics handbooks and style guides are methods of fixing this problem.These guidelines are used in newsrooms and sometimes updated yearly. The Reuters Handbook of Journalism is a good example. The news organization last modified its style guide in 2012, advising writers that words like “jihad” should be used with extreme caution, “except in quotes (because) it has become a loaded term”.

Al-Mansoob agrees that the word should be used wisely. “Jihad means struggle. It doesn’t mean terrorism or to threaten innocent people. I get mad when people explain it that way.”

El-Nawawy, the North Carolina professor, says having more news organizations cover Arabic culture would help educate people about the issues.

Eva Hoare is a news reporter for the Chronicle Herald. She says, “As news organizations cut their budgets, I worry we won’t get as much unbiased news out of that region. And without the bureaus, big networks and newspapers in the region won’t have a balanced picture”.

But Hoare defends the Herald, saying the newspaper has always conducted balanced reporting.

“Not just in light of 9-11, but in general regarding other ethnicities. News people are people too. They’re subject to the same fears and overreactions as everyone else.” Hoare says the upsurge in coverage following 9-11 was due to excessive paranoia. But she thinks Canadian news media is in better shape than the U.S. Hoare blames stations like Fox News, whose commentators force-feed opinions to the audience.

El-Nawawy agrees that Canada is more open to exposing balanced, global issues in media. Coverage that doesn’t get at the nuance of Middle Eastern culture only lessens people’s ability to understand.

In the end, stereotypes aren’t false – they’re incomplete. It’s everyone’s responsibility to ask more questions.

“So much we don’t know defines what we think we do know,” says CTV’s Joanne Clancy.