Nova Scotia to appeal court decision finding systemic discrimination against disabled people

Premier Tim Houston said the government wouldn't appeal the Court of Appeal decision

caption

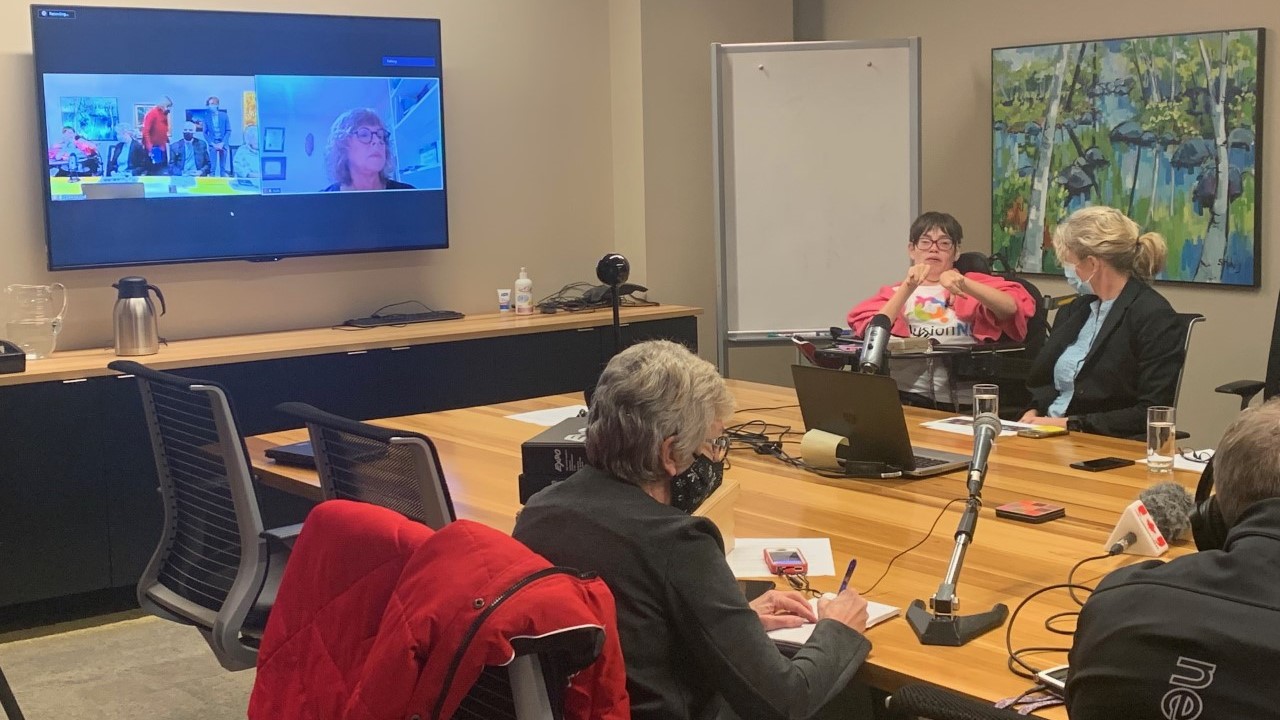

Vicky Levack (second from the left) speaks at the Disability Rights Coalition of Nova Scotia press conference on Wednesday, Dec. 1.Despite saying it wouldn’t, Premier Tim Houston’s government now says it will appeal a court decision that found systemic discrimination against Nova Scotians with disabilities.

The Nova Scotia Court of Appeal ruling rendered Oct. 6 found the provincial government discriminated against three disabled people: Beth MacLean, Sheila Livingstone and Joey Delaney.

The court ruled that, “to place someone in an institutional setting where they do not need to be in order to access their basic needs, which the Province is statutorily obligated to provide, is discriminatory.”

The decision sent the matter back to a Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission board of inquiry to determine how to find a remedy.

The day after the decision, Houston was asked during a news conference whether his government would continue to pursue the case in court.

“No,” Houston said.

“I just don’t think anyone should really have to take their government to court to make their government do the right thing. So, we received the message loud and clear, we will work with the community to make sure that the supports are in place.”

On Wednesday, nearly two months after the decision, the Disability Rights Coalition of Nova Scotia held a news conference calling on Houston to commit to fixing the systemic discrimination identified the ruling. With a meeting scheduled for Monday with the premier, the coalition also called on the government to state whether it would seek to justify the discrimination at the board of inquiry.

The Signal asked the government to comment on those questions, and received a response on Thursday from Community Services Minister Karla MacFarlane, writing on Houston’s behalf.

“Many significant questions arise from the Court of Appeal decision that we believe the Supreme Court of Canada may help us to resolve,” MacFarlane wrote.

“These questions include the impacts and implications of the systemic finding for other social programs delivered by government. Government programs are guided by policies with allocated budgets. This decision also places a legal requirement on the Disability Support Program and we need to better understand that requirement.

“For these reasons, the province has made the decision to appeal.”

MacFarlane said the government isn’t appealing the individual findings of discrimination or the money awarded to MacLean, Livingstone, and Delaney.

“I feel that what happened to Joey Delaney, Beth MacLean and Shelia Livingstone was terribly wrong – and that it does not reflect the values of kindness, respect, fairness and decency that we, as Nova Scotians, hold dear,” MacFarlane wrote.

During Wednesday’s news conference, Vicky Levack told reporters she’s been forced to live in a long-term care facility for over 10 years.

Levack said she was only given two options in her early 20s: live at home with your parents, or move into a long-term care facility. That sort of facility doesn’t work for her, she said, because she doesn’t need the same level of care as the other patients.

“I feel the government has robbed me of 10 years of my life,” Levack said.

Levack would prefer to have an apartment where care workers occasionally visit to help her with medication. She said that her solution would actually cost the government less money when housing disabled peoples.

The parents of disabled children who spoke at Wednesday’s news conference all shared similar concerns for the future of their children. They are getting older, and they want to ensure their children are taken care of long after they are no longer able to.

Milt Isaacs, the father of a disabled adult, pleaded with the government to do the “right thing.”

Barb Horner, the mother of a disabled adult, discussed the process of applying for housing placement and funding. She said that for many of the parents in her situation, they have to put their child on a waiting list for help funding their housing and care. In some cases, disabled people have been on the waitlist for over a decade.

Levack said it was important for the government to consult not only with the parents, but with disabled people themselves.

“Please consult us I don’t want my life determined without my consent,” Levack said. “Don’t just talk to the parents. If you talked to my parents they’d say my daughter is 30 years old talk to her.”