Nova Scotia veteran helps provide military burials to service personnel

With the Last Post Fund, Steve St. Amant is making sure veterans are given a proper sendoff

caption

Steve St. Amant stands in the military section of the Fairview Cemetery in Halifax.When Steve St. Amant’s father passed away, the Last Post Fund made sure he got a proper military burial. Now he’s paying it forward.

“I’m helping other families in the same token. That’s important to me,” he said.

In 1908, Arthur Hair, head orderly of the Montreal General Hospital, noticed a blue envelope on a purportedly intoxicated man who had been admitted, the Last Post Fund site reads. The man wasn’t drunk, but malnourished and suffering from hypothermia.

The envelope revealed he was Trooper James Daly, a veteran who had served the British Empire for over 20 years. When he died two days later, his unclaimed remains were to be turned over to science. Hair was appalled by the Empire’s disregard for their veterans and raised money within the community to give Daly a dignified funeral.

This event led to the creation of the Last Post Fund the following year.

Over a century later, people like St. Amant are working hard with the Fund to ensure that fallen veterans are treated with the same dignity and respect. Since the Fund’s inception, they have provided assistance to over 150,000 veterans and their families.

Beginnings

St. Amant’s fascination with cemeteries and military history led him to almost naturally begin volunteering for the Last Post Fund.

As someone who grew up in a military family and served 29 years in the navy, the Armed Forces have always played a central role in St. Amant’s life. Even as a kid, he had a keen interest in the First World War.

He remembers his first time visiting the battlefields in Europe as a teenager.

“Here I am, 15 years old, and I go into the cemetery at Dieppe. I’ve never been an emotional guy, but that hit me hard. I’m looking at these markers, age 17,” he recalled.

On another visit to a cemetery, this time in Ypres, Belgium, in the late 2000s, he noticed a headstone that read “Unknown Officer of the 21st Battalion.” St. Amant found it strange because officers are almost always well-documented. He sent the information back to an expert of the battalion in Canada, who managed to identify the officer.

St. Amant has been volunteering for the Fund officially since 2018, and he is currently vice-president of the Nova Scotia branch.

Unmarked graves

While the Fund provides means-tested financial assistance to help families bury their vets, they also secure gravestones for those who were buried and left without one.

Most people wouldn’t think twice about a gap in a row of gravestones. But for St. Amant, who oversees the Unmarked Graves Program in Nova Scotia, a missing stone is the beginning of an investigation.

He said that gaps are often indicators of an unmarked grave.

While there are many reasons why someone might not receive a gravestone, St. Amant said it’s usually because the family doesn’t have the money to buy one. He says they currently cost about $500 or $600, minimum.

Once St. Amant has identified someone who is buried without a gravestone, usually by checking cemetery records, he needs proof of two things: death and military service. Both of these can be difficult to prove.

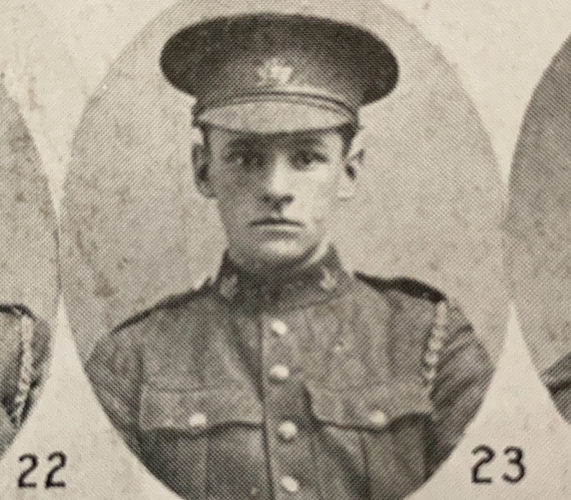

caption

St. Amant is currently working on the case of Pte. Garland Forbes. He was identified in an unmarked grave in the Parrsboro area.St. Amant said that government regulations make it hard to obtain people’s files and information, including documents that prove service and death certificates. He can’t access the death certificates of anyone who has died since 1969, but says that the internet has made it easier to find obituaries and other such records from non-government sources.

Once the evidence is collected, the Last Post Fund sees to the purchase and installation of a military headstone.

Veterans Affairs estimates that there are 2,000 to 3,000 unmarked graves of veterans in Canada, but St. Amant said he believes the number is much, much higher.

“There’s way more. One of our researchers out in Alberta has managed in the past year and a half to locate over 400,” he said.

In 2019, the Fund launched the Indigenous Veterans Initiative that focuses on identifying First Nations veterans and providing gravestones inscribed with their traditional names and tribal emblems.

Pandemic

St. Amant and other Last Post Fund volunteers in Canada have been working from home throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. He says that business has mostly continued as usual. They have continued to process applications and provide families with the resources needed to honour their loved ones.

Still, the pandemic has made it especially hard for those who have lost veterans in their life to grieve, St. Amant said.

“I was a former submarine crewman, and we’re very tight. We’ve had at least three pass on during the pandemic, and there will be no get-together until this crap is over with,” he said.

Correction:

About the author

Jon Werbitt

Jon is a journalist and music enthusiast from Montreal.

R

Robin Wayne

R

Randy Brooks