Off the record

caption

Scott Pyke and Erica Brewster sitting in Pyke's living room.How one Nova Scotian is fighting to change the system, and understand his life

Late one night in his Halifax duplex, off a street where you can see the Dartmouth smokestacks, Scott Pyke opened a door he would never be able to close. Egged on by liquid courage and frustration he joined the Facebook group Adopted in Nova Scotia.

He did not want to be like the others.

“I started reading all these stories where people were trying to find their family members,” Pyke said. “And they were all dead.”

On that December night in 2018, Pyke posted the only information he had: born in Cape Breton, date of birth, and family name.

caption

Almost all of Scott Pyke’s searchng was done on his computer.He also knew his mom was white and his dad was mixed-race. This information was written on his basic records.

That was all he had.

The next month Pyke applied to the Department of Community Services for identifying information, but was given no time frame for when he would receive it.

Searches are done on a first-come, first-served basis. Priority is given to medical emergencies and cases where the birth parents are over 65.

Fifteen months later, Pyke still has not received his records.

After three months of silence Pyke tried a different route. He did the MyHeritage.com free DNA test for adoptees, but it didn’t give him a lot of information. He still posted what he got to online adoption groups, though, hoping they could help.

A few weeks went by and he got nothing, so he decided to pay $129 to Ancestory.com. Six weeks later the results came back – with a solid match.

When he read that someone in the database shared 1,700 DNA sequences he “started to freak out.” Any shared DNA between 1,450 and 2,050 means a grandparent, aunt, uncle or half-sibling. He also discovered what it meant when his basic records said his dad was mixed-raced. His birth dad was black.

caption

Scott Pyke’s Ancestory.com DNA results.Pyke quickly called Teresa MacEachern of Antigonish, who had been helping him search. She enjoys helping families unite, so has made this her hobby. When MacEachern heard the match’s name Pyke received another shock: MacEachern and the match had gone to school together in Antigonish.

“It is you,” MacEachern said.

“What do you mean it is me?”

“You will not believe this; I know people say this all the time. But your family has been looking for you for thirty-plus years.’”

The DNA match was Theresa Brewster, who lives in Cape Breton. Brewster is Pyke’s aunt, his dad’s sister.

After talking to MacEachern Pyke’s emotions were running high. Nervous, excited and scared all at the same time, he called his aunt.

He introduced himself by saying, “I think you know who this is.” She asked his birth date and when he told her, he says, she broke down in tears.

She then asked if he had been okay growing up. After decades of his father’s family not knowing, he put her mind at ease and said that everything was fine, he had had a good home.

They talked for 45 minutes. She got off the line to call his father, also in Cape Breton, and tell him the news.

Secrecy

According to Tarah Brookfield, children who don’t have parents have always needed a place to go. “The solutions in the past were neighbours and kin taking in children, or private charities usually started by faith-based organizations,” said Brookfield, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University. She has expertise in the history of children and youth.

By the late-nineteenth century, she says, countries like Canada “realized children were vulnerable to disease or harm.” Governments wanted children to grow up proper and efficient so “they could be good citizens and not cause any problems.”

This had some negative repercussions. During the 1960s, in what is known as the Sixties Scoop, the Canadian government forcibly took as many as 20,000 Indigenous children from their communities. They were put in foster homes or up for adoption.

Also between 1945 and the early 1970s, according to a Canadian Senate report, mistreated and misinformed mothers were forced to put hundreds of thousands of infants up for adoption.

The Western- and Christian-influenced secrecy still lingering around adoption, Brookfield believes, stems from two assumptions. First, that an adopted child may be dangerous or damaged. And second, that it would be best to give both the child and parents the chance to start anew. So a birth certificate with identifying information was created, and sealed away in government files.

First meeting

Pyke met his birth father, Pat Brewster, for the first time last October, after a wait of 36 years and 10 months. They met at Pyke’s house. He felt he was prepared, and also like the ground was falling out from beneath him.

Pat, who drove down from Cape Breton, was nervous when he came in. Yet he relaxed once they started talking.

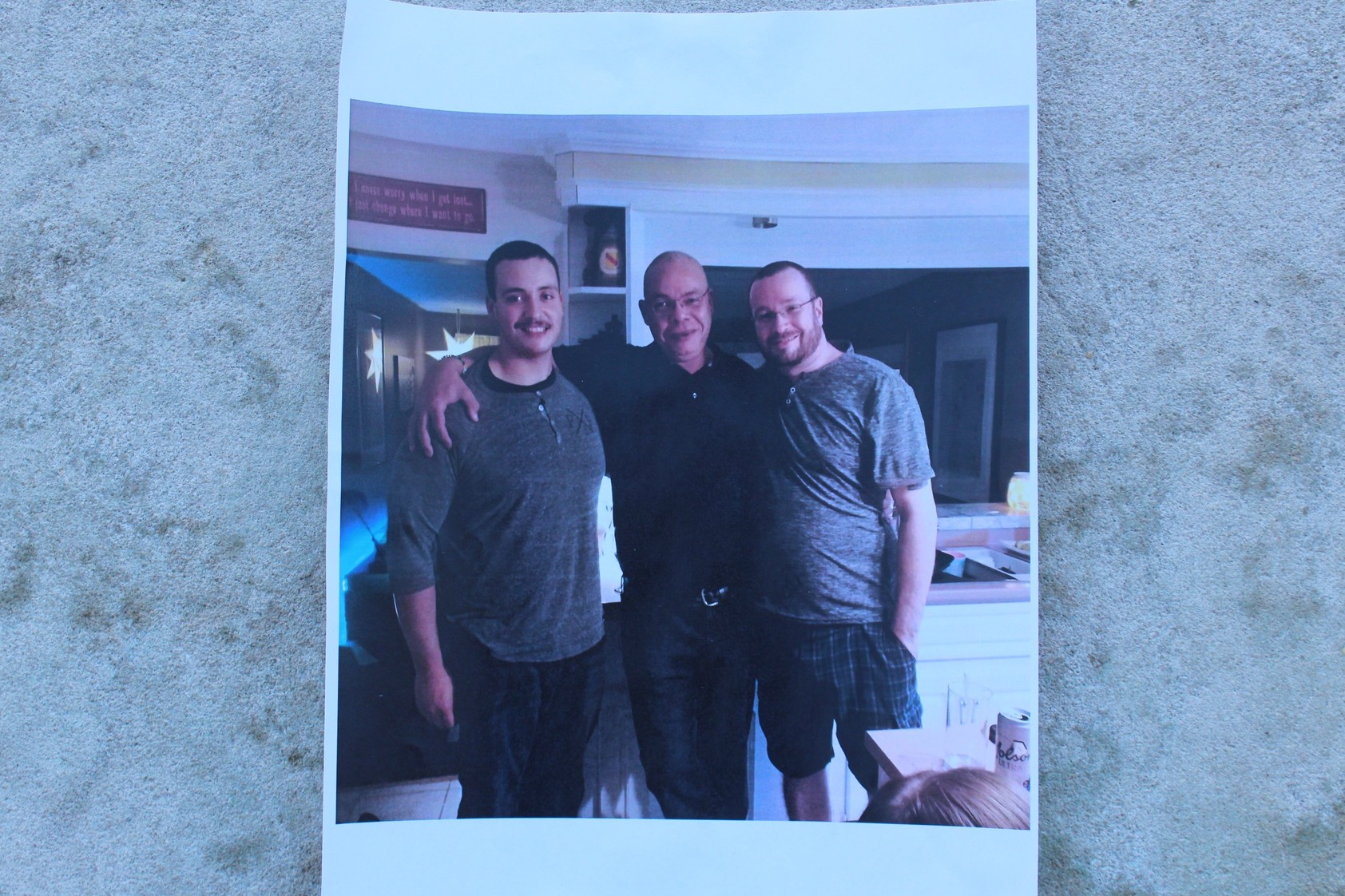

caption

Scott Pyke, his brother Mitchell Brewster (left), and father Pat Brewster (middle).Pyke said there was a lot of regret on Pat’s part. When Pyke was born both parents were just sixteen. Pat knew of the pregnancy, but didn’t know until months later that the baby had been up for adoption.

Pyke understood, and is not angry. It was, he says, the ’80s, and there weren’t a lot of support systems for single parents.

Erica Brewster, a cousin who lives only a short drive away from Pyke, first heard about him when she was twelve – from their grandmother. For years nothing was said about the lost baby. But then Pat moved to Halifax for a time in 2001, and Brewster started babysitting for him.

“He was just sitting there one day, and he was like, ‘yeah, I want to find my son. I have been looking for a while’,” Brewster said. This came after Pat ran into the mother, and she told him that the baby had been adopted in Halifax.

Having Pyke join the family, Brewster says, has been great. “It is the best thing ever. Everyone in our family just embraced him. It is just like: he is my cousin. That’s it.”

caption

Scott Pyke welcomes cousin Erica Brewster into his home.It is not hard to tell that Brewster and Pyke are related. Sitting on a new couch in the living room where his young daughter’s toys lay about, they share stories with the same sense of humour. Both have an inviting and warm way of talking to you, like you too are family.

Pyke also got in touch with his birth mother. They didn’t talk much through the winter, but in March he went up to see her in Cape Breton. They met at a Tim Hortons for a couple of hours. He says it went well, but that relationship is more complicated than the one with Pat. Her side of the family doesn’t know that the mother and son are talking.

Pyke says a lot of reconnections don’t consist of happy tears and long hugs. Instead, some mothers do not want contact. Some fathers don’t either, or don’t even know the adoption happened.

Adoption records

Aiming to improve access to birth records, in February 2019 Pyke created a Facebook group, the Nova Scotia Adoptee Advocacy Group. How long Nova Scotians must wait for identifying information is in part impacted by the province being committed, until recently, to closed records. In March 2020, though, after years of adoption groups pressing for change, the government announced plans to open adoption records by the fall.

Nova Scotia will be the last province to do so.

Currently when people apply for identifying records a Department of Community Services staff member searches for records of the parents or child. If the person is found, the department asks the found person if they consent to contact. If they say no the applicant receives no identifying information.

Pyke assumes that Nova Scotia will soon adopt a method similar to other provinces, in which the government gives birth parents and adoptees a year to submit a disclosure veto and/or a contact preference.

A contact veto is an application in which a person chooses if and how they want to be contacted. Even if they want no contact they can choose to give out identifying information. A disclosure veto, however, ensures no identifying information is released.

Pyke will be fighting to ensure that these privacy measures, and other conditions his advocacy group is lobbying for, make it into the legislation.

“The hope is when they open the records we can say ‘okay, anyone who has put up a kid for adoption between 1940 and now, you need to call and update your medical information, please’,” Pyke said.

His only meeting with one cousin was when that person was on life support following a heart attack. Without meeting the Brewsters, he would never have known that heart attacks run in the family. He never got to know one of his grandmothers, either. She passed away in 2015. These losses made him realize that the process of getting adoption records − simple paperwork − was preventing people from enjoying these kinds of opportunities.

Information like medical records are important, but getting so many kinds of new information can be overwhelming. “No one tells you you are going to have moments where you freak out because it’s just too much to handle all at once.”

There are not a lot of places for people with adoption questions to turn. They often can’t use family and friends for reference, and realistic adoption is not often featured in blockbuster films.

Pyke says he and his partner will marry one day, but they have no idea how to go about the wedding. Where does everyone sit? Who says what? What family members do they invite? How do they make sure not to upset his adoptive parents?

Pyke’s adoption advocacy group will hopefully help people figure these kinds of things out by sharing their own experiences. Another group Pyke belongs to, Adopted in Nova Scotia, will also remain active. But advocacy groups can only do so much. This is why Pyke wants the government to create support systems.

The sad reality, Pyke says, is that a lot of records from the ’40s to the ’80s are missing information.

According to a Toronto Star article from December 2009, when Ontario opened their records in June of that year there were 250,000 adoption registrations. Less than 10 per cent of them included the father’s name.

DNA testing, and people posting information on online groups, will probably only increase. In the seven months that Pyke has been a member of Adopted in Nova Scotia, he says its members have risen from 2,000 to more than 4,000.

Opening adoptions records will give adoptees one piece of the puzzle, Pyke says. To see the whole picture of who they are, other Nova Scotians will need to undergo a journey similar to his – and everything that comes with it, the good, the bad and the ugly.

An abridged form of this story first appeared in the Halifax Chronicle-Herald.

About the author

Olivia Malley

Hailing from Dartmouth Nova Scotia, Olivia is a journalist passionate about the HRM. Outside of reporting she enjoys singing in King's a capella...