One tweet can change your life

caption

The word Cancelled is seen in this photo illustrationHow do newsrooms handle employees being #cancelled?

Emily VanDerWerff never expected her tweet to become an international story. A film and television critic at Vox, she was used to dealing with people on Twitter who didn’t agree with her opinions. On July 7, 2020, she sent a tweet that caused a different level of upset.

“It felt like going through a hurricane,” she said. “Did I really get hit by those 150 m.p.h. winds? I’m fine now. I’m still standing. I’m still around. I didn’t die.”

What did VanDerWerff survive? An attempted “cancellation.”

Harper’s magazine published a letter in July 2020 that called for “justice and open debate.” In short, it wanted to end so-called cancel culture. VanDerWerff took issue with the subtext in the letter, believing it was “telling trans people and people of colour to be quiet.” VanDerWerff noted that if you weren’t in a marginalized community, this subtext would be easy to miss. A journalist who is transgender, she noticed some of the 153 people who signed it were outspokenly transphobic or racist. One of the co-founders and editors of Vox, Matt Yglesias, was also on the list.

She sent a letter to Vox about how she felt seeing Yglesias’ name tied to the letter. She mentioned in her letter, and reiterated throughout her interview, that she never wanted him to face consequences, just to start a conversation.

“It was worth just talking about… what happens when your name gets lumped in with people who have genuinely supported the things that actively made my life more difficult,” she said. She decided to make the conversation public.

VanDerWerff shared her letter on Twitter.

I sent a version of this to the editors of Vox. (I have redacted some bits that are internal to Vox and shouldn’t be aired publicly.) pic.twitter.com/splNNSMivd

— Emily VanDerWerff 🙋♀️ (@emilyvdw) July 7, 2020

What is “cancel culture”?

It’s difficult to pinpoint the creation of the term “cancel culture” to a person. It is credited to Black Twitter, where it emerged as a hashtag around 2016-2017. It was originally used in terms of a cancellation of a contract. If a celebrity made money from having fans, the fans could take that money away by putting pressure on companies that give the celebrity money.

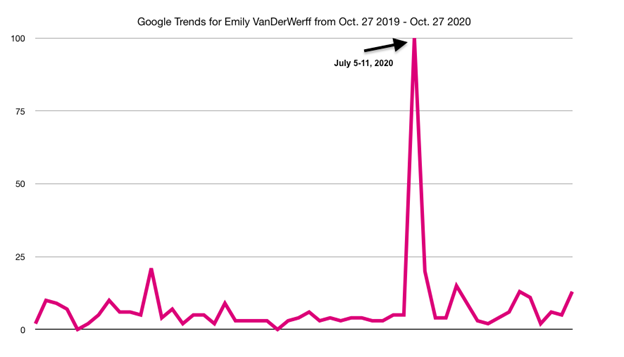

caption

Interest in Emily VanDerWerff over time.The thing that separates cancel culture from traditional forms of justice is that there are no set crimes and no set punishments. The only thing in common is public outrage.

It began as a way for the public to hold people in power accountable. That, historically, has been the job of journalists. So what happens when the journalists are the ones being cancelled?

Emily VanDerWerff’s tweet was online for a few hours before it blew up. She engaged in some debates with people, in what she calls “good faith criticisms.” Jesse Singal, a journalist who signed the original letter, tweeted about VanDerWerff’s response. Singal, a former New York magazine writer, now co-hosts a podcast.

I want to state, again, that I want my colleague to keep his job. I like him personally and appreciate his perspective even when I disagree. My perspective is that he is not shielded from the free speech he champions.

Also, Jesse Singal is an asshole. pic.twitter.com/X2IjKNKjPa

— Emily VanDerWerff 🙋♀️ (@emilyvdw) July 8, 2020

Vanderwerff says Signal’s quote tweet led to it being seen in right-wing media corners of the Internet.

“After that it was really everywhere,” she said, “it was this thing.”

In a Twitter thread during the incident, VanDerWerff said that she was receiving death threats, threats to assault her, misgendering, and “invitations to commit suicide.”

The following is the last thing I will say on this on Twitter: These two days have been hell. Death threats, rape threats, invitations to commit suicide, constant misgendering, etc. On every platform. The only way I can avoid it is to leave the internet entirely. I can’t sleep.

— Emily VanDerWerff 🙋♀️ (@emilyvdw) July 9, 2020

Along with the public tweets, she received a lot of private messages and people sending tweets and deleting them so that she would see them but no one else would. She had to log off for several days.

“A lot of the harassment had nothing to do with what I said and had everything to do with who I am. And that was difficult to bear.”

VanDerWerff remains grateful to her bosses at Vox. The online outlet allowed her to take days off so she could completely unplug.

Vox also pulled some strings to slow the harassment. They called Twitter. After Twitter got involved, VanDerWerff believes the visible abuse dropped by 75 per cent.

In a study by TrollBusters and International Women’s Media Foundation, 90 per cent of women journalists surveyed think that online threats have increased within the last five years. And 78 per cent of female journalists in the US who have been harassed online said that gender was a contributing factor to the abuse.

Even when the right-wing corners of the Internet were calling for her to be fired, Vox stood by her. But when the Internet turns against a journalist for a day, not all of them get to keep their jobs.

Aaron Calvin lost his job from a boomerang of controversy. A reporter for the Des Moines Register, he was working on a profile of local hero Carson King in September 2019. King had recently raised $1 million for an Iowa children’s hospital. Instructed to do a background check by his boss, Calvin discovered King in the past had posted racist tweets. Calvin brought the tweets to King, who held a press conference before the profile was published.

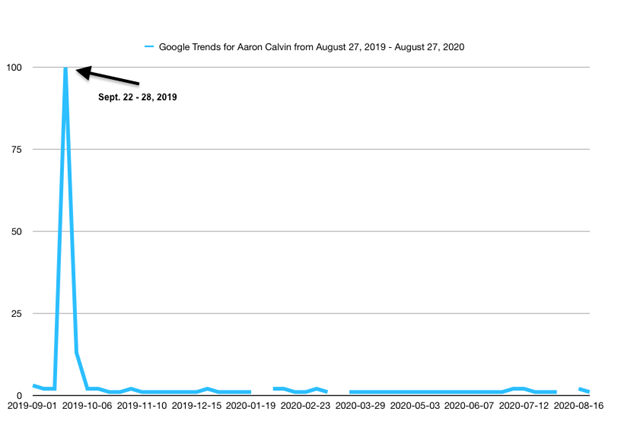

caption

Interest in Aaron Calvin over time.“I was immediately anxious,” Calvin said in an email. He worried that King was trying to paint him and the paper as a “villain.”

Calvin had skeletons in his closet, too. In particular, racist and homophobic tweets from 2010 and 2012. The outrage against him was swift. Calvin stands firm that he never meant to ruin King’s life, and only presented the tweets to show growth. Calvin was threatened, doxxed, and had to speak to police.

The Register gave Calvin the choice to resign or be fired. He resigned.

Why do we cancel?

Shaming people for holding certain views is not new, says Hugh Breakey, president of the Australian Association of Professional and Applied Ethics. He published an article about the Harper’s letter.

Breakey says that shamings have increased due to two reasons: we don’t have to look at the person we are shaming, and social media makes statements more ambiguous.

He says the Harper’s letter was divisive because it only presented one side of a complicated debate. In cancel culture there are no rules about what are considered unacceptable viewpoints. But “we all have our limits,” he says. Until there is an agreement, the discussions will become more volatile.

“When we enter into public deliberation we carry a lot of baggage with us,” Breakey says. Journalists sometimes report information that leads to cancellations, which can put them under the same scrutiny. In the case of Aaron Calvin, the thing he brought to light was the same as his baggage.

After everything, Aaron Calvin doesn’t believe in cancel culture.

“Cancel culture as a concept is almost entirely bogus,” he says. He cites himself as an example of its ineffectiveness. He is still publishing for other outlets, and thinks he is doing “some of the most important work” of his career. He even published an essay about his firing.

VanDerWerff agrees. “It doesn’t exist in the way we think it does,” she says. If the goal of cancel culture is to remove platforms of the cancelled, it is disproportionately silencing marginalized groups.

She points to J.K. Rowling. Rowling had been “cancelled” in June 2020 for defending tweets, deemed transphobic, with a 3,690-word essay explaining her views on biological sex. Yet Rowling is an example of this. She has an estimated net worth of at least $859 million, and published a new book on November 10, 2020.

Even if cancel culture’s validity is under debate, the harassment and online attacks remain undeniable.

“A few people mentioned they felt like the intensity of the discourse on Twitter really accelerated after the 2016 presidential election,” says Mark Lieberman. He is a freelance reporter in Washington, D.C. who wrote a Poynter article on journalists’ growing distaste with Twitter.

He says it is not “cancel culture” but the fear of threats, doxxing, and harassment that makes journalists think before they tweet. Both Lieberman and VanDerWerff emphasized that’s particularly true for journalists who are women, people of colour or LGBTQ+.

Since journalists have larger social media platforms, this puts them at constant risk of harassment. Lieberman said journalists in marginalized groups are “either experiencing that firsthand or having to worry that that will happen to you.”

Courtney Radsch, the advocacy director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, has advice for all journalists to take before they become targets. Make sure all personal information, such as phone numbers or addresses, is hidden from the Internet. This will not prevent harassment, but it will prevent doxxing and lower the risk of online threats moving offline.

“There are relatively few rules that restrict how people can use those platforms,” says Radsch. The CPJ has released guidelines for how to prevent attacks, along with links to help with the trauma that journalists may face from their own “hurricanes.”

Months after the whirlwind of online abuse, Emily VanDerWerff is still feeling the reverberations of what happened to her. She is still publishing her usual two to three articles a week, but says it is taking her longer to write. She unwittingly asks herself a question before she publishes.

“Will this make people mad at me?”

About the author

Emily McRae

Emily McRae is a journalist based out of Halifax, Nova Scotia.