Participatory budgeting: A solution to voter apathy?

Ex-HRM candidate says citizens deserve power over the public purse

caption

Haligonians have been consulted on the municipal budget in the past, but city councillors have sole power to decide where the money is spent.The meeting room in New York City is filled with bright, colourful poster boards displaying statistics, data, and information. People from various ethnicities and community groups bustle around, while the air is filled with the excited chatter of ideas being shared. People engage with one another and show a genuine interest in what’s going on. It’s a Participatory Budget project evaluation, organized by the NYC Civic Engagement Commission.

New Yorkers told city officials the grassroots, interactive budget process empowered them, and provided a way to influence issues that affected them.

In Halifax, a political science professor and former municipal candidate says participatory budgeting worked in New York City and is needed in Nova Scotia’s capital city.

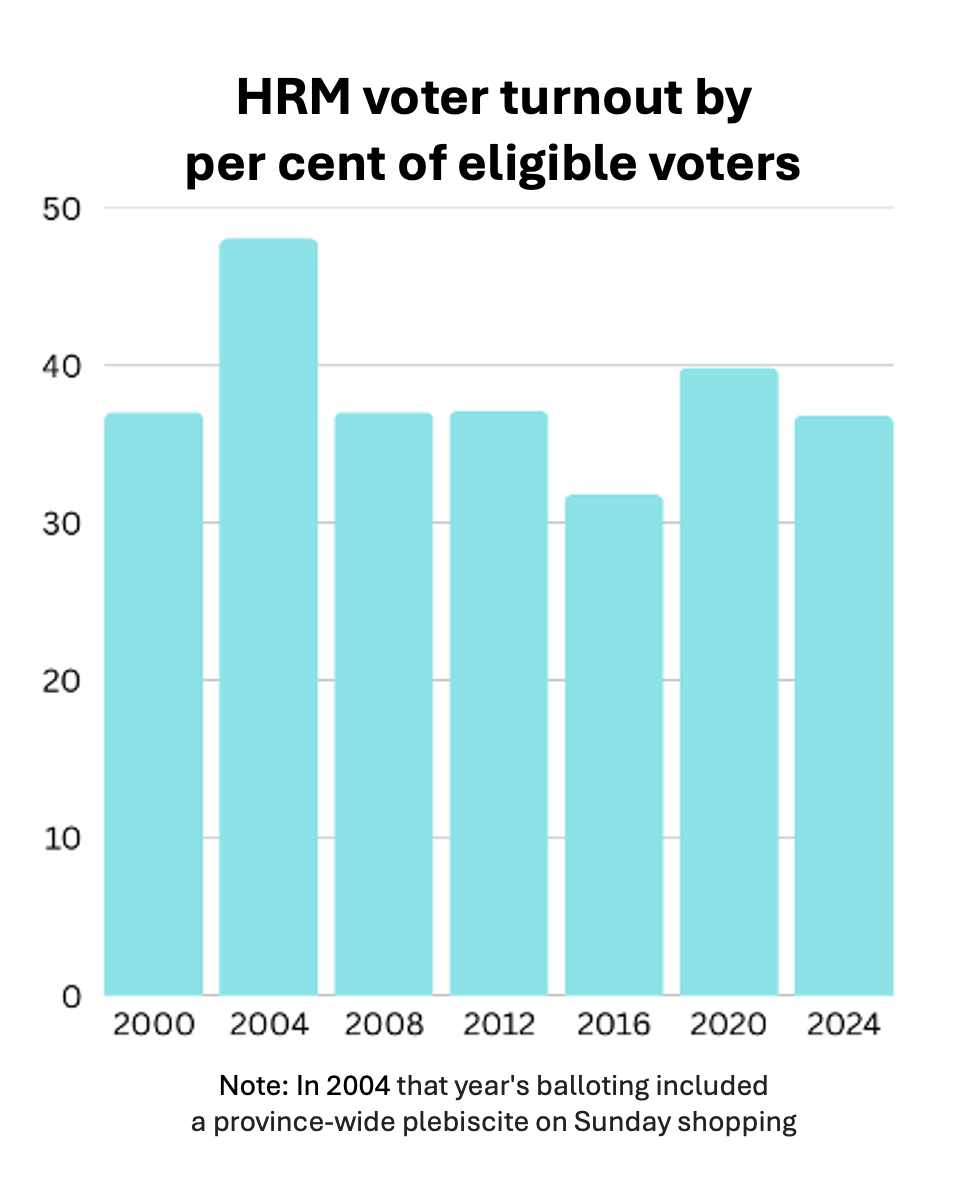

Carlos Pessoa, who teaches at Saint Mary’s University, said participatory budgeting would give citizens a bigger say over public spending in Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM). Participatory budgeting was a part of Pessoa’s campaign platform in the 2024 municipal election, where he finished fourth in his Halifax riding to incumbent Shawn Cleary. Fewer than half of eligible Halifax voters showed up at ballot boxes.

caption

Political scientist Carlos Pessoa ran unsuccessfully for HRM council in 2024 on a platform that included participatory budgeting. He says giving citizens a say in how public funds are spent could help promote greater civic engagement.“I think one of the reasons why (low turnout) happened is because you go, you vote, and then at the end, the politician seems to promise something, then they do something else,” said Pessoa, who specializes in comparative politics. “And that makes you go ‘okay – why should I vote? It doesn’t do anything, right?’”

Pessoa and his parents came to Canada in 1986 from Brazil, where he said participatory budgeting was part of his lived experience.

“A participatory budget is giving the possibility for you to have a voice in where to invest money,” he said. “So that’s a much more direct way. Your participation is not every four years for election, it’s actually every year.”

Participatory Budgeting took root in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989, allowing community members to decide how to allocate part of the budget. The process typically begins with citizens proposing ideas for local projects such as parks, infrastructure, or social services.

New York City, for example, allocated $5 million from the mayoral budget to different boroughs. Borough assembly committees were formed, bringing proposals to the community through town-hall presentations, often with input from experts and government officials. Community members then voted on which projects should be funded.

In 2016 Halifax councillor Shawn Cleary spearheaded a version of participatory budgeting in which local associations could propose, and vote on, community projects before receiving the funding through their district councillor. The initiative faced challenges in 2020 due to COVID-19 and struggled to regain momentum in 2022.

Cleary told The Signal the Halifax version of participatory budgeting has the councillor in charge of organizing where and how funds are spent. He said elected officials must control the purse strings due to HRM’s budgetary policy.

“It wouldn’t be legal for the municipality to provide district capital funds directly to a resident,” Cleary explained. “The funds can only be received by non-profit organizations for eligible projects or be used for municipal infrastructure.”

Cleary did not commit to the New York version of participatory budgeting for Halifax, though he predicted civic engagement would improve if schoolchildren were taught how civic processes work.

“If you’re not teaching people in elementary school, junior high and high school why government is important, you’ll end up eventually getting to where the United States is,” said Cleary, referencing low voter turnout among low-income Americans.

“You end up with a situation where people are apathetic, don’t care, and then you end up with a guy like Donald Trump in the White House, and all of a sudden, you’re like, holy s—.”

caption

HRM municipal clerk Iain MacLean discusses civic engagement with The Signal on Monday, March 3, 2025.Iain MacLean, HRM’s municipal clerk and returning officer, said Haligonians can offer feedback on the city budget after the document has been tabled. However, Maclean added the issue of low voter turnout goes far beyond Halifax.

“I think there’s an inherent issue with participation and people’s willingness to participate in elections across the board,” MacLean told The Signal at Halifax City Hall. When asked why voter turnout was low in Halifax, MacLean replied: “I can’t speak to that from the nature of my position. All I can do is provide the opportunity.”

Pessoa said full participatory budgeting would achieve more than a stronger local democracy – he predicted it would build community.

“We are busy working to pay our bills,” he said. “We don’t have that moment of community chatter. (Participatory budgeting) allows for that moment where you are with others that perhaps you haven’t even met, right? So, it creates the possibility of awareness of the community needs.”

About the author

V. Patterson

V. Patterson is a 3rd year journalism student.