Plagiarists beware: readers won’t be deceived

caption

Plagiarism chokes the public’s trust in journalists.How the public uses social media and online tools to monitor plagiarism

Your deadline creeps closer with every tick of the clock. You ruffle through your notes one last time, trying to find one stone of information left unturned — nothing. Panic sets in. All you need is a little bit of Wikipedia knowledge. Why not? No one will know. Halfway down the Wiki page you see the perfect paragraph to finish your story. Less than a minute to deadline: no time to reword. Two clicks later — good friends copy and paste — part of the Wiki article is nestled in your copy. Deadline made.

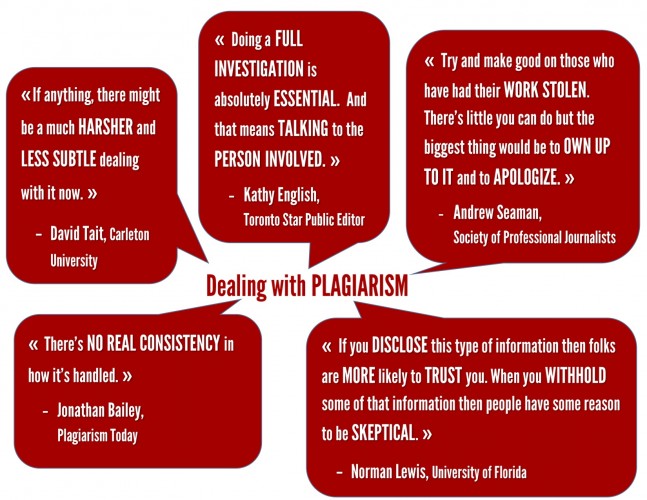

Excuses fly when journalists are accused of plagiarism: sloppy notetaking, being overworked, “I didn’t mean it”, and any variation of these. No matter the excuse, it’s the news outlet’s responsibility to respond to the accusation.

Although news outlets answer to the public, plagiarism cases “have been dealt with very much in-house,” says David Tait, an ethics professor at Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication. “Now, when something is caught, it tends to be caught from outside,” and “broadcast to the world,” he says. “The workplace is responding in real time in a very public way and so they have less wiggle room.”

Tait says social media has created a “lynch mob mentality.” Social media vigilantes, with taut fingers looming over their keyboards, put new pressure on newsrooms. Tait says under this scrutiny many organizations may not “think with very much subtlety. They’ll just try and get the thing off their plate as fast as possible.”

“But I didn’t mean to…”

A lack of consistency in both defining and dealing with plagiarism has led to the sin becoming an ethics Hydra. Just when you think you’ve wrangled one of its issues, two more crop up in its place. And what is seen as plagiarism in one newsroom may just be a shortcut in another.

“Too often the P-word has been used to describe activities that are not serious violations,” says Roy Peter Clark, the Poynter Institute for Media Studies’ vice-president and senior scholar. For Clark, the intent to deceive readers is what separates plagiaristic misdemeanors from felonies.

He says real plagiarism is when “fraud is intended”; sloppy attribution doesn’t fall in that category. At the same time, “I’m reluctant to accept the idea that a writer can unintentionally plagiarize something of any length,” he says. Our Wikipedia thief may not reach fabricator-level pariah, but he’s definitely a close second.

Shauna Snow-Capparelli, media ethics professor and chair of Mount Royal University’s journalism program in Calgary, echoes Clark’s position on intent. “How can you report in the public interest if you have an intent to deceive audiences?,” she asks. “I don’t see how you can.”

Snow-Capparelli was also the Canadian Association of Journalists’ ethics committee chair in 2011 when it updated its Ethics Guidelines. The CAJ’s stance on plagiarism is muddy: “If we borrow a story or even a paragraph from another source we either credit the sources or rewrite it before publication or broadcast.” That sounds fairly simple. But the very next sentence says rewriting isn’t enough. “Using another’s analysis or interpretation may constitute plagiarism, even if the words are rewritten.” Snow-Capparelli says rewriting doesn’t mean just changing a few words. “You have to take it further, with enough original material.”

Norman Lewis, an associate professor at the University of Florida’s Department of Journalism, has published a handful of studies about journalistic plagiarism and totally rejects intent as a worthy argument. “It doesn’t matter whether you meant to or not because the attribution is still missing — and, at a certain level, there’s no way to claim an absence of intent,” he says. “After all, the words didn’t magically write themselves.” For Lewis, the discussion around intent is “a rabbit hole that is both illogical and unfulfilling.”

He says if we focus on intent then we’re missing the point; the real question is, “did it fail to include attribution that would have been helpful to the audience? And if it did, then it’s plagiarism.”

Plagiarism can be used as journalism’s vacuum term for anything that has to do with attribution confusion: from a long-lost footnote to blatant copy and paste. But at its sly, conniving heart plagiarism is taking someone else’s work and presenting it as your own.

Added Production Pressure

It’s no secret: traditional newspapers aren’t the money-makers they once were. In April 2015, the Pew Research Center released its State of the News Media 2015. The Washington, D.C. think tank’s annual report shows a triple threat to traditional newspaper economics: circulation numbers, ad revenue and the number of newsroom employees are all plummeting. Meanwhile, the 24-hour news cycle monster demands to be fed more content than ever before.

“There’s definitely a lot of additional stress on your frontline reporter,” says Jonathan Bailey, creator of Plagiarism Today, a New Orleans-based blog dedicated to educating the public about online plagiarism. Bailey says at the beginning of his career as a journalist, he was expected to write three feature-length stories — between 500 and 1,000 words — a week. “That’s nothing today,” he says. “Your average journalist at a newspaper is probably writing three or four a day when you factor in online media, print and everything else they’re doing.” Bailey says that the pressure to produce makes reporters take shortcuts that often hurt the quality of reporting.

Trying to do more with less is one thing; cheating is another. For Lucinda Chodan, the Montreal Gazette’s editor-in-chief, the push for more content has nothing to do with plagiarism. “People may be producing more or different content than ten years ago, but I don’t see how taking somebody else’s work as your own would come into it,” she says. “That would not be a defense if it happened (at the Gazette) today.”

The audience “reaching back”

In 2014, BuzzFeed fired Benny Johnson, one of its most popular writers, after two people known only by their Twitter handles, @blippoblappo and @crushingbort, accused him of plagiarism. Publications including the Washington Post, Politico and Gawker reported that the pair, which created Our Bad Media — a media watchdog blog — had many examples of Johnson plagiarizing from questionable sources like Wikipedia and Yahoo! Answers. That wasn’t the first time a blogger called out a reporter for plagiarism. In 2012, Carol Wainio accused the Globe and Mail’s Margaret Wente of plagiarism in a column she wrote three years earlier. The Globe’s response was lacklustre. Wente defended herself by claiming she was a victim, “a target for people who don’t like what I write.” Sylvia Stead, the newspaper’s public editor, published an article reducing Wainio to “an anonymous blogger” and the accusations to having “some truth”.

The result? An editor’s note was added to the electronic archive. Many journalists thought the newspaper was trying to protect its prized columnist.

Earlier in 2012, the public played a large part in journalism-wonderkid Jonah Lehrer’s demise. Lehrer was a rising star in science journalism; his pieces appeared in publications including the Wall Street Journal and the New Yorker. “His downfall was sort of crowdsourced,” says Andrew Seaman, a reporter for Reuters based in New York City. Once Lehrer was outed for self-plagiarism, Seaman says the public started keeping a close eye on him. This scrutiny led to Lehrer being exposed for fabricating Bob Dylan quotes in his book Imagine: How Creativity Works.

Seaman, who is also the Society of Professional Journalists’ ethics committee chair, says Twitter has changed how plagiarism is handled. “The process has turned into something that used to take two to three weeks to really investigate to sort of a trial by a jury of the most unforgiving peers you could imagine.” He says any newsroom could use the mob to its advantage. “If you can corral the mob of Twitter and social media into doing good (…) you can use them almost as your investigators.”

Jonathan Bailey, of Plagiarism Today, also sees the potential in using the crowd. “It happened in Germany for politicians, not journalists,” he says. In 2013, PolitiFact reported that during Germany’s election two magazines set up fact-checking websites. Faktomat (by the magazine Die Zeit) was an interactive site where readers voted on which politicians’ statements should be fact-checked. The second magazine, Der Spiegel, one of the most widely-circulated magazines in Germany, created Munchausen-Check and rated politicians’ statements on a “six-point scale for truthfulness.”

“That type of presence can be very, very valuable if done well,” says Bailey. “But, it takes a very dedicated person to pull that off.” But the fickle nature of the crowd usually means it’ll release the alleged plagiarist from its grip prematurely or jump the gun and become premature prosecutors.

So what’s caused the public’s evolution in detecting plagiarism? For one, major publications have been hard-headed, says Bailey, and have “refused or declined or been unable to apply the tools and apply the technology,” to catch plagiarists. Those same tools — plagiarism-detection software and even just Google — are being used more often by audiences who have started “reaching back,” he says. “It’s actually not just Twitter. Wikis are being used to do the analysis and (readers) then use a medium like BlogSpot to publish them, and then Twitter to apply the pressure. It’s social media Yahtzee here!”

Norman Lewis, of the University of Florida, says these public plagiarism investigations are fueled by different motivations. “Perhaps (readers) have been victimized or perhaps they sense something is amiss,” he says. No matter the reason, “an element of the Internet has been used for identification and shaming of perpetrators.”

Responding to lapses

More tools used by a media-savvy audience unafraid to apply pressure on any newsroom: this is the blueprint for a plagiarist-catching machine.

What to do once you have caught one?

“It’s one of those things where we don’t really have a good system to handle (plagiarism),” says Andrew Seaman, the SPJ’s ethics chair. In 2014, the SPJ updated its Code of Ethics and expanded its stance on plagiarism to four words: “Never plagiarize. Always attribute.” The statement leaves little room for ambiguity on what not to do, but there’s nothing about responding to cases or even what makes up plagiarism. Seaman admits the SPJ should develop guidelines, or best practices, to help respond to plagiarism accusations.

The first step: take an accusation seriously. “Doing a full investigation is absolutely essential (…) and that means talking to the person involved,” says Kathy English, the Toronto Star’s public editor. She says she can count on one hand the number of plagiarism cases at the Star that she’s dealt with during her eight years on the job.

[media-credit id=101018 align=”aligncenter” width=”647″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

“All of social media, on any issue, not just plagiarism, has created more potential for a lynch mob piling on of any bad thing,” she English. “What I find quite amazing right now is that the mob won’t settle for anything less than someone losing their job.”

English once received a complaint suggesting a writer had plagiarized from Wikipedia. In her investigation she discovered Wikipedia had actually drawn its information from a story by the reporter. “Accusers of plagiarism aren’t always right,” says English. “I will give every journalist the benefit of the doubt, assuming that no journalist sets out to plagiarize.”

Consistency and transparency, as always, are the key to building trust with readers.

“Especially in mainstream media, the ethics and reputation of publications and reporters is the only thing remotely keeping mainstream journalism afloat,” says Jonathan Bailey, of Plagiarism Today. “When you start damaging the ethics, by any kind of misappropriation, by any kind of theft, it starts eating away at that.”