Health

Portrait of a cystic fibrosis doctor

caption

The life and career of Dr. Terrence Gillespie

In one of the early years of Dr. Terrence Gillespie’s career a fellow pediatrician asked him why he even bothered caring for children with cystic fibrosis.

“What are you treating this disease for? These kids are going to die. Why spend all this money when these kids are going to die?”

It was the late 1960s, less than 30 years since CF had been given a name and proper description. The disease itself wasn’t new — references to sickly children with salty skin believed to be cursed and unlikely to survive appear in medical textbooks as early as 1595.

There is even an old adage captured in an 18th-century book of German-Swiss children’s songs that warns: “Woe to that child which when kissed on the forehead tastes salty. He is bewitched and soon must die.”

Salty skin is one of the distinguishing features of the disease, which is the most common fatal inherited diseases in North America. A defective gene causes the body to produce thick mucus that chokes the lungs and clogs the digestive system.

In the 1960s, when Gillespie took over the pediatric cystic fibrosis clinic at the IWK hospital in Halifax, children diagnosed with CF rarely lived to see their 10th birthdays. But Gillespie had insight into the future of care for CF patients and knew there was hope.

He told the pediatrician the reason CF research mattered was because CF patients deserved a chance: “This could be your child. This could be anybody’s child.”

In his 26-year medical career, Gillespie arguably set the standard of care for CF care centres across Canada. In his early days as a doctor, conversations about death and dying were commonplace. But Gillespie was a part of the evolution of CF care. As time and treatment progressed, he watched as his patients started to live to be adults.

He quickly developed a reputation for being an empathetic doctor who devoted endless hours to the care of his patients, rushing back to the hospital after hours to check on patients, spending hours at a child’s bedside, just to keep them company or make them laugh.

“Whenever there was a need, the nurses were to call him and he would show up. It didn’t matter what hour of the day or night it was, and he would come in,” said CF nurse co-ordinator Paula Barrett, who worked with Gillespie in the later years of his career.

“Whenever there was a need, the nurses were to call him and he would show up.”

Paula Barrett

Gillespie is now 89 years old and has been retired for nearly as long as he practised medicine. In a room in his Halifax home — just a short walk from the IWK hospital — he still keeps stacks of old paper documents from his days treating CF patients. Despite being in the early stages of Alzheimer’s and losing his eyesight, when he pours over the records, the stories behind the names come to life again.

The names of a North Sydney, N.S., family catch his eye and he remembers the mother, a coal miner’s wife. All of her five children were diagnosed with the fatal genetic disease. Gillespie says he only knew two of them — the last two.

“[The older daughter] was the first patient I had who died here; she was a very sick little girl,” he remembered.

She died in September 1967, just one year after Gillespie took over the CF clinic. Her younger sister lived to be 15.

“She was in high school and I remember the mother crying and I asked, ‘what’s wrong,’” he asked the grieving mother. “She said, ‘I’m so happy. She was my first child that ever got to go to school.”

Early years

Gillespie got into medicine a little later in life. He went to medical school at Dalhousie University but took a five-year detour into the air force to help pay his tuition. He returned to Halifax in 1960 as a resident in pediatrics at the IWK under Dr. William Cochrane, who two years before established the second pediatric CF clinic in Canada.

As his residency neared its end, Gillespie started to apply for post-grad fellowships, thinking he would specialize in immunology or hematology. His path changed when he went to Cochrane’s office to talk about a post-grad opportunities in New York. Then Cochrane slid a letter across the table.

“And even before I sat down he just reached on his desk and he handed me a letter,” Gillespie said.

The letter was addressed to every other head of pediatrics in Canada, from Dr. LeRoy Matthews in Cleveland. The American doctor was looking for Canadian physicians to come to Ohio and train in children’s chest disease, particularly CF.

Gillespie’s first instinct was to dismiss the letter. He told Cochrane it “wasn’t his bag,” and he wanted to study in New York. At his mentor’s urging, he eventually relented and went to Cleveland to see what Matthews had to offer.

“In the two years I was in Cleveland, I saw six patients die out of over 300 patients they had seen. In Halifax, I had seen six patients, five of them died.” Dr. Gillespie

In his final days of his residency before leaving for Cleveland, Gillespie spent the night at the bedside of a four-year-old girl with CF in the final stages of respiratory failure. He remembers it was just the two of them.

“I stayed up all night with her, just alone. The child was dying,” he said. “There was nobody there for her.”

Gillespie didn’t know much about the disease at that time, but sat with the girl until she died just before 5 a.m. He phoned Cochrane who met him for breakfast in the hospital cafeteria and they talked about CF and the progressive work Matthews was doing in Cleveland.

“He said, ‘[Matthews] has been called a fake, a liar, a freak, a quack, every derogatory of misfitting name that you can possibly imagine. I’ve heard about this man, but they’ve got him all wrong.’”

Cochrane was eager to mimic the success of the Cleveland clinic for pediatric CF patients in the Maritimes. He wanted Gillespie to learn their methods.

Gillespie spent two years learning from Matthews, whose clinic boasted the best survival rates in North America. His methods were simple: every patient started a full course of treatment in hospital from the first day of diagnosis and then seen every six weeks in clinic. The team knew from the outset that CF children’s lung function would inevitably plummet and adopted an aggressive approach to respiratory treatment.

“In the two years I was in Cleveland, I saw six patients die out of over 300 patients they had seen. In Halifax, I had seen six patients — five of them died,” he said.

In July 1966, after two years in Cleveland, Gillespie returned to the IWK in Halifax. Soon after, he went to the CF clinic with Cochrane and followed as the head of the clinic saw his patients.

“I didn’t say boo, but the wheels were going around in my head saying, ‘I’m going to change that and that and that,” he said.

To Gillespie, seeing success in the care of CF children in the Maritimes meant implementing everything he learned from Matthews in Cleveland. He didn’t realize it at the time, but Cochrane had hand-picked him to take over the CF clinic.

“When we left clinic that morning, he turned to me and said, ‘OK Terry, it’s your baby,’” Gillespie said. “And he turned around and walked down the hall and he never said another word to me.”

Care and compassion

Gillespie spent the next 26 years treating children with cystic fibrosis. Along with the Halifax clinic, he set up a clinic in P.E.I., where he would travel several times a year to treat children on the Island.

“I set [the clinic] up like I did in Cleveland and we got the same type of results. All of a sudden survival went straight up” Gillespie said.

Gillespie knew early diagnosis was crucial in CF, so in the first year that he took over the clinic, he told the head of the hospital about something he had seen in Cleveland, the simple test used to diagnose kids with CF — the sweat test. With one phone call, Gillespie had his test and he emphasized its importance to the young doctors training at the hospital.

“Any damn time at admission rounds there was a kid that could have anything that looked like cystic fibrosis, I would ask about the results of the sweat test, just to make the point about this,” he said.

Soon after he helped to establish the first pediatric pulmonary function lab at the IWK so the clinic could better monitor the lung function of its patients.

“I had a battle royale with the government to pay for the tests, which they wouldn’t do,” he said. “They would pay for the old geezers with chronic obstructive lung disease fine. They didn’t pay for the children.”

Once again, Gillespie took up the fight for something that would help improve the lives of his patients. He eventually got his way and took up a new battle — fighting the government once again to ensure CF drugs were covered under the provincial health-care system. In the end, a law was passed that CF drugs and equipment would be covered for patients and families.

“Families need to know that their CF physician is battling along with them, that they are not alone.”

Dr. Mark Montgomery

In his first 10 years at the helm of the clinic, with the exception of one baby only diagnosed after death, Gillespie saw no deaths among newly diagnosed patients in his care.

“That revolutionized the whole attitude towards CF,” he said.

Through Gillespie’s methods and as treatments continued to evolve and improve, life expectancy among CF patients in Atlantic Canada started to climb. By 1966, about one-third of CF patients at the clinic were over 10 and eight years later, seven of the 76 patients were in their 20s.

Paula Barrett still works as the nurse co-ordinator for the IWK pediatric CF clinic, which carries on Gillespie’s legacy by consistently ranking in the top five of Canada’s 42 CF clinics, and as the top clinic for lung function. Barrett said despite being retired, Gillespie still periodically checks in to see how his now-adult patients are doing.

“He loved the kids and the families and he fought for the kids to get good care in here,” Barrett said. “He just was very dedicated, would come in whenever and stay for how long they wanted. He was known for just spending hours with families, whatever they needed to sort of to help out with the situation.”

Patients would often come to Halifax from across the Maritimes, often without so much as a referral to see him.

On one particular occasion, a mother from New Brunswick arrived in Halifax with five kids — believed to all have CF — to see Gillespie. Gillespie met them at the bus stop to give them a ride to the hospital, where he gathered some money from nurses to be able to feed the family dinner.

Gillespie’s tireless compassion for his patients is something that sticks with Dr. Mark Montgomery, more than 30 years after he trained at the IWK.

“Dr. Gillespie demonstrated the commitment required to assist families in CF care. He highlighted the importance of knowing each person with CF, and knowing their family and resources,” Montgomery said. Montgomery went on to become the director of the pediatric CF clinic in Calgary.

Montgomery says he remembers his mentor as a steadfast advocate for CF who was continuously trying new approaches and thinking about how to improve the lives of people with CF, never settling for less.

“His greatest legacy is to demonstrate to young physicians that CF care is both professional and personal, and that families need to know that their CF physician is battling along with them, that they are not alone, but they have an advocate and an encourager and an expert right there with them throughout all that life has to throw their way,” he said.

When a new diagnosis was made, Gillespie made a point to sit down with the family, spending hours answering any questions they might have about the disease.

“We’d take a few cigarettes, coffee, usually in a classroom and we just talked, not a lecture on cystic fibrosis. I would ask them, what were you told about this disease? What do you know about it?” Gillespie said. “And you talk English, you don’t talk medicine, so people understand.”

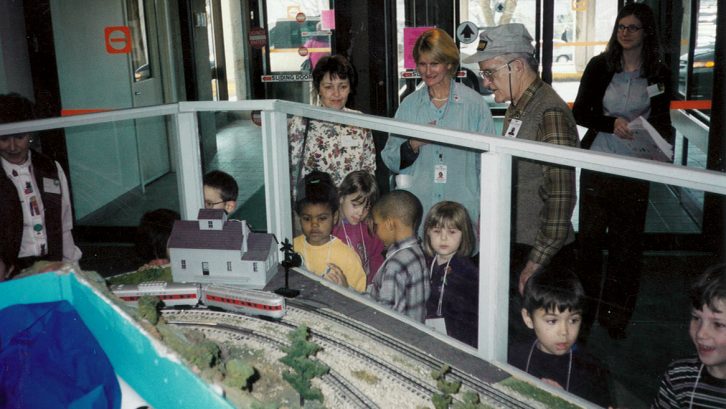

caption

The model trains at the IWK were one of Dr. Gillespie’s passion projects.In 1977, Donna Thompson and her husband sat down with Gillespie. Her two children had been diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. Her four-month-old daughter Jane was hospitalized with a collapsed lung and was incredibly sick.

Thompson and her husband had been planning to go away on a trip, which they started to cancel once their daughter was diagnosed, but Gillespie found out and urged the couple to still go.

“He made a beeline for us,” Thompson said. “He said, ‘You are not to cancel that trip. You need the trip. That’s the most important thing that you can do right now for your children so that you have to be in good shape to deal with this.’”

That intuitiveness from Gillespie was “a gift” that Thompson said reassured her their children would grow up to lead normal lives.

“It would be very easy to give up everything in life and think there is nothing in life but masks and physio and pills, but he was, ‘No, this is how you’re going to learn to live with this disease and you’re going to live like normal people.’”

‘Makes life worthwhile’

I n 1992, after more than a quarter century treating patients, Gillespie was 64, tired and ready to retire. His wife, Rose, saw him working day and night and knew he couldn’t go on much longer. He would spend days at the hospital, come home for dinner and go back at night, constantly on-call and ready to leap whenever the phone rang and a patient or their family needed him.

But despite no longer having a medical licence, Gillespie could never fully remove himself from the lives of CF patients. He kept in touch with staff and families, always keen to know the status of his former patients. In turn, former patients, co-workers and families worked tirelessly to have him admitted to the Order of Canada in 2008.

Gillespie says he has never stopped believing that someday a cure for CF would be found. Medical technology is getting closer with the recent invention of two miracle drugs that target the underlying cause of CF. Today, the median survival age of people with CF in Canada is one of the highest in the world at over 50 years old, and continues to rise.

“I look back on my career and I enjoyed medicine,” Gillespie said.

“You have the satisfaction of knowing, if I do this properly and got those results, I think hey, that makes life worthwhile. And I enjoy that.”

Correction:

About the author

Carly Stagg

Carly is a journalist who has worked in newsrooms in Alberta, Ontario, Nova Scotia and Hawaii. She currently works at CBC News while finishing...

S

Susan (Baker) Coulter

D

Dorothy Vallillee