Possible changes being made to medically assisted death laws in Canada

Nova Scotians have one more week to weigh in on MAID laws in Canada

caption

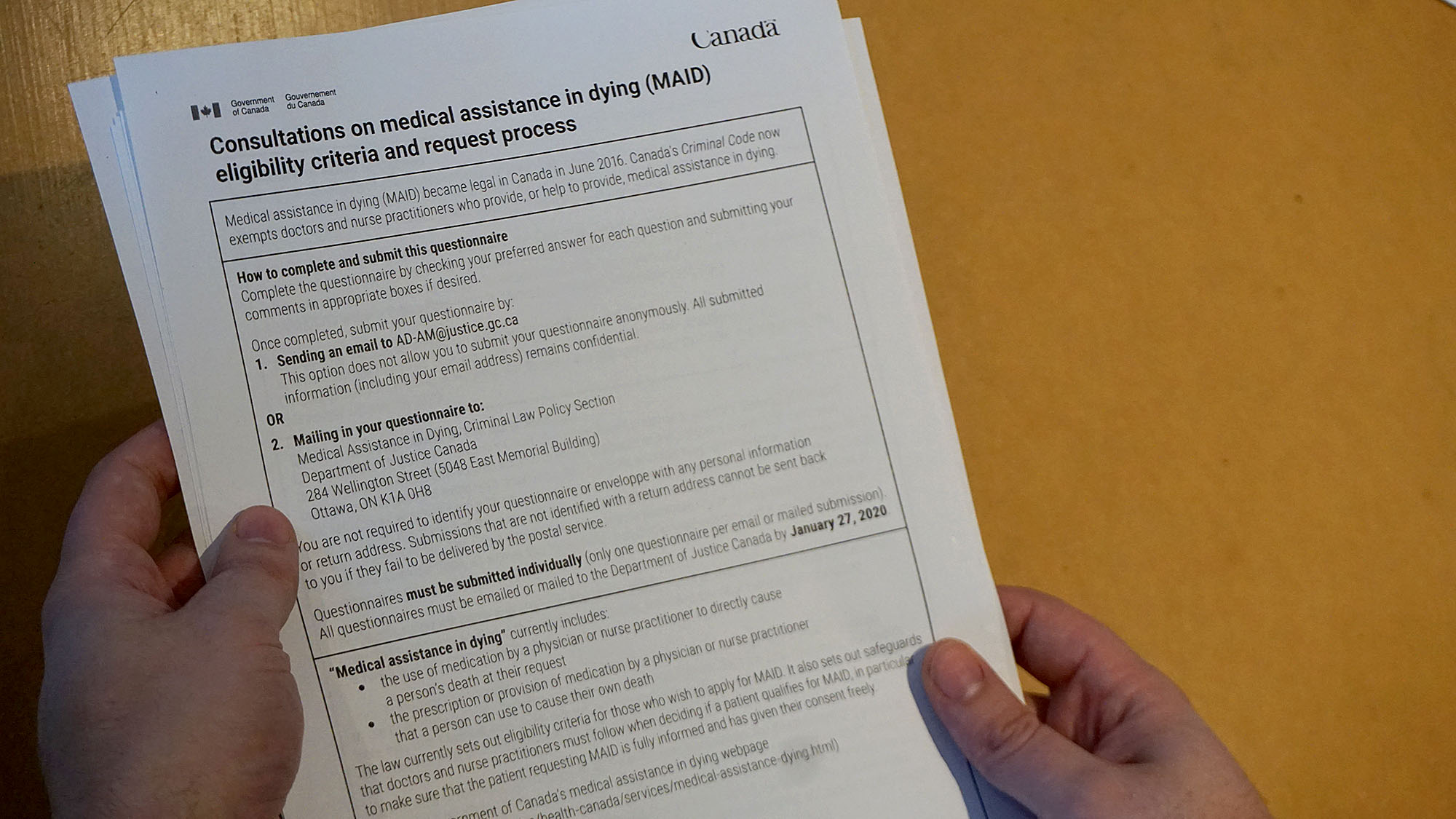

A new questionnaire about medically assisted death laws is open to all Canadians until Jan. 27.A woman living in Dartmouth, N.S., hopes potential changes to Canada’s medical assistance in dying (MAID) laws will address a gap in who is able to access it.

Jude Skaling’s husband was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia in January 2018. Over the past two years, she has watched the disease slowly diminish his quality of life.

Under current legislation, he can’t access his right to a medically assisted death. But Skaling hopes that might change if enough Canadians voice their concerns about the current MAID laws.

“I just feel like we should have that right anytime if we decide that our quality is not good.”

The federal government recently created a questionnaire open to all Canadians until Jan. 27 at 11:59 p.m. The survey will allow Canadians to share their views on this issue.

“Medical assistance in dying is a profoundly complex and personal issue for many Canadians across the country,” said David Lametti, minister of justice and Canada’s attorney general, in a news release.

“It touches people and families facing some of the most difficult and painful times in their lives.”

Lametti said the federal government is committed to updating Canada’s MAID legislation.

“We have a responsibility to do this in a way that is compassionate, balanced, and reflects Canadians’ views on this important issue.”

In the same news release, Health Minister Patty Hajdu encouraged Canadians to participate in the questionnaire so the government “can proceed with the safety and autonomy of Canadians at the centre of our work.”

Roadblocks for dementia patients

MAID became legal in June 2016. According to a report conducted by the federal government, there have been more than 6,700 medically assisted deaths in Canada since it became legal. A report from the Nova Scotia Health Authority shows 251 of these medically assisted deaths were in Nova Scotia.

In September 2019, the Superior Court of Quebec ruled that it was unconstitutional to limit medically assisted death to those who are nearing the end of their life.

In the questionnaire, the federal government stated that “while this ruling only applies in the province of Quebec, the Government of Canada has accepted the ruling and committed to changing the MAID law for the whole country.”

The court’s ruling will come into effect on March 11, 2020.

Changes to MAID laws can’t come fast enough for Skaling, who said her husband’s quality of life is beginning to deteriorate.

With a disease like Lewy body dementia, the lifespan can be anywhere between two to 20 years. Skaling says for her and her husband, it’s more about quality of life than quantity.

“We looked at what his quality of life is and how it’s deteriorating, and do you really want them to live 20 years like that? The answer is no,” said Skaling.

Skaling contacted a lawyer and was immediately told that because of his diagnosis, her husband could not be a candidate for MAID.

“No matter how bad their quality of life gets, they can’t put an end to it and everybody else can,” said Skaling.

Skaling noted two massive roadblocks prevent people with dementia from accessing MAID. Patients need the mental capacity to provide consent immediately before it’s administered, and their death also needs to be considered “reasonably foreseeable.”

With a disease like Lewy body dementia, Skaling’s husband could live for up to 20 years, so his death is not considered imminent. He also may not be of sound mind by the time he would want to access MAID.

‘It’s not fair’

Dr. Marika Warren, a bioethics professor at Dalhousie University, said access to MAID for people with dementia is very dependent on who they speak with.

caption

Dr. Marika Warren reviews the MAID questionnaire.“If you have two people who are similar, and just because of the care providers they have, or the legal experts the consult, they get different answers, and one is able to access MAID and the other isn’t,” Warren said. “That strikes me as being a problem.”

Warren believes there needs to be “a clearer framework to address those sorts of cases and more discussion about how we deal with dementia.”

Skaling hopes the consultation process will get people talking about MAID and the people who are left out of the current legislation.

“I hope that people come forward or at least get the word out that this is happening and it’s not fair,” said Skaling.

“People need to put themselves in our shoes and see just what it’s like, then maybe they would change their mind.”

About the author

Ellen Riopelle

Ellen is a journalist currently living in Halifax. She has a penchant for travelling, hammocks, craft beer and good stories.