Q&A: How Halifax Transit decides bus routes

Explaining the Moving Forward Together Plan

caption

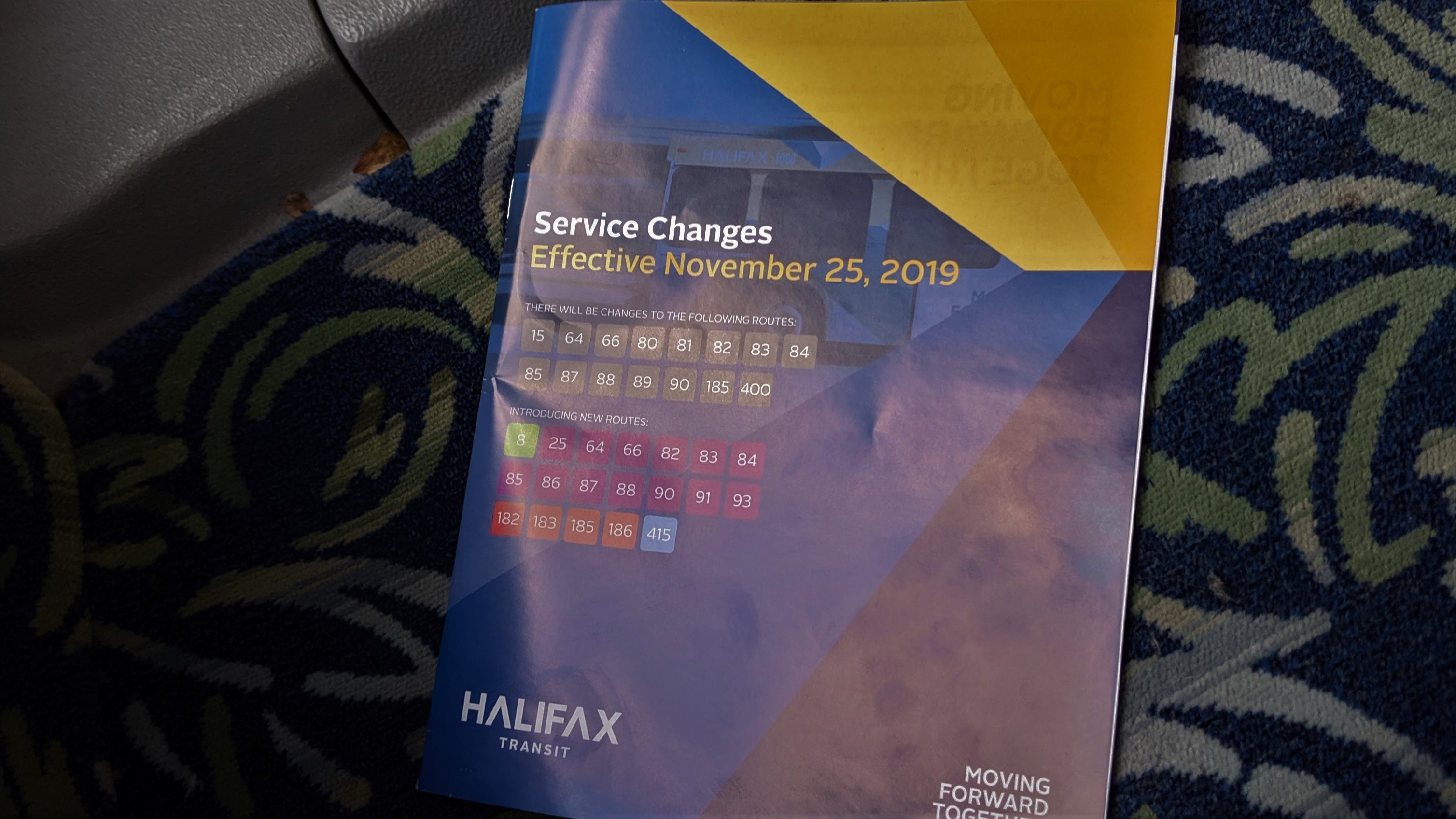

Halifax Transit service changes pamphletThe latest phase of Halifax’s five-year Moving Forward Together Plan takes effect on Nov. 25. This will be the third round of service adjustments of 2019.

Halifax Transit started in 1981 under the name Metro Transit. Many of the routes on the road today are decades-old, from when Dartmouth, Halifax and Beaver Bank had their own transit systems.

The Moving Forward Together Plan was first brought to regional council in early 2013. This plan governs every upcoming transit change. It’s meant to be implemented over five years.

“But then it’s meant to be the base of the network for much longer,” says Patricia Hughes, manager of planning and scheduling for the municipality.

It’s based on four principles: putting more resources toward high-ridership routes, creating a transfer-based system, investing in reliable service and making transit a transportation priority.

The plan lays the blueprint for the minimum ridership level, which is currently 25 people per hour. It also addresses the issue of missed connections, meaning when you have a transfer but your bus gets delayed.

The Signal talked to Hughes about the upcoming changes.

How did the plan come together?

We did workshops and engagement with the public and stakeholders. The questions were about ridership versus coverage: do you put buses where they’ll get the most people, or where they’re needed or else that community won’t have any service? Based on the four principles, we, for the first time in many, many years, started with a blank piece of paper and redrew the network. We took the feedback, which was over 20,000 separate comments from residents, compiled it all, made changes to the network, and produced a final Moving Forward Together Plan. It went to regional council, where it was greatly debated and approved with a couple of tweaks.

What measures is the city taking to ensure the plan holds up over time?

We do have a five-year review plan. Every five years, we would go out and do public consultation and talk about what’s working and what’s not. We anticipate a lot of the future changes will be based on growth and where more service is needed. For instance, the corridor routes (routes that travel between communities) in the plan could definitely use more frequency. But we wouldn’t have the resources to do that as we’re implementing the plan.

How much does public feedback factor into the decision making process?

When the public feedback was contrary to the principles and would take us in a different direction, less weight would have been given to it. Where the public feedback was still consistent and not really detrimental to the network as a whole, then it was considered. For example, we had released that the 1 would no longer go on Bayers Road, it would go on Chebucto Road. The rationale was to reduce the congestion on Bayers Road and to make that service more reliable. We heard a lot from residents on Oxford Street and along Bayers Road through petitions and phone calls and emails. We took another look and agreed the route really should be on Oxford and Bayers, and so we put it back in the plan, subject to “we need to get transit lanes on Bayers Road.”

The plan involves reducing low-ridership routes. What determines a low-ridership route?

We didn’t really set out to cut a lot of service … recognizing that some of our routes are local feeders that have an important role but won’t have high passenger numbers all the time. There’s a lot of ridership standards, so we went with one of the lower ridership standards that would be used.

How do you determine which communities get new routes?

It’s based on population. Washmill Lake Drive, where we put Route 28 last year, is a good example, where we’ve had people calling us for many years asking us to run bus service and asking us when they’d be getting their own bus service. We knew there was a lot of demand and a lot of requests, so it should be incorporated in the new network.

The plan was created in 2015. With each new phase rolled out, is Transit looking at updated data?

Absolutely. As we schedule the new routes, we do it with more accurate runtimes. Every year, when we look ahead to the following year, we’re looking at required frequency, demand, ridership levels and portions of the routes.

How does the plan address the issue of missed connections?

Some of our most chronically late buses are the ones that have really long routes and travel through a lot of municipalities. The transfer-based system helps that. The majority of transfers can happen at the terminal from a local route to a corridor route, or from a corridor route to another corridor route. Part of it is having corridor routes run fairly frequently. If you get into the Dartmouth bridge terminal, and you’re wanting a Route 1 and they’re coming every five or 10 minutes, then the lateness is less of an issue. The other part is that we do know that our most time-sensitive passengers are the ones during rush hours. There definitely is more robust peak express service, that is generally less transfer-reliant for those types of trips.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

About the author

Dominique Amit

Dominique Amit is a journalism student at the University of King's College. She hails from Stellarton, Nova Scotia. She's interested in politics...

Kristin Gardiner

Kristin is a Prince Edward Islander currently working in Halifax. Her journalistic interests lie in copy editing and longform features.