Queer literature for queer liberation

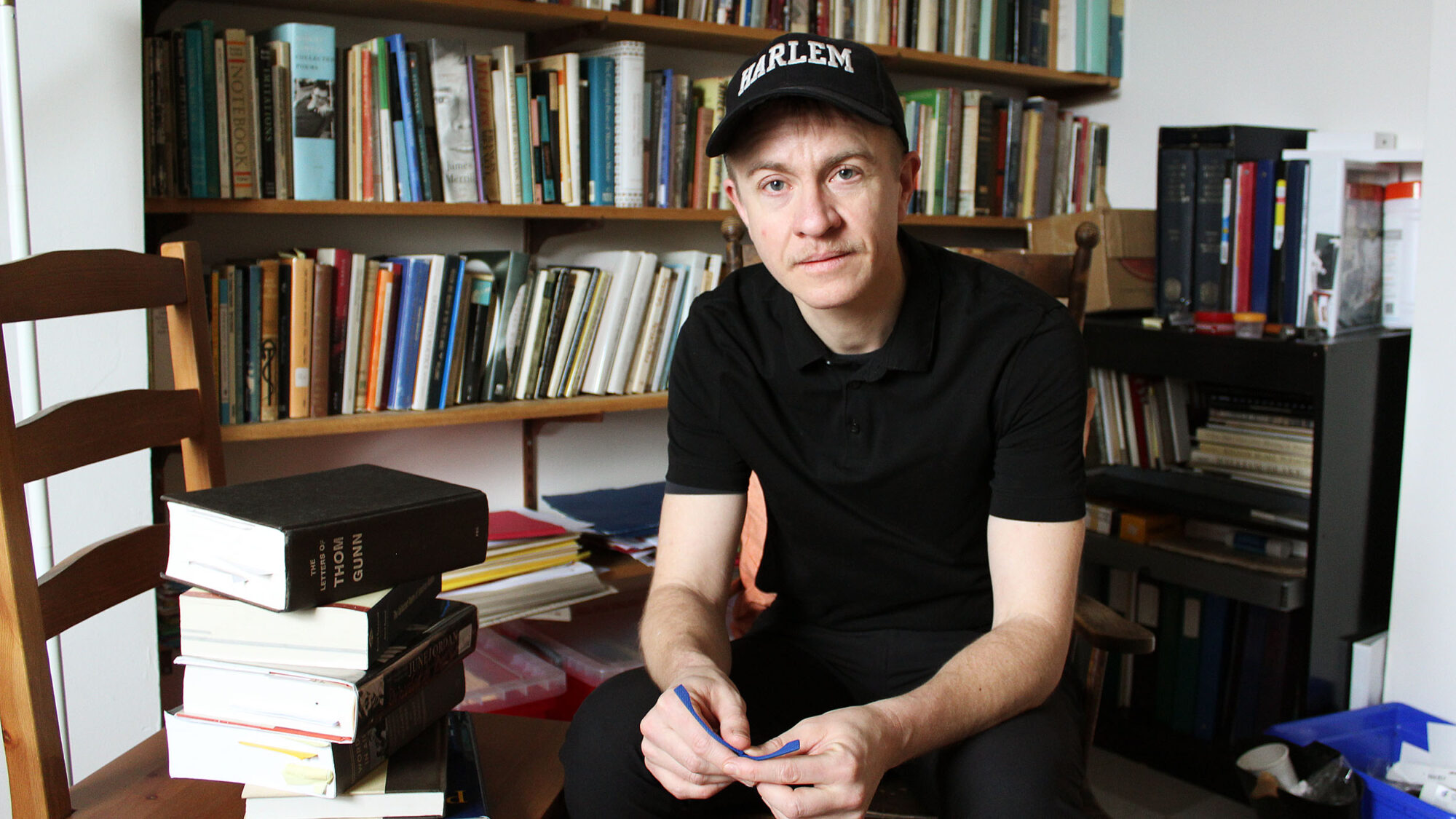

caption

Luke Hathaway has been teaching at Saint Mary's University for five years.A new SMU course aims to empower students at a scary time

On Thursday, January 9, Luke Hathaway was hurrying through the hallways of Saint Mary’s University. Feeling confident in his gold sequin muscle shirt under a sophisticated black blazer, he entered the classroom. This was the first day of the English professor’s new course, Queer Lives & Letters.

Excited but slightly nervous, Hathaway set an armload of books on a table at the front. He quickly scanned the room, one he had not taught in before. There are two doors on either side of the back wall – good. And four windows near the ceiling to his left – nice, but not helpful. He took note of these escape routes. Out as trans for nearly five years, Hathaway is still wary of attacks.

Students were slowly trickling in, making small chatter. Among them was a familiar face, Lucy Pothier-Bogoslowski. Hathaway smiled. Two years ago, this student asked about studying queer literature at SMU. The idea for Queer Lives & Letters was born.

While taking Ancient Literature with Hathaway, Lucy, a keen astrophysics major, wanted more. The prescribed reading and analysis felt strange. They started reading classical texts through their own queer lens. This felt more personal and less distant.

At that time, no SMU courses were dedicated to 2SLGBTQIA+ literature. Hathaway got to work on a new curriculum. Flash forward to January 2025 – 25 students enrolled in Queer Lives & Letters.

Hathaway’s eye shifted to a student who had just burst through the door. They held their arms wide open and offered a wide smile. “Ahh! All my gays are here!”

A strong sense of community was building in the room as the first class got underway. Sharing queer poetry and letters felt like communion.

In the basement of the SMU chapel.

caption

Lucy Pothier-Bogoslowski was the first student to ask about studying queer literature at SMU. Two years later, the course was born.Care for whom?

University is where many people find community and belonging and explore identity during formative years.

For queer folks, finding community can be challenging. During these times of political uncertainty for queer and trans people, the need for community is overwhelming. Especially as Donald Trump’s administration is removing the T and Q of LGBTQ from United States government websites.

When President Trump was elected in November 2024, Hathaway felt like he was sitting under a lead blanket. At the time, he was working on a project with a group of artists – many of whom were queer. The morning after the election, the group was quiet. No one spoke. Panic and dread hung over their heads. Hathaway was grieving the suffering his community was about to endure.

Homophobia and transphobia are being amplified on social media by people in the U.S. and Canada who support the current president. Since the November election, Hathaway says, those voices have been “handed megaphones.” Discrimination against trans people and the 2SLGBTQIA+ community has always been prevalent. Now, the U.S. government, by removing trans identities and language from its policies, is actively pushing transphobia.

Transgender, non-binary, and intersex people in the U.S. have been unable to obtain legal identification with correct names and pronouns. This includes driver’s licences, passports and other government-issued ID.

Within hours of Trump’s first day in office, passport applications allowed only male and female options. Prior to Jan. 20 passports included three options: male, female, and X to represent all other gender non-conforming identities. These changes are erasing trans, non-binary, intersex and gender-nonconforming identities from legal existence.

The Williams Institute of the UCLA School of Law is a leading research centre aimed at improving law and public policy for sexuality and gender identity. Following the executive order titled Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government, which Trump signed on January 20, 2025, Williams released a report to break down the effects of the President’s plans. Millions of people have been targeted. In the U.S., an estimated 1.6 million adults identify as transgender, and 1.2 million adults identify as non-binary or gender nonconforming – ie. not identifying within the female-male gender binary. The same report says an additional five million Americans may be intersex, meaning that many intersex individuals are not medically documented.

caption

The course Queer Lives & Letters considers the community’s strength and vulnerability.Within Canadian borders

Some Canadians might wonder, “but that’s not happening in Canada, so how does it affect us?” The erasure of queer and trans rights in the U.S. has a rippling effect on the queer community in Canada. Queer folks in Canada are horrified for their communities who are suffering across the border and afraid that the same thing could happen here.

If Pierre Poilievre, who has a history of voting against queer and trans rights, wins the upcoming federal election, 2SLGBTQIA+ Canadians could be in danger. Poilievre has been vocal about restricting trans rights and banning trans youth from accessing gender-affirming health care.

In a 2024 report by the federal department of Women and Gender Equality, 4.4 per cent of Canadians above age 15 identified as 2SLGBTQIA+. That is more than 1.3 million people. (And not all queer people publicly disclose this information.)

A survey by Statistics Canada shows 10.5 per cent of the 1.3 million 2SLGBTQIA+ Canadians are between ages 15 and 24. Many of these are university students, which suggests a need for universities to offer courses with 2SLGBTQIA+ material. Dr. Asha Jeffers, a professor of Women and Gender Studies and English at Dalhousie University, says that courses on queer literature are in high demand. She noticed that while many courses incorporate 2SLGBTQIA+ themes and content, not many queer courses are being offered.

More than offering just another literature course, Hathaway’s intention for Queer Lives & Letters was to meet the needs of SMU students in the queer community. Showing up for his students every week was “a vocation of care.” Being an openly trans professor on campus, he says, is a “profession of care.”

“There’s no other class really like it,” said Alex Phillips, one of Hathaway’s students, “where you can talk about queerness in a safe space with other queer people.”

Growing up queer

His parents were from Virginia, but Hathaway grew up in Nithburg, Ontario, west of Kitchener. In a conservative rural town, he had no idea he was queer until his teenage years.

Living as a woman for 40 years, Hathaway struggled to understand his own identity. He now wishes that he’d had a queer mentor in high school. Maybe that is why he became an English professor, to be the mentor he never had.

While he knew he was bisexual, he had never heard of transgender people, let alone met a trans person. Hathaway would not meet a trans woman until his 20s, and then a trans man in his 30s. Only then did he realize that he could live a more authentic life.

During the summer of 2020, Hathaway transitioned from female to male. He had just started teaching English at SMU full-time earlier that year. He worried about having to re-introduce himself to his students with a new name.

To his surprise, his class that summer embraced him as he debuted his newfound identity for the very first time. The students, he said, gave him “a soft landing place.”

caption

These Blundstones, spotted in the classroom, are in tune with the coursework.Growing fears

On a Tuesday afternoon at 2:05, 10 minutes are left in class. The twenty students in the room are asked about their fears for the future. They express worries about their lives, communities, education, families and health. That makes sense; everyone worries about these things. But other fears expressed in the room are not felt by everyone in Canada. Queer Lives & Letters provides, for a few hours a week, a shelter from growing fears. But the fears persist.

The queer community has had legal rights since the 1960s, and in 2005 same-sex marriage was legalized. But students now fear normalized homophobia. They fear hate speech, hate crimes and violence. Just last July a queer couple in downtown Halifax was attacked for walking down the street holding hands.

Will access to basic healthcare be denied based on gender identity or sexuality? Will they be able to receive mental health care? Thankfully, there are health-based resources for queer people in Nova Scotia.Will trans and gender-nonconforming people lose access to gender-affirming care? This includes surgeries, procedures and hormone therapies to which access could be restricted, as is happening in Alabama, Arkansas, Texas and Arizona.

Others, including Hathaway, are worried about visiting loved ones across the border. Some in the class are worried about losing community both in Halifax and on social media such as Instagram and TikTok. They worry aboutlosing online resources, tools and books. The 2SLGBTQIA+ community is worried about losing support from queer allies (non-queer people who support the queer community) and from other 2SLGBTQIA+ people.

There is a fear of losing anonymity, because some people do not want to be out. Other people are afraid of supporting the 2SLGBTQIA+ community without having assumptions made about them. They fear isolation.

The world saw what can come from isolation five years ago when a global pandemic swept the planet. This time, isolation is being created by the U.S government removing the T and Q from LGBTQ documentation and websites.

Isolation is a deadly fate.

Queer liberation

Isolation is sadly familiar to the 2SLGBTQIA+ community. The class has been learning about four prominent queer poets and writers who lived through some of the loneliest times for queer people in the U.S. Among them was Thom Gunn, who lived through the 1980s AIDS crisis.

Sitting on a table, Hathaway began to read aloud Gunn’s poem Lament. In the ’80s, gay men in San Francisco were forced into isolation out of fear of the deadly sickness. Although Gunn made it through, he wrote poems about friends who died of AIDS.

As soon as Hathaway took a breath, the air in the room shifted. Students turned to hear his soft but steady voice.

“Your dying was a difficult enterprise,” he read. Page after page, the poem depicts the friendship between two gay men. The love and heartache of losing a friend.

Even though the students had not lived through the ’80s AIDS crisis, they connected with Gunn’s rawness and vulnerability. The words of the poem danced through the air like the tune of a lullaby. The tone in the room swayed because, despite the tragedy in Gunn’s words, he survived.

This was the very reason for Queer Lives & Letters: to exist as queer people despite the troubles of the world. Despite political and cultural uncertainty. Despite homophobia. Despite isolation. Despite changing laws to erase trans people in the U.S. Despite fears of one day living in a country that diminishes queer existence.

“In hope still, courteous still, but tired and thin,” Hathaway continued to read, “You tried to stay the man that you had been.”

His voice filled the room with comfort.

caption

Hathaway delights in giving Saint Mary’s students a timely and meaningful course.About the author

Laura Flight

Laura Flight is a journalism student at King's. She has a BA in English from MUN and is working towards an MA of Women and Gender Studies at...

L

Luke Hathaway