Traditional Healing

Seven Sparks

caption

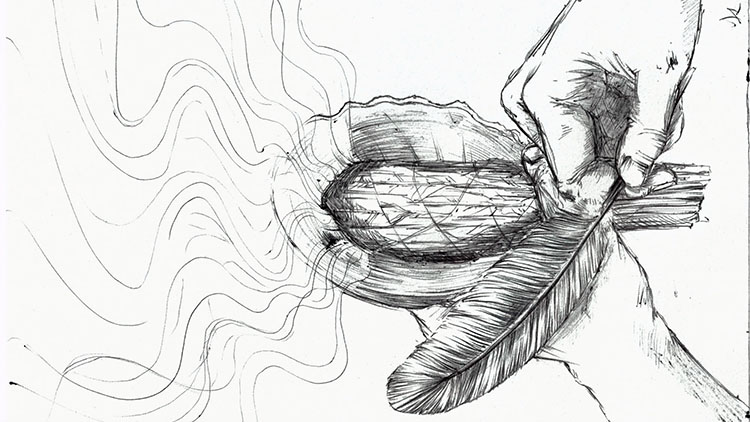

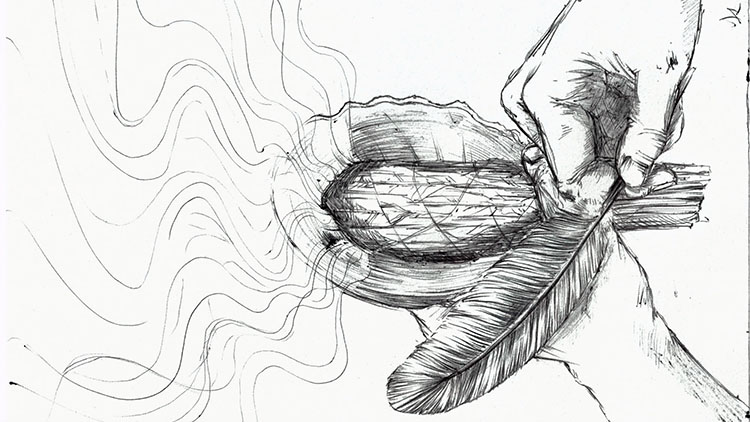

Smudging is a daily ritual. It happens once in the morning to greet the sun and give thanks for the day to come, and again at night to give thanks for the day that has passed, and the night ahead. Four traditional elements are used in smudging; tobacco, cedar, sweet grass and sage.A transition program for Indigenous offenders hits a bump on the red road

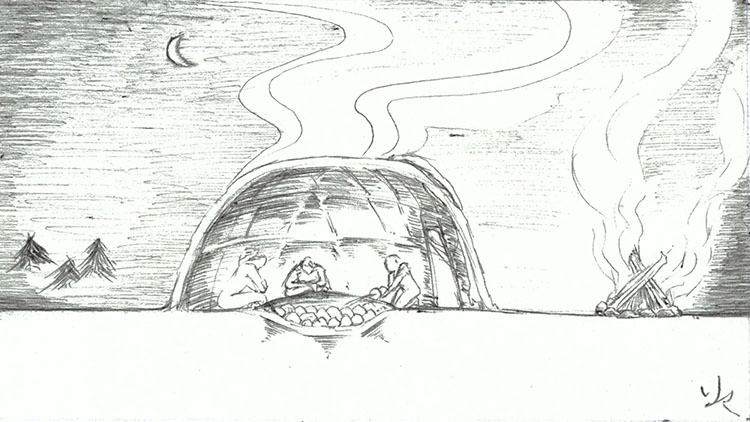

The door of the hut faces east, toward the morning sun. Between the door and the horizon, a fire keeper watches over 40 grandfather rocks heating by the fire. The sweat lodge keeper is the first to enter the hut, followed by the men, crouching low to the ground on their hands and knees.

Ten grandfather rocks are brought in, and placed in the centre of the hut, before the sweat lodge door is sealed. The keeper begins the prayer. He pours water onto the rocks. Steam fills the lodge. A bucket of water is passed around for hydration. Ten more grandfather rocks are brought in, and the prayer begins again.

The sweat lodge is a traditional Indigenous healing practice. It has been a cornerstone of the Seven Sparks program – a program that helps Indigenous inmates and offenders transition from prison life. Participants ask the creator and ancestors to forgive past transgressions through prayer.

“You go in dirty of mind and body, and you come out cleansed,” says Robert, explaining the importance of a “sweat.”

caption

The sweat lodge hut represents Mother Earth’s womb. The sweat from the ceremony symbolizes the wetness on a baby when it’s born.Robert is Mi’kmaw. He has been in and out of prison his entire adult life, mostly on alcohol and drug- related charges. He has asked that his last name be withheld to protect his privacy. He worries that sharing his story will hurt the new life he is trying to build for himself.

That new life means reconnecting with his culture. The sweats helped, but Seven Sparks doesn’t offer them anymore because of programming cuts. It means Robert and other participants are now missing out on a key cultural part of the recovery process.

Seven Sparks

Scott Lekas created Seven Sparks in 2009. The goal was to help Indigenous offenders find their way back to the red road – the traditional Indigenous way of life – by combining cultural practices – smudging and sweat lodges – with employability and other “soft life” skills training such as resume writing and education that are found in mainstream transition programs.

Lekas was program development coordinator at the Mi’kmaw Native Friendship Centre then. He saw that many people wanted to follow the red road, a journey most offenders began in prison, but as a non-Indigenous man he didn’t feel he was the right person to guide them.

He hired elder Emmett Peters to lead the cultural elements of the program. Peters had worked with Indigenous inmates in prisons across Atlantic Canada for decades, and was responsible for introducing sweat lodges to facilities in the region.

“There was a great deal of respect for him,” Lekas says. “He had almost an immaculate bullshit detector.”

The program also included drug, alcohol, and anger management counselling, as well as talking and healing circles, and smudging.

Geri Musqua-LeBlanc understands how following the red road can change an Indigenous offender. She’s seen it work in her own community in western Canada.

“The old life is gone,” says Musqua-LeBlanc, an elder and co-ordinator of the new Elders in Residence program at Dalhousie University.

“A lot of those pretty bad guys that follow the red road are now keepers, which they would have never been before, because you have to be pure of heart to be a keeper.”

caption

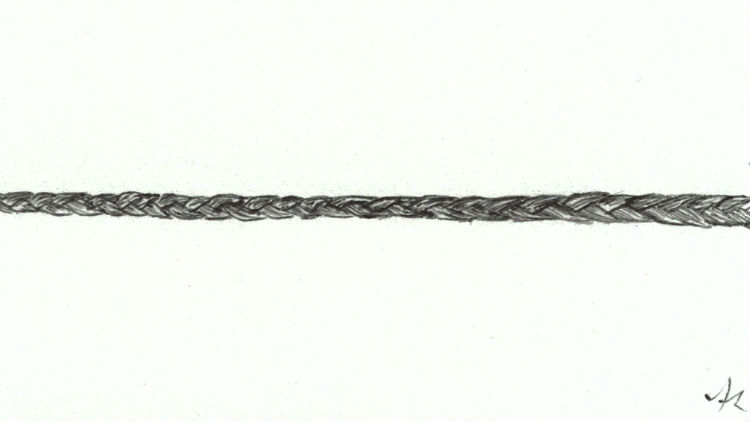

Sweet grass is an Indigenous medicine, thought of as Mother Earth’s hair. The strands of the braid represent spirit, mind and soul.Amy Bombay, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University’s school of nursing, says understanding healing approaches for Indigenous inmates means understanding the role of history, culture and community.

Bombay, who studies intergenerational trauma, notes there are strong links between the residential school experience and being a victim of violence in Indigenous communities today.

She points to a study by James Waldram, a psychology professor at the University of Saskatchewan, that found that Indigenous inmates participated more during counselling sessions that acknowledged historical events than those sessions that didn’t.

“For Aboriginal inmates, to discount the history of their people is to discount them personally,” says Bombay.

Robert has attended both types of counselling programs. He says Seven Sparks helped him “come out of his shell” and change his behaviour. He’s been with the program since the beginning.

“Now when I think about going out drinking and drugging, I stop and ask myself if there is something more social or productive that I can do,” he says.

Robert says he understands now that his alcohol and drug use was a result of suppressing abusive behaviour from childhood. He wonders what his life could have been like if he was able to talk about the abuse sooner.

“The work and the help they do for people is amazing,” says Robert.

Robert’s story is far too common in Canada’s prison system, which has an over representation of Indigenous peoples.

In 2014-15, Indigenous offenders accounted for 25 per cent of inmates in provincial and territorial correctional facilities and 22 per cent in federal institutions, according to Statistics Canada. Indigenous peoples represent only four per cent of Canada’s population.

Seven Sparks 2.0

Seven Sparks hit a bump in 2014. The one-time government grant ended; there was no more money from the Aboriginal Corrections program of the federal Department of Public Safety. A few months later, elder Peters, the heart of Seven Sparks, died from cancer.

The friendship centre stepped in to cover Lekas’ salary — the basic cost of running the program. Lekas says he couldn’t afford to hire an elder to work full time on a shoestring budget.

It meant the loss of virtually all cultural elements from the program.

caption

Smudging happens in the morning to greet the sun and give thanks for the day to come, and again at night to give thanks for the day that has passed and the night ahead. There are four traditional elements: tobacco, cedar, sweet grass and sage.“We got five years of funding, which is almost unheard of,” says Lekas. “It allowed us to grow and really find our feet. But you can’t go back to the well.”

The challenge for Lekas and Seven Sparks is to keep the focus on culture despite funding issues.

Seven Sparks still doesn’t have a set curriculum. Lekas meets with an offender to create a program based on their needs. For some people that means visiting the friendship centre, where the program is based, every day. Others might go to a support circle when they need it, once every three or four weeks.

Lekas is searching for alternative funding. He says part of the challenge is that the program has grown “multi appendages” since it was created to meet the needs of the offenders, and it doesn’t fit into any funding criteria. So far, he’s come up short.

“You have to either craft your language in a way so you kind of fit with somebody, and we’ve been to federal justice, provincial justice all over the place,” Lekas says.

He hasn’t lost hope. Lekas says Seven Sparks aligns with the Canadian government’s mandate and believes the program will find federal funding soon.

He considers Seven Sparks a success. Lekas measures that by determining whether the needs and goals of the participants are met.

“That’s what counts, isn’t it?” Lekas asks. “They want what everyone wants – good job, good relationship, good friends.”

More than 100 people have used Seven Sparks since it began, and Lekas says some of them continue to be connected to the program years later.

Robert, who has come to rely on the program, is grateful it still exists at all.

“You only get out of the program what you put into it,” he says.

About the author

Kathleen Napier

Kathleen Napier is currently completing her Master of Journalism (Data and Investigative) at the University of King’s College in Halifax. Special...