Law

Sexual assault trials often cause ‘further harm to victims’: women’s advocate

Director of sexual assault centre says celebrity trials highlight the lack of support for victims

caption

The Jian Ghomeshi trial began this week and has garnered significant media attention.

caption

The Jian Ghomeshi trial began this week in Toronto and has garnered significant media attention.If you’ve seen a newspaper, listened to the news or even just been alive for the past few days, you probably know the criminal trial of Jian Ghomeshi began this week in Toronto.

While Ghomeshi’s public stature ensures his case will garner significant media coverage, an advocate for victims of sexual assault says “it is not going to be much different from any other sexual assault trial.”

And that’s not necessarily a good thing, she says.

Jackie Stevens, the executive director of the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre in Halifax says legal proceedings often re-victimize those who have suffered an assault.

caption

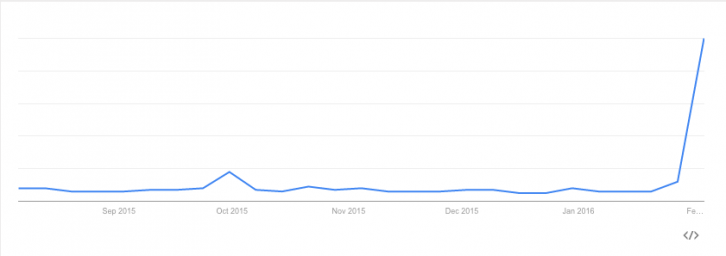

A Google Trends chart showing two spikes in web search interest in “Jian Ghomeshi” over the past six months.Stevens says that while a highly public case like this can help the public better understand the issues, it also highlights “the lack of support and the lack of justice in place for victims.”

After a victim of sexual assault reports a crime to the police, Stevens says the victim loses control, as the decision to charge and pursue a case in court is determined by the authorities.

In the Ghomeshi trial, the credibility of witnesses has already become a relevant factor in casting doubt on the evidence against the accused.

Media reports of the trial have related defence counsel Marie Henein’s efforts to question the alleged victim’s memory of Ghomeshi’s car and whether hair extensions were present during an alleged incident of hair pulling.

To be found guilty of a crime in Canada, the judge or jury must be convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the crime did occur. If there are gaps or inconsistencies in the witness’ recollection of the crime, defence lawyers are obliged to draw the court’s attention to them.

“Attorneys can do their absolute best to prove their clients are innocent without resorting to tactics that cause further harm to victims,” says Stevens. “And yet, a lot of different attorneys continue to use rape myths, gender stereotypes and victim blaming as a way to discredit victims.”

caption

Jackie Stevens says the legal process can often be as traumatizing to a victim as the sexual assault itself.Richard Devlin teaches legal ethics and professional responsibility at the Schulich School of Law at Dalhousie University. He says these types of cases have presented an ethical dilemma for decades.

On the one hand, a defence lawyer is ethically bound to provide a zealous defence in the best interest of their client, but Canadian lawyers are also bound by an ethical duty to act honourably.

Devlin says a test is whether a lawyer’s behaviour brings the administration of justice into disrepute. He says ultimately, it is the shared responsibility of attorneys, prosecutors and judges to ensure that credibility is assessed without re-victimizing the witness.

Because witness credibility is so important in a sexual assault case, Stevens says “a lot of people who commit sexual offences deliberately prey on people who are vulnerable, who are less likely to be believed.”

While the justice system works to ensure the accused is presumed innocent and given a fair trial, she says a witness may feel discredited or blamed after testifying.

“Sometimes, going through the legal process after sexual assault can be just as traumatizing as the sexual assault itself,” says Stevens.