Small-town living. Big-city prices. A crisis of affordability

Hot housing markets and short-term rentals once only affected metropolitan areas. Now, they are threatening rural towns across Canada.

Located on Lake Ontario’s northern shore between Toronto and Kingston, Prince Edward County could be cut from a postcard. Boasting a thriving wine industry, a vibrant arts and culture scene, sandy beaches, and even a provincial park, the county is one of Ontario’s gems.

Prince Edward County, like many small communities in Canada, has become a prime pandemic destination for people looking to leave big cities behind — but only if you can afford it.

“We are in crisis mode,” said Charles Dowdall, executive director of the Prince Edward County Affordable Housing Corporation. “In the last 18 months, the average house price in Prince Edward County has increased 94.6 per cent.”

The rental market in the county has followed suit. The average rent for a bachelor apartment is $1,078, one-bedroom apartments are renting at $1,456, and two-bedroom apartments average $1,817, not including utilities.

These prices aren’t much lower than what you would see in Toronto and Montreal.

“The numbers are absolutely staggering,” said Dowdall.

caption

Charles DowdallPrince Edward County is just one community out of hundreds across the country struggling to provide adequate housing for Canadians, and the reasons are complicated.

Canada has been grappling with two separate but related crises for the past two years: COVID-19 and affordable housing. Even before stay-at-home orders had brought many lives to a halt, record numbers of Canadians were leaving the country’s biggest cities in search of more affordable homes. Those who could work from home were now living in their offices. Many Canadians who had planned on downsizing or moving to different towns in a few years took the pandemic as a sign to start packing. According to Statistics Canada, the three largest cities (Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver) lost more than 87,000 residents between July 2019 and July 2020.

A wave of new residents has crashed onto the banks of Prince Edward County. People who once toured the county on vacation decided they could move there and enjoy all the benefits year round. This exodus runs counter to the trope of the upwardly mobile leaving cozy small towns behind for the opportunity of busier metropolitan cities. Small towns have long been a haven to those seeking quieter neighbourhoods, closer-knit communities, and a better connection with nature. Above all, rural towns have historically been cheaper places to live.

“I see the pandemic as a kind of natural experiment where individuals were more or less forced to make changes and think differently about where they live,” said Michael Haan, the Director of the Statistics Canada Research Centre at Western University in London, Ont.

A 2020 survey conducted by Leger for RE/MAX Canada found 32 per cent of Canadians would rather live in rural or suburban communities than a big city. This trend is stronger among young Canadians under 55.

“Everything, it’s always been directed towards urban centres. So, this is new,” said Haan. “I think the pandemic has really pushed younger generations especially, to look outside of urban areas a bit more than they would have normally.”

Part of the problem also comes from the widespread uptake in remote work. More white-collar workers are now able to live and work from anywhere in the country. While small towns usually would benefit economically from a population increase, remote work complicates things.

caption

Michael Haan“What we’re seeing now is the people moving to smaller towns, they already have jobs,” said Haan. “So, a lot of the acute labour shortages that smaller communities have been facing aren’t being solved by this latest wave of migration.”

As the county attracts more people, infrastructure has been struggling to keep up. Dowdall said local businesses like wineries, artisan shops and agriculture jobs are beginning to suffer: “We cannot get people to work here in hospitality. They just can’t afford it,” he said.

As the executive director of the Prince Edward County Affordable Housing Corporation, Dowdall routinely brings new ideas to county council meetings on this issue. One recent staff recommendation is to amend the county’s zoning by-laws to allow for inclusionary zoning. This means new construction projects would need a certain amount of affordable housing units in their application to get approval from council. Another recommendation is to allow the development of tiny home communities.

“I took all the councillors last week on a bus tour so they could see the inside of this 262 sq. ft. home. It’s beautiful,” he said. “They even have a built-in wine fridge for God’s sake. I wanted to dispel the myth that a tiny home is just a Canadian Tire utility shed.”

Options like tiny homes will help the supply side of the issue, but there is more to contend with than just the dwindling number of available homes.

The list of factors that led to Canada’s housing crisis is long and complex: historically low interest and mortgage rates set by the Bank of Canada, a low supply of new housing and rental stock, long wait times for site planning applications, a growing demand for more single-family dwellings with more space, all contributing to skyrocketing prices.

Housing is not a simple issue to study from a policy perspective, because it doesn’t fall neatly under one level of government. Historically, all levels of government have been responsible for different areas of Canada’s housing system at different times. The federal government has largely been responsible for creating national housing policies, insuring mortgages through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and helping new homeowners through tax-expenditures, grants, and government-backed loans. Provinces and territories took on a more active role in housing during the 1970s by creating provincial housing departments to help decide where to spend federal funding, offer tax-credits, and control rental prices. Municipalities are mostly responsible for deciding where federal and provincial funding goes — and how neighbourhoods are zoned for different types of housing. They also encourage developers to build higher-density more affordable units.

By 1993, the federal government had shifted the duty of affordable housing to the provincial, territorial, and, in some cases, municipal governments. This left municipalities to take over a large part of what had been a mostly federal issue and resulted in small towns across the country struggling for almost 20 years. That changed in November 2017 when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the National Housing Policy.

Tofino, B.C.

Nestled into the northern tip of the Esowista Peninsula, on the west coast of British Columbia’s Vancouver Island, Tofino has, for decades, been a prime destination for surfers, creatives and tourists. Once a small, isolated fishing village, it has grown into a hot spot that hosted an estimated 600,000 visitors in 2018.

To an outsider, the annual wave of adventure seekers who flood the town’s beaches, bars and bunkhouses should be a boon for local businesses. But for the 2,500 Tofitians who call this picturesque town their home, this year’s pandemic-fuelled flood of home buyers has left many locals treading water.

“I’ve been watching people who have invested their lives in this community for 20 years get pushed out because they can’t afford a home,” said Tofino real estate agent Tia Traviss. “I know plenty of elderly residents who just want to downsize but can’t.”

Traviss said Tofino’s housing market was growing long before COVID-19, but when prices skyrocketed in big cities, her town was swarmed with buyers. Data from Statistics Canada shows that while Tofino’s population grew from 1,967 in 2016 to 2,516 in 2021, the number of available homes has increased only to 1,205 from 1,078.

caption

Tia TravissThe affordability crisis plaguing urban centres has followed those looking to escape it. In Tofino, properties that sold for $1 million pre-COVID are now getting multiple bids, selling at almost double the asking price. Traviss said even rental properties have bidding wars, and some tenants are offering up to a year’s worth of rent up front.

Another factor is the number of short-term rentals operating in Tofino. Data from AirDNA, a market research firm based in Denver, Colo., suggests there are 335 current active listings in the area.

Traviss said the incentive for homeowners to keep renting out their investment properties on the long-term rental market simply isn’t enough. “When someone realizes what their vacation suite can make on Airbnb, it’s hard for them to resist that added income,” said Traviss.

The District of Tofino permits short-term rentals through municipal zoning bylaws, designating them as commercial use properties rather than residential. Operators also need a business licence from the district.

“It’s ruined our town completely,” said Traviss.

While some in rural communities can hope to make some easy money by listing their property on Airbnb, the sharing economy’s effects on housing markets are still not fully understood. To get a better understanding of how worried these communities should be, we should get some context first.

So, what about Airbnb?

The growth of the sharing economy in the last decade has allowed peer-to-peer services such as Airbnb to flourish. Airbnb states on its website: “On any given night, 2 million people stay in homes on Airbnb in 100,000 cities all over the world.”

CEO Brian Chesky started by renting out air mattresses in the basement of his San Francisco apartment. His company is now listed on both the Toronto and New York stock exchange and is valued between $18 billion and $31 billion.

At the outset, Airbnb was meant to be the cheap alternative to staying at a hotel. Don’t feel like booking the Hilton for your 12-hour layover in Toronto? There’s an empty basement apartment for $50 a night down the street. For many Millennial travellers on a budget, it’s an attractive alternative to hotels and hostels.

This shift away from popular hotel chains is part of a larger change in tourism. Experienced travellers naturally start looking for newer experiences. They want a good story to tell at their next barbecue.

There is a demand for modern travel to be authentic and exciting — Airbnb fills that demand.

With the introduction of Airbnb’s Insider Guidebooks in 2016, hosts could now share their neighbourhood’s best spots for late-night tapas or early morning brunch with their guests right on the app. This put the company in direct competition with review services offered by Google, Facebook, and Yelp.

Insider Guidebooks was launched side-by-side with Experiences: Airbnb’s newest add-on to its booking service. As the name suggests, it allows travellers to book activities hosted by locals, through Airbnb’s portal. Users can go truffle hunting in France, stroll with alpacas in Quebec, or try their hand at pasta-making with a real Italian grandmother.

Despite its success, Airbnb was hit hard when the pandemic came knocking. In a message posted to its website last spring, Chesky confirmed the layoffs of around a quarter of Airbnb’s 7,500 employees. Even after cutting its workforce, Airbnb still managed to generate $1.5 billion in Q4 revenue, 20 per cent higher than the previous year.

As with many disruptive innovations, Airbnb’s remarkable growth over the past decade has made it the target for accusations of gentrifying residential neighbourhoods, fuelling over-tourism, and more recently, draining local housing markets of available homes.

Airbnb and the housing crisis

Housing crises in both Canada and the United States have forced the consequences of Airbnb’s growth into sharp focus.

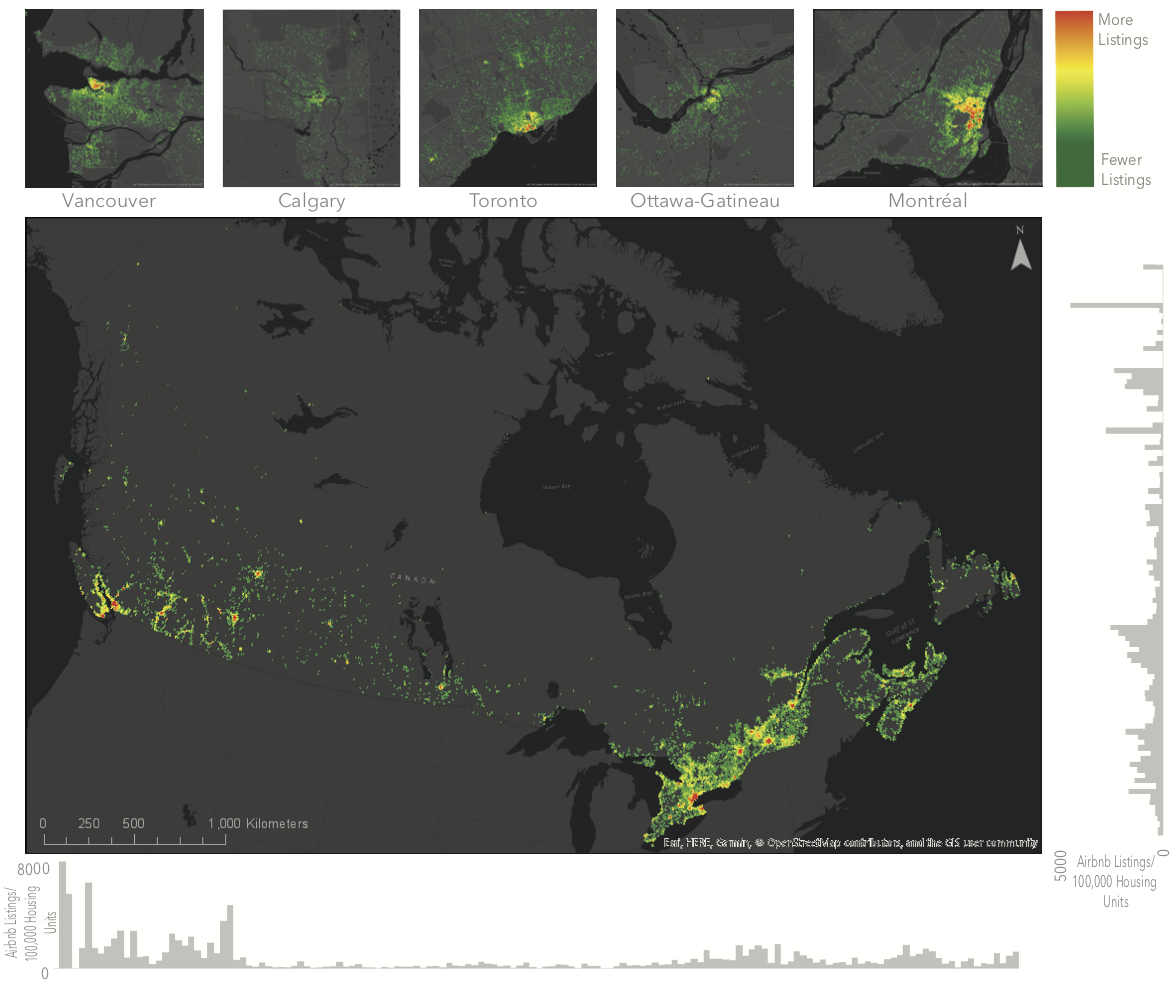

In a 2019 study: “Short-term rentals in Canada: Uneven growth, uneven impacts” researchers from the School of Urban Planning at McGill University conducted “the first comprehensive analysis of short-term rental activity in Canada.”

The report estimates short-term rentals have removed a total of 31,000 units of housing from long-term markets in Canadian cities. That figure is based on the number of frequently rented entire-home listings available for at least half the year and rented for at least 90 days. Rural communities, those with less than 10,000 residents, saw an increase of 60 per cent in frequently rented entire-home listings — almost double that of major cities.

caption

This histogram shows the density of short-term rental properties across Canada.The data gathered by the South Short Housing Action Coalition supports these findings. In Lunenburg, N.S., for example, 89 per cent of the 277 listings are for entire homes.

In Prince Edward County, city staff completed a report last January placing the number of entire-home listings at 536 of the total 797 listings.

The McGill report notes these types of listings represent a conservative estimate of housing loss, but their high growth rates are still a cause for concern. As of December 2021, there are more than four million hosts renting out the six million active listings worldwide on Airbnb.

A greater number of properties than hosts means some hosts operate more than one listing, which can be for a single room, multiple rooms, or an entire home. Having multiple listings at one location is within Airbnb’s terms of service and these multi-unit hosts can make a lot of money.

Multi-unit entire-home hosts account for 30 per cent of revenue generated but only seven per cent of all hosts in Canada according to a 2017 report prepared by CB Richard Ellis Ltd. for the Hotel Association of Canada.

In a 2020 research paper, Andrea Shillolo, a master’s student in McGill University’s Urban Planning department, compared Airbnb’s effects on rental housing markets in New York City and Toronto. Both cities are struggling with housing affordability crises and low vacancy rates. Both cities are also major travel destinations for tourists, meaning demand for accommodations is also high.

Shillolo identified “ghost hotels” as a major source of housing loss in both city’s markets.

“A ghost hotel may appear like a home-sharing arrangement, but it is effectively a hotel, and furthermore it may be hiding in plain sight […] its component listings appear to be separate, single-room rentals.”

This form of listing could mean early estimates of housing loss were too conservative. Previous research has focused mostly on entire-home listings as a measure of loss.

Lastly, ghost hotels present major challenges for the hotel industry: while they operate like a small-scale hotel, they are exempt from the same zoning, safety, and tax regulations.

“Not only is Airbnb facilitating the conversion of properties into short-term rentals, it is enabling users to do so in covert ways which have slipped past regulators’ attention,” Shillolo concluded.

The grey area

A major challenge in regulating short-term rentals is how quickly Airbnb has spread. Just five years ago, Québec finally became the first region in Canada to introduce legislation requiring short-term rental operators to register their properties with the province. Other provinces and municipalities across Canada have implemented regulations in one form or another, and still more are starting the conversation.

The city of Brampton, Ont., passed an updated bylaw in September, restricting short-term rentals to the operator’s primary residence, effectively barring the use of investment properties for short-term rentals. Operators will also require a special municipal licence.

City staff in Charlottetown, P.E.I., presented a set of rules to the municipal planning board in October. The proposal would disallow short-term rentals in apartment buildings and would limit the number of listings to one. Operators would also require city and provincial licences

Winnipeg, Man., is exploring regulatory measures related to proper taxation, licensing and fire safety standards. In Saskatoon, short-term rental operators require a commercial business licence, a host declaration, and discretionary use approval from the city in certain zoning districts.

These conversations are no doubt promising, but regulations and bylaws are only part of a solution. Ren Thomas, an associate professor in urban planning at Dalhousie University, said there isn’t a strong incentive for some rural areas to crack down on short-term rentals.

“In a lot of cases, these smaller communities are tourism hot spots, and they rely heavily on that tourism income. Short-term rentals keep people coming to their communities, so it’s understandable why they don’t want to do anything to discourage that,” said Thomas.

Smaller communities also typically have fewer resources to make policies that ensure are following local bylaws.

South Shore, N.S.

On the southern coast of Nova Scotia, members of the South Shore Housing Action Coalition are tackling the same issues as in Prince Edward County and Tofino.

Helen Lanthier has been a member for more than a decade. She said one of the most pressing issues is getting people to acknowledge the housing crisis in rural communities. “Until recently, it was just assumed that there was no housing crisis in rural Nova Scotia,” said Lanthier. “But that’s simply not the case.”

caption

Helen LanthierData collection is a vital part of the solution, one that Lanthier said is severely lacking in rural communities. Access to better housing data was one of many recommendations tabled in the Nova Scotia Affordable Housing Commission’s 2021 report.

“If we don’t have meaningful data to show the provincial or federal governments, it’s much harder to show how desperate the situation is,” said Lanthier.

The report’s authors note municipalities often don’t have sufficient expertise or autonomy when it comes to their role in providing affordable housing: “Communities must be able to study their own housing needs and demand, but they lack sufficient capacity or resources to do so.”

Francis Kangata, deputy mayor of Mahone Bay, N.S., has seen these challenges first-hand.

“I think, until recently, it’s been difficult for municipalities to see themselves as a key player in addressing their communities housing concerns,” said Kangata, who helps administer the town, located an hour’s drive southwest of Halifax.

Lanthier and Kangata agree the pandemic has put more pressure on both residential and rental markets, bringing the need for affordable housing into stark focus.

“I think historically, we’ve been concerned with housing those experiencing extreme poverty,” said Lanthier. “But this is the first in 10 years doing this work that I’ve run into this issue of couples and families with a stable income not being able to find an affordable place to live.”

Communities on the South Shore are also grappling with the explosion of the short-term rental market.

In 2019, the South Shore Housing Action Coalition prepared reports for each municipality in the region.

These reports recorded a total of 790 active listings for apartments and entire homes, with the latter representing most listings.

The crux of the issue is that short-term rentals are more profitable as a homeowner’s second property than long-term rentals. Short-term rentals are made to serve tourists rather than people who live and work in these towns.

As of April 1, 2020, short-term rental operators in Nova Scotia must register their properties with the province and pay an annual fee, between $50 and $150 depending on the number of bedrooms.

This was one of the first solutions brought forward by local advocates in order to “level the playing field” between short-term rental owners and commercial operators in the tourism industry.

“They are here to stay, so the question is: ‘How do we ensure that the impacts remain positive?’ The huge piece is still regulation, and regulation in a way that makes sense,” said Kangata.

While heavy regulation may seem like a no-brainer, many small towns — especially those near the coast — rely on their tourism industry to sustain the economy. Tourism in Nova Scotia still earned an estimated $1 billion in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, down from $2.64 billion in 2019.

Lanthier said she sees both sides of the argument. While short-term rentals chip away at available rental and residential housing stock, they also provide a place to stay for incoming tourists looking to spend money.

“We know our communities need short-term rentals to continue growing, but we also need reliable data and the policy resources to regulate them,” said Lanthier. “Change is slow, but it’s happening.”

As provincial and municipal governments grapple with how best to regulate short-term rentals, Ren Thomas, an associate professor of urban planning at Dalhousie University, said cooperation across all levels of government will be essential to striking the necessary balance.

“One part of this that people often miss is looking across the country, or even across the world, at other cities and countries who are trying different approaches to this issue,” said Thomas. “We absolutely cannot afford to have tunnel vision on this issue.”

What’s next?

So, where do we go from here?

Haan said it’s hard to tell whether the migration away from urban centres would continue in a post-COVID-19 Canada, or if it’s just a symptom of the pandemic.

“That’s the million-dollar question, right? What we’re starting to see is our major centres are growing a little slower compared to the last 20 years and the population is distributing itself more evenly across the country,” said Haan. “This isn’t the same rural Canada from the 1980s, so we’ll have to follow it closely — we’re in uncharted territory.”

While the federal government signalled its re-entry into the issue of affordable housing in November 2017, it remains to be seen whether it delivers on lofty pre-pandemic promises it made as the country enters another year of living with COVID. The pandemic has proven to be a catalyst for debates surrounding a complex issue like affordable housing.

“It can’t all be about dollars and cents,” said Dowdall. “We need to start thinking about people again.”

“I think we’ve been shocked back to talking about very basic things as a society,” said Kangata. “Our politicians have been forced to circumvent all the bureaucracy and noise that surrounds these basic issues to face these things head so we might be able to start doing things differently and that gives me hope.”

Editor's Note

The story was produced as the capstone project for the Master of Journalism degree. Top image by Benjamin Elliott

About the author

Benjamin Elliott

Ben Elliott is a reporter for the Signal at King's College in Halifax. He got his HBA in Communication Studies from the University of Waterloo...

J

Joanne Quinn

M

Mark Hauser