SMU astronomers glimpse into cosmic past with new discovery

Discovery is beginning to uncover some of the oldest secrets of the universe

caption

This image from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope depicts IC 1623, an entwined pair of interacting galaxies which lies around 270 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Cetus.Astronomy researchers at Saint Mary’s University are using the world’s most powerful telescope to observe the deep reaches of outer space.

Dr. Marcin Sawicki and doctoral candidate Yoshi Asada are part of a Canadian research program that studies distant galaxies. A paper authored by the pair earlier this year announced the discovery of a galaxy roughly 13 billion light-years away, making it one of the most remote objects ever studied.

The team spotted the object using the James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful space telescope in existence. Since its launch in 2021, it has delivered the most detailed images of outer space on record.

In astronomy, most objects are so far away from Earth their light takes a long time to reach us. Scientists use the term light-year, a unit of distance, to describe the light’s travel time through space.

Asada and Sawicki’s galaxy is roughly 13 billion light-years away. When they spotted it using the telescope, they were actually observing it as it was 13 billion years ago.

Sawicki, a professor of astronomy and physics at SMU, was thrilled by the opportunity to work on the Webb telescope. For him, the technology is interesting because it allows us to gaze into the past.

“Webb is a time machine,” says Sawicki. “We can’t travel back in time the way Doctor Who does, but we can use physics to do it.”

Compared to our own solar system, said Sawicki, their discovery is relatively old. “Our sun is only 4.5 billion years old – it did not exist when the light from those galaxies was emitted.”

caption

Dr. Marcin Sawicki (left) and Yoshi Asada (right) observing their discovery in Sawicki’s office at Saint Mary’s University on Oct. 14, 2023Sawicki was one of the founding members of the Canadian science team on the Webb telescope. The team helped to develop two instruments aboard it. His contribution is called NIRISS, an instrument meant to help astronomers get clearer images of deep space. When the telescope launched, Sawicki and his research team were awarded guaranteed observing time as an acknowledgement of his contribution.

It was during this window that Asada and Sawicki made their discovery. During a survey of deep space, they spotted two small galaxies in the process of merging. Their scientific names are ELG1 and ELG2, but the team casually refers to them as a single entity — a “baby galaxy.” It is relatively small, roughly one ten-thousandth the size of our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

Sawicki, a specialist in galaxy evolution, said studying this object allows us to understand how galaxies formed in the early universe. One of the central theories of his field says smaller galaxies should merge to form larger ones, like LEGO blocks. Until now, this theory had never been tested on an object so young.

“We wanted to know if it is true at these distant epochs,” said Sawicki.

Asada authored a second paper that surveyed a wider area of space. He wanted to find more examples of “baby galaxies” undergoing mergers. Of the roughly 120 galaxies they observed, about half were interacting with each other. These findings are beginning to prove the building-block theory, said Asada.

“The baby galaxies we found should be archetypical galaxies in the early universe.”

Sawicki and Asada are both excited about the implication of their discovery for the future of astronomical research.

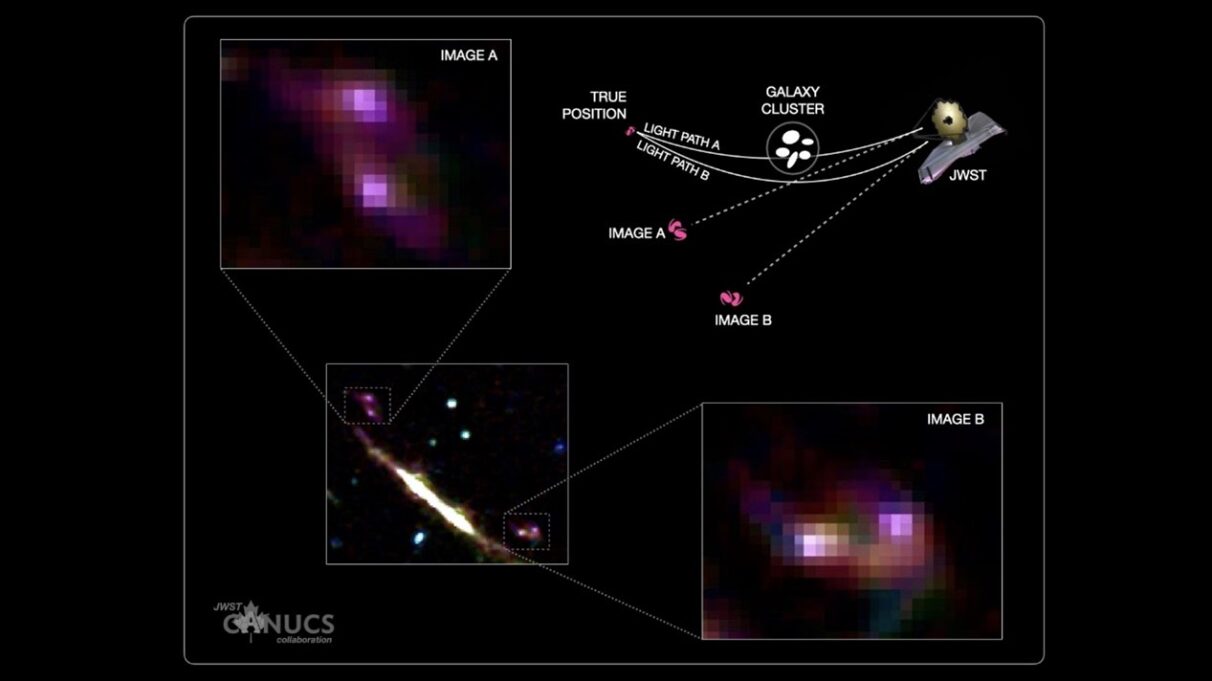

caption

An image of Sawicki and Asada’s “baby galaxy.” The two smaller bodies, pictured in images A and B, are merging into a single, larger galaxy.“The observations with (the Webb telescope) are striking. The results have revolutionized our understandings in various fields,” said Asada, who is already working on another paper based on their data. “They have opened a new era of astronomy.”

For Sawicki, the study of distant galaxies is interesting because it may hold clues to humanity’s cosmic past.

“We are learning the story of our origins,” he said. “The galaxy that we observed is a representation of what our past may have been like here in the Milky Way.”

About the author

K.C. Jordan

K.C. Jordan (he/him) is a journalist working in Halifax, N.S. He has reported on business, sports and science for The Signal, the Dalhousie Gazette...