Stepping into the future

caption

A person is biking through the street in Halifax surrounded by cars.Why some cities become more pedestrian-friendly while others idle in the past

When Colleen Sparks moved to Victoria 20 years ago, she was terrified to bike in the city. From cars honking to trucks blowing black smoke in her face, cycling meant coming face-to-face with each driver’s 2,000 kg personality.

Victoria has come a long way in 20 years. Now Sparks can ride to work and feel safe. Designated bike lanes run parallel to some of the major roads; by this time next year, her commute will be entirely in bike lanes. “I feel really lucky,” says Sparks. “I’m blessed to be able to cycle.”

She isn’t alone. Studies show that people are happier and healthier when they can walk or cycle every day. An article by Laurie Berrie of the University of Edinburgh School of GeoSciences, and colleagues, published in the International Journal of Epidemiology in February 2024, said that people who cycle to work are 15 per cent less likely to use prescription pills for depression and anxiety.

So why doesn’t the infrastructure of Canadian cities always include walking paths and bike lanes?

Pushing limits

Urban density makes cycling and walking easy. Urban sprawl, though, defines North American infrastructure. After the Second World War, private automobiles became enshrined in people’s daily routines. This allowed for a massive exodus from urban centres. Cities across the continent were drained of upper-middle-class families. Where did people go? The suburbs.

Urbanization continues today. From 2022 to 2023 alone, Statistics Canada says, spending by businesses and government on housing infrastructure rose 14 per cent ($4.7 billion to $5.3 billion), Since 2016 it has grown 67 per cent ($3.2 billion).

Activists in Canmore, Alta., in February 2024 protested new developments that would expand the city into the Grizz Corridor. That’s the last wildlife migration link between Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country.

What connects communities as sprawl expands? Once upon a time, it was interurban streetcar networks. Eventually, streets became crowded and gridlock kept streetcars from operating efficiently. Eventually, cities including Toronto and Montréal replaced their interurban streetcars with buses.

Still, in Canada the car is king. Yearly spending by businesses and government on buses and trains is down 25 per cent from 2016 ($2.7 billion, down from $3.5 billion) while investments in highways are up 53 per cent ($23.7 billion, up from $15.5 billion).

Most Canadian cities aren’t very dense and their infrastructures have nearly a century’s worth of car-centric bias. It’s no surprise, then, that for pedestrians and cyclists roads have become dangerous. CAA says that collisions with cars, on average, kills one cyclist in Canada every week. In the United States, a cyclist dies every nine-and-a-half hours. That’s 1,360 people every year—a 47 per cent increase from a decade ago. Statistics Canada reports things are even worse for pedestrians. Between 2018 and 2020, 300 Canadians a year died after being hit by vehicles.

Perrotta used to live in Toronto and enjoyed walking or taking streetcars. After moving to the suburbs, she continued working in the city for years. The stress of making the train on time and the hours commuting left her drained. She didn’t have time for the recreational walking that people in the suburbs supposedly enjoy.

“I’ve seen (how commuting affects) my mental stress and my physical activity, (and) you can see it in the studies,” says Perrotta. “If I had known that 22 years ago, I wouldn’t have moved here.”

Cities like Victoria are becoming more walkable, but not many people can afford to live in such places. The cost of condos in Victoria, in summer 2024, rose three per cent every month. Perrotta believes this is proof that Canadians want dense, accessible neighbourhoods. She says that with more affordable housing initiatives, and by developing bike lanes in cities, the cost of living can be managed.

“Neighbourhoods are getting more expensive,” says Perrotta, “but it’s because we all want to be there.”

Cars rule

The need for walkable infrastructure is not the death of the car. In Calgary, John Morrall has mostly retired from his work as a civil engineer, although he still accepts calls for his professional opinion. Morrall remembers his most beautiful project, the Sea to Sky highway in B.C.. Completed in 2009, Morrall made sure it was safe for drivers and pedestrians. He recommended an 80 km/h limit and a bike lane from the Horseshoe Bay ferry terminal along 98 kilometres of highway to Function Junction. He says that, these days, all kinds of transportation “have to be considered.”

Morrall only makes recommendations; it’s up to politicians to adopt them. Ontario Premier Doug Ford has introduced a bill to ban construction of bike lanes that take space from vehicle traffic. He also plans to remove problematic bike lanes to “bring sanity back to bike lane decisions.” Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow, meanwhile, hopes to continue her plan to improve Toronto’s cycling network.

Every cyclist is one car off the road. That is good for traffic. So why aren’t cycling initiatives more welcome?

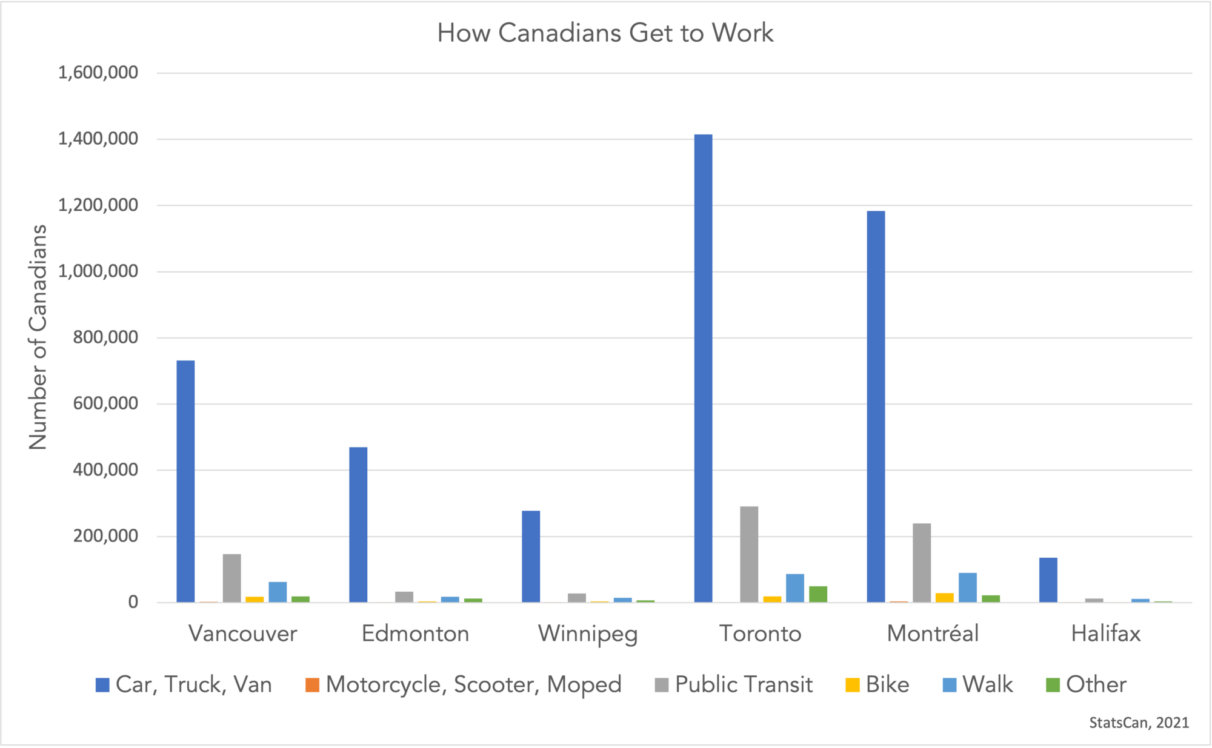

Back in Victoria, Corey Burger is a retired board member of Capital Bike and a senior data analyst for Malatest, a research firm. He studies how Canadians get around. Unsurprisingly, most of us drive to work. Statistics Canada says the figure was 84 per cent in 2021, up from 78 per cent in 2016.

Burger has an idea that might help. “Build a lot more bike lanes,” he said. “It sounds trite, but it’s absolutely the truth.”

Burger says policy makers should remember who they’re helping. He can watch the traffic heading in and out of his city every day. He sees each individual person sitting in their car. “Those are people trying to go home from work,” he says. Their commute is draining and their climate impact hurts the ecosystem. But for most of those drivers, he says, “that’s the choice… that’s available.”

Alternatives

People need more options. Finding inspiration often means looking elsewhere. Now the international crown jewel of cycling, Amsterdam used to battle severe gridlock. Since the 1970s, though, the city has worked to stop sprawl and calm traffic. This meant reducing the number of cars, changing street designs, and listening to citizens who grieved for loved ones lost to car accidents.

Marjolein de Lange is a mobility expert for Fietsersbond Amsterdam, the city’s cycling union. Like Capital Bike, her organization works with government to improve walkability and cycling culture. The cycling network, she says, is “a living thing.”

De Lange has a message for countries like Canada: be precious with space. “Don’t give all your space away to cars.” Big cities might be difficult to change overnight, she says, so start with small ones.

In Victoria, Colleen Sparks hopes her city becomes more like Amsterdam. “You notice so much more when you’re cycling. You appreciate your neighbourhood so much more. It really is a different way of experiencing the world around you,” Sparks said. “My husband and I cycle-travel. We don’t go very far, but we sure see a lot.”

About the author

Eamon Irving

Eamon Irving will graduate this spring with a Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) degree from the University of King’s College.