Health

Street clinic

MOSH brings health care to people living on the streets, while Halifax faces HIV outbreak.

It’s a Thursday morning in March, and the red Toyota Sienna is ready to start on its route from the North End Community Health Centre on Gottingen Street through the streets of Halifax. To most, the van goes unnoticed. Besides the slightly raised ceiling, the only distinguishing feature on the van is a vanity plate that reads “MOSH.” But to the vulnerable community of people living on the streets of Halifax, this van is recognized as a lifeline.

The van is equipped with an examination chair where the vehicle’s backseats would normally be. The flooring has been replaced with industrial ceramic and a small cabinet has been installed, full of basic medical and harm-reduction supplies. A nurse waits inside.

Six days of the week, the Mobile Outreach Street Health team (MOSH) brings its clinic-on-wheels to shelters and soup kitchens around the city to provide access to medical help for homeless or insecurely housed people. From the van, the staff offer private appointments, give injections, perform on-the-spot care and connect people with physicians. Stepping into the van is like stepping into a doctor’s office.

Rick Swaine is an outreach nurse for MOSH, and Eric Johnson is a Spring Garden Road street navigator, someone who works with people living on the streets, helping them with housing, employment and other needs. Together, they patrol the streets of Halifax searching for people in need of medical or social care. This Thursday, Swaine has a list of names and descriptions of people who need assistance or a check in. The list is compiled by the North End agencies MOSH partners with in order to reach everyone in the community.

Swaine has his regular pack of clean medical supplies with him: stethoscope, bandages, ibuprofen.

caption

Rick Swaine, an outreach nurse, gets his pack ready with medical supplies for a day on the streets.He is prepared to treat blisters and sprained ankles, but these days they are dealing with something much more serious: an outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS.

The van pulls away.

In the basement of the North End Community Health Centre is the MOSH walk-in clinic. A small sign hangs on the glass door saying the clinic is closed and giving a phone number for a nurse practitioner to call if you need help.

A young man with a torn grey hoodie, tattooed knuckles and a guitar slung over one shoulder walks in and sighs with disappointment at the sign. He was here yesterday and was faced with the same disappointment. With no cellphone, he waits patiently.

Having only been open for a year and with little funding, MOSH’s walk-in clinic has a doctor one-and-a-half days of the week, with a nurse practitioner and a few casual nurses helping out.

Calling the number on the sign leads to Jac Atkinson, a nurse practitioner who will take the van to wherever someone needs help. From the van, Atkinson can perform all primary medical procedures, except intimate checks such as pap smears. She is able to conduct anything from blood testing and screenings to regular check ups.

“There is no typical day with MOSH. From seeing 20 to 60 clients a day, the job is immediacy-based and requires flexibility,” said Atkinson.

caption

Jac Atkinson, nurse practitioner at MOSH, stays after hours to finish meetings with clients at the clinic on Gottingen Street.Atkinson said she could start her day at the Metro Turning Point Shelter on Barrington Street, spending a few hours helping patients with basic health care, then suddenly receive a call from a client who is contemplating suicide. She will go to their home, or find the park they’re sleeping in, and offer help. After, she returns to visiting shelters or walking up and down Spring Garden in search of someone who needs her help. Establishing relationships and building trust is a means to improve health.

Chaotic lifestyles

Access to the existing health care system is difficult and even impossible for many people living on the margins of society due to chaotic lifestyles and negative stigma from medical professionals, said Atkinson.

“The population that we work with — intravenous drug users and severely mentally ill people — there is this major stigma that it’s their fault and it’s their choice,” said Atkinson. “Once you get painted that picture or that label, it’s really hard to get out from under the rocks, and people don’t want to work as hard for you or provide the same level of care because they just assume that you’re either not worthy of it, or not going to appreciate it or not going to make full use.”

Past the frosted glass doors of the MOSH walk-in clinic, Heather Nicholson works in her office as the health case manager.

caption

The MOSH clinic looks like a regular clinic, with a hall of examination rooms.She said people in this community are transient and difficult to contact. Due to many of them not having stable homes, or phones, calling them to remind them of appointments is not an option.

“By the time the appointment comes around, you’ve lost them,” Nicholson said.

By opening their own clinic they are bridging that gap and making it possible to receive immediate care. Also, if a person has lost their health care, they generally cannot be seen at a walk-in clinic in the city. MOSH and the North End Community Health Centre can work around that.

“I think it’s a huge step forward for MOSH and it is serving a great need in the community,” said Nicholson.

MOSH has become vigilant about encouraging testing at their clinic for those who are at risk of being infected by HIV, specifically those who are injecting drugs. It is a layer of care that has always been on the back burner, but has now become a priority due to an HIV outbreak in the community.

Testing everywhere

Atkinson said the MOSH team has a close relationship with almost all of the people injecting drugs in Halifax and Dartmouth and talking to users about their experiences and fears is key to making sure they are aware of all the harm-reduction tools available to them to prevent further spread.

“We are testing everywhere, but we just don’t have the manpower to do it all,” she said.

According to the Nova Scotia Health Authority, Halifax is facing an HIV outbreak after having seen an abnormal spike in HIV cases during the summer of 2018. By the end of 2018, 29 new cases of HIV were confirmed in Nova Scotia. This is 16 new cases above the provincial average in the past 10 years. In 2017, there were only 15 new cases.

For the past 10 years the highest risk for HIV in Nova Scotia has come from men having sex with men. Second was people injecting drugs. From 2012 to 2015, on average seven per cent of new cases were attributed to injecting drugs. By 2017, 20 per cent of new HIV cases were attributed to injecting drugs.

As of December, 2018, the Public Health Agency of Canada had reported 48.3 per cent of new cases in Halifax were attributed to injecting drugs — over double the previous two years.

Made with Visme Infographic Maker

This is making access to clean needles, education programs, and testing essential.

At the QEII Health Sciences Centre, Dr, Lisa Barrett, an infectious disease physician, works with those who have been recently diagnosed.

As many of them are still injecting drugs, Barrett said it’s important that they know HIV can be transmitted through blood on dirty needles. Many think of it only as a sexually transmitted disease.

“The fact that we haven’t recognized the risk of blood-borne pathogens like Hep C and HIV as being significant contributors to poor health — because we haven’t really focused on that in people who inject drugs — has really allowed it to be an issue,” she said.

Across Canada, new HIV cases increased in 2015 and 2016 after several years of relative stability, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. There were 11.6 per cent more new cases in 2016 than 2015, the agency said.

Nova Scotia’s rate of new infections per 100,000 has been far below that of Canada overall. Even with the spike in 2018, Nova Scotia’s rate would still be far lower than that in provinces outside Atlantic Canada, when compared to the most recently available national figures from the Public Health Agency. The highest rates are in Western Canada.

Compound interest

Atkinson said it doesn’t take much to cause an outbreak of HIV and it is difficult to pinpoint where it starts. Once one person in the community is infected, they pass it on.

“It just kind of multiplies. It’s like compound interest,” she said.

When asked if stigma towards people who inject drugs has contributed to the outbreak, Atkinson said, “Absolutely, no question. These folks are tired, and their immunity is at ground zero.”

Jeff Doffney is one of those people.

Doffney’s addiction to illicit drugs began at the age of 11. He jumped from home to home as a child, facing sexual abuse and a sense of hopelessness. Over his 22-year struggle with addiction, Doffney was in and out of prison several times, causing him to lose jobs, and he lived in insecure housing. When the time came to find help, he rarely found an empathetic hand.

Two years ago, after a fight with his girlfriend and the unshakable feeling he was about to lose her, he felt desperate and went to a former friend’s home, up the street from his, to use drugs.

He went to the washroom, leaving his supplies in the other room. When he returned, he used one of the needles, not knowing it had been contaminated by HIV.

“I must have shot up with some of his blood,” said Doffney, who was paid an honorarium by Mainline to do this interview.

That night changed his life forever.

With the help of Mainline, Halifax’s needle exchange, Doffney was referred to Direction 180, the methadone clinic on Gottingen Street, where he was tested and diagnosed positive for HIV.

“I feel like my life is over all the time,” said Doffney. “It holds me back in everything I try to accomplish in my life.”

Mainline helped Doffney get medical help, secure housing, figure out his taxes and the health-care system, and get treatments.

Doffney is now on an $80,000 treatment plan for Hepatitis C — covered by health care — which involves taking one pill a day for 12 weeks. His HIV diagnosis is treated with Triumeq, a large purple pill, which he will take daily for the rest of his life.

“It’s a tough pill to swallow,” he said, figuratively and literally.

Doffney’s health is stable and the HIV virus is undetectable in his blood, meaning he is no longer a risk to others. He recently moved into his own apartment and started working with a waste-disposal company. He remains vigilant to stay on top of his health and not be a part of HIV’s spread.

“It’s like cancer is the way I look at it. I need to live with this for the rest of my life.”

Expensive drugs

While Doffney’s stable health and medication prevents him from passing HIV to others, the ideal solution is to be protected from being infected in the first place.

One solution is Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), a preventative pill taken once a day to reduce the risk of contracting HIV. PrEP has been approved in Canada since 2016 and if taken regularly, will lower the risk of infection by 90 per cent when sexually transmitted, and more than 70 per cent when transmitted through injecting drugs.

“It’s the best tool in our tool box for preventing HIV,” said Barrett.

Since July 2018, it has been available to Nova Scotians via Pharmacare coverage. To cover it, prescription patients must be able to navigate the system, meaning they have filed taxes, filled out a special authorization form, and then remained stable enough to wait to get the drug. Otherwise, PrEP costs $260 a month.

This has made it difficult for people who inject drugs to gain access. Barrett said this is just one of the forms of stigma this community faces.

“We’ve set up a situation where we have said, ‘Yes, we will pay for your tool for prevention but we are not going to make it anywhere near easy to get to it,’” said Barrett.

At a panel discussion hosted by PrEP Nova Scotia on March 29, 2019, a panel of experts said it should be free for anyone.

British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan have taken this approach. In fact, British Columbia has seen reductions in HIV diagnoses since making it free to the public and is expecting an 83 per cent reduction in HIV diagnoses by 2026, said the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV-AIDS.

In the first year of PrEP being publicly funded by the B.C. government, more than 2,300 people in the Vancouver Coastal Health region started taking it.

“The treatment as prevention strategy has made great strides in improving the health of people living with HIV and in reducing HIV transmission in our region, where new HIV diagnoses declined from 174 in 2011 to 100 in 2017,” said Dr. Réka Gustafson, the agency’s medical health officer, in a statement provided by Coastal Health’s communications officer.

“We are now in a position to provide a highly effective preventive intervention to reduce transmission in our community even further.”

Understanding drug users’ lives

New Brunswick faces a similar problem with stigma from health-care professionals who don’t understand the chaotic lives people injecting drugs often live.

Brady Hooley, the education programs manager at AIDS New Brunswick, is working to sensitize healthcare professionals to issues around drugs, accessing testing and treating blood-borne illnesses by building an educational workshop for healthcare providers.

“It is important to understand that going about routine health care is not as easy for this group of people,” said Hooley.

The project will involve focus groups and consultations with people who are using drugs in order to hear solutions from both sides and ask what action needs to be taken. It is still in the building phase and is now seeking accreditation, which would mean physicians who take this educational program will be able to add it to their degrees.

“If this is successful, I wouldn’t be surprised if other provinces used the same program or adapted it,” said Hooley.

AIDS New Brunswick is hoping to have this program expanded to multiple health-service providers by 2022.

More testing

Right now, the most accessible defence against spreading HIV is regular testing. Barrett is heading a research program to roll out point-of-care testing in Nova Scotia.

“The test only involves a prick of the finger, similar to the test a diabetic performs, and provides results within three to five minutes,” said Barrett.

Health Canada has approved this test, which means it can diagnose HIV the same way a full, blood-draw test in a clinical setting would.

This is extremely beneficial for people who inject drugs because often times they do not have great veins, said Barrett.

“It’s really hard to get blood from these folks, and it’s a big stressor for them, which prevents a lot of health care and blood work from getting done.”

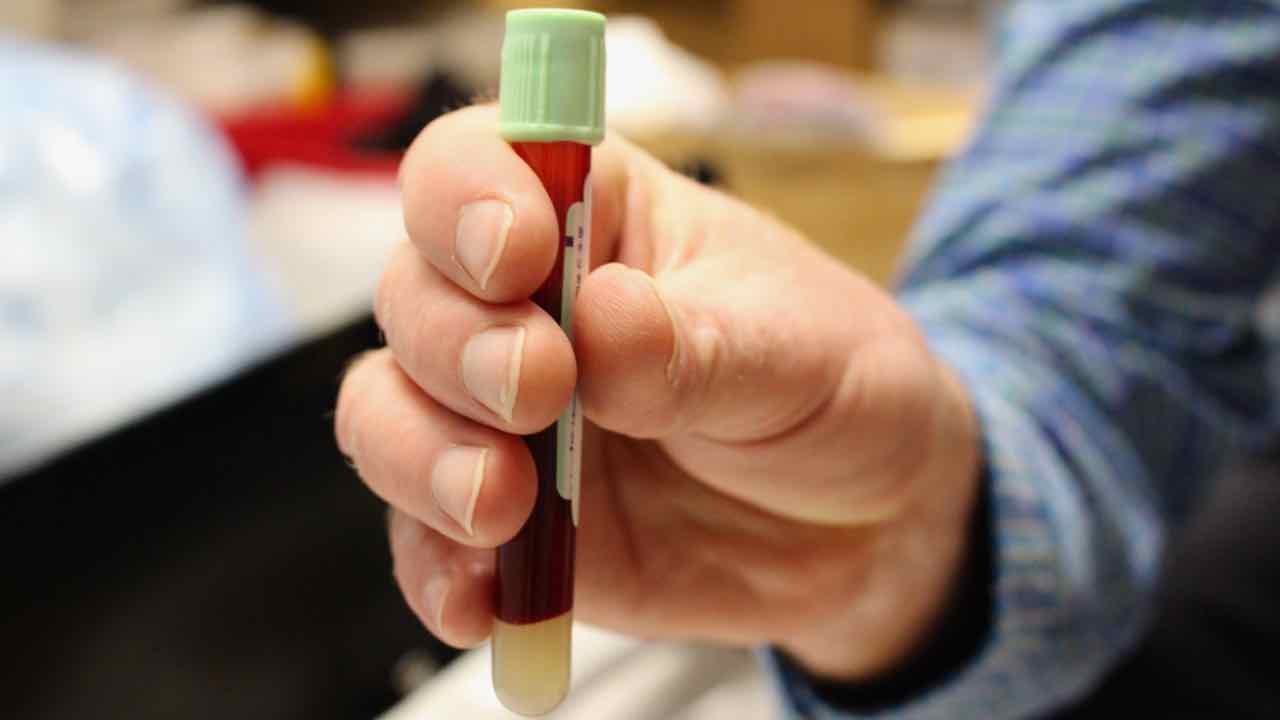

caption

After a full blood-draw test, samples must be safely packed before being sent away for results.The standard testing available now in hospitals is effective and only costs $3 a test compared to the $15 each point-of-care test costs. However, it is only effective if you have good veins, stable housing, and no problem getting to a hospital, which is a position not many people injecting drugs and at high risk of infection are in.

“The question isn’t whether it works, it’s whether or not bringing the test to people will actually increase the number of people they diagnose and treat because now they know their status,” said Barrett.

They also want to ensure there is an immediate link to care when someone is diagnosed with HIV.

“That is a health-system issue that needs to be developed and we are working on that,” said Barrett, adding that it will be a long time before the test is completely rolled out.

Safe injection

At the Mainline Needle Exchange on Gottingen Street, program director Diane Bailey gives people the same care and support her mother gave her for 25 years as she struggled with drug addiction.

In 1990, Bailey came to Mainline looking to work a few hours while going through a methadone program. She started with five hours a week, quickly doubling to 10 as she showed her dedication to the program and remained sober. When the position as program director opened up, Bailey was determined to get the spot.

“I never wanted anything more in my life, and I told [Mainline] they will never find anyone better for this job,” Bailey said.

Bailey has been the program director for 25 years and has helped Mainline partner with the community and run programs to help people injecting drugs in Halifax. She believes the best solution to lowering HIV’s spread is building a safe-injection site.

“I’ll hang my hat when we have community detox, safe places so people can use for months. If that’s what people need, then they can have it.”

caption

Yellow boxes like this one can be found in restrooms and clinics around the city in order to safely discard needles.Vancouver opened North America’s first official supervised injection site, Insite, in 2003, in response to a declared public health emergency due to high rates of HIV and overdose deaths among people injecting drugs.

“Insite has been a demonstrable success, preventing overdose deaths and reducing rates of HIV infection, while helping some of the most marginalized members of our community get addiction treatment and other important health services,” said Patricia Daly, the city’s chief medical officer, in an op-ed for The New York Times.

Bailey said Mainline Needle Exchange and Direction 180, a methadone clinic on Gottingen Street, have been talking with the city about opening a similar facility in Halifax.

Serendipity happens

After a day of patrolling the streets on Halifax, Swaine meets a client at the Halifax Central Library before getting into the MOSH van. He said he feels like a success every time he checks someone off his list. He saw most of the people he wanted to today, and found a few more he didn’t expect to see.

He gets in the driver’s seat to head out to Adsum House Women’s Shelter to help a client who needs medication, but then spots a woman walking down the street. He has been looking to bring her to the clinic for some tests and was starting to think he’d never see her again.

He jumps out of the van and calls her name; she responds with a welcoming smile.

“There are folks you’re watching out for, and there are folks you will ignore other phone calls for if you get the chance to have some time with them,” said Swaine. “Serendipity happens and you run into a couple people that way.”

Plans change. Instead of heading to Adsum House, Swaine asks the woman if she’ll come to the North End clinic with him to get those tests done. He can check another name off his list.

M

Marnie Fleming