Students give their mental health care a failing grade

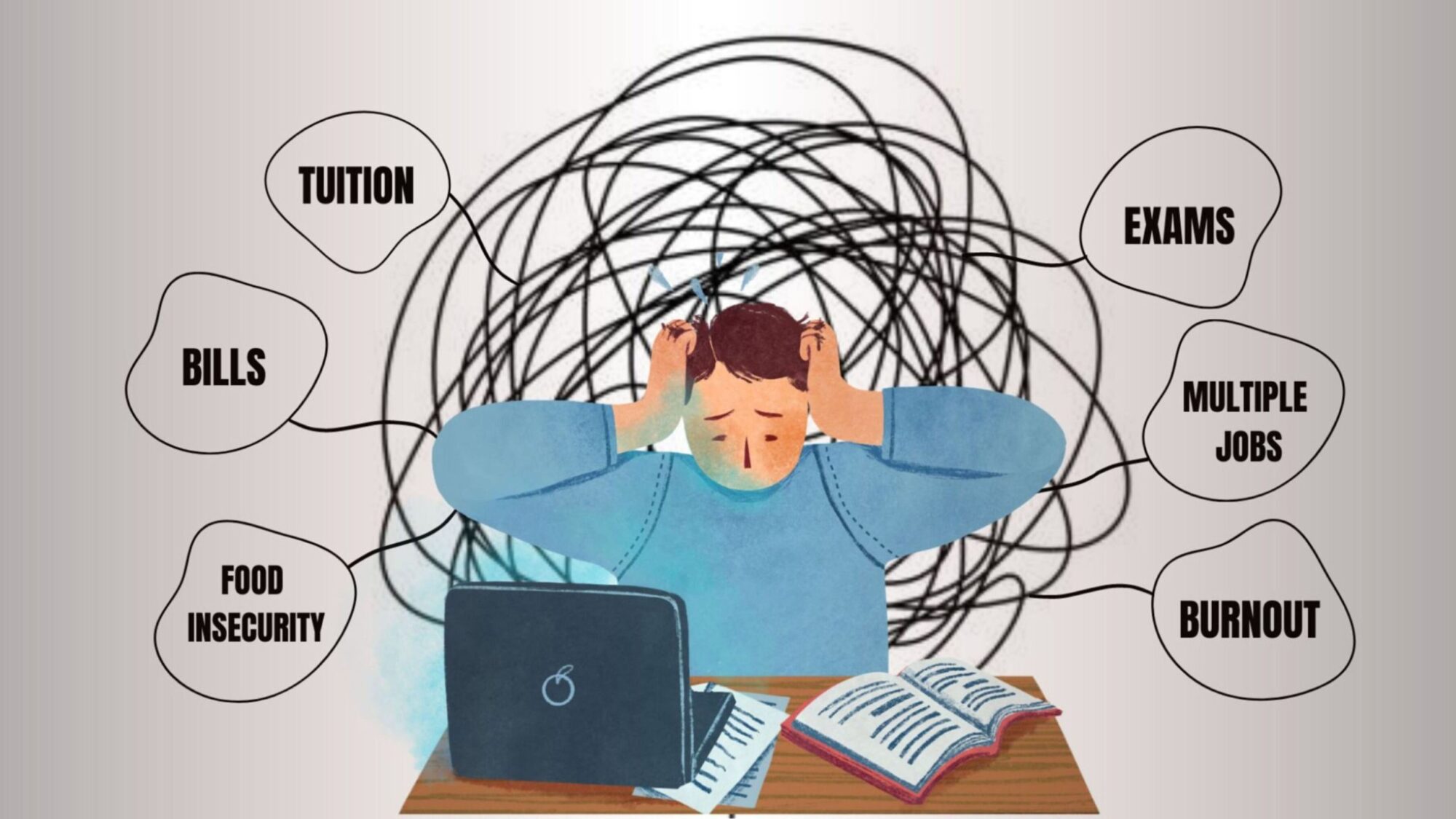

caption

University students face can wait times, stigma and inaccessible services

According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada, 1.2 million children and youth in this country have mental illnesses, but fewer than 20 per cent receive proper treatment.

Multiple barriers stop university students from receiving mental health care. The top barriers are long wait times, stigma, quality of the services, and not knowing how to access services. This is according to a study conducted in 2021 by Abacus Data, a Canadian research and strategy firm, with the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) and the Canadian Alliance Student Association (CASA). MHCC aims to improve mental health systems in Canada, and CASA is an organization advocating for post-secondary students to the federal government.

The study also found that COVID negatively impacted three-quarters of students’ mental health. While mental health services exist, most students believe that it’s of almost no use to seek help.

Time for change

Members of CASA wanted to fill the holes in university mental health services by advocating to the federal government. In November 2022 eight members of CASA, including secretary Kyle Cook, flew to Ottawa.

Cook is in his fifth year of a Bachelor of Arts degree, studying Social Justice and Community Studies at Saint Mary’s University. He is also Vice-President Advocacy of the Saint Mary’s University Student’s Association, and Chair of Students Nova Scotia, which advocates for post-secondary students in the province.

For Cook, working on issues affecting students is an “honourable” position. Cook knew they would be meeting with ministers and senators, but then noticed an in-person meeting with the prime minister. His mouth dropped. The opportunity to share students’ issues directly with the prime minister was a big deal. He was the most nervous he ever felt.

Cook reached the prime minister’s office excited to be part of such an opportunity. His heart was pounding. He temporarily forgot the piling assignments waiting for him back home, and confidently walked forward. The meeting with the prime minister lasted more than 30 minutes. Issues were discussed, research was shared, and problems in mental health services were talked about.

Cook says that even if solutions were not found during that meeting, it was important for the prime minister to know who CASA is, and to listen to what students across Canada want the federal government to do.

Now Cook sits in his office at Saint Mary’s. He wonders when action will be taken, and when the change students need will be seen.

Cook says one issue is “a lack of culturally relevant support for equity-seeking groups on our campus.” He thinks students want to see counsellors who have the same identity as them. “I’m an Indigenous student from Qalipu First Nation,” in Newfoundland, “and I think that if I can receive support from an Elder or an Auntie in Residence, it will be more relevant to my identity.” He wants to see new ways of counselling introduced, ways that make students of all identities feel included. According to Statistics Canada, there were more than 620,000 international students in Canada in 2021. So diverse counselling methods are crucial.

In good shape

Dalhousie is the largest university in Atlantic Canada, with more than 20,000 students. Its students complain about flaws in Dal’s mental health services.

David Pilon is the Director of Counselling and Psychological Services at Dalhousie and has been a psychologist for more than 30 years. He says Dalhousie uses a same day counselling model so that the university can be as responsive as possible to student mental health needs.

“The wait time technically is less than a day,” Pilon says. “It’s not long at all.”

A doctor’s perspective

Sitting in her Toronto office with skyscrapers peeking through slightly open curtains, Joanna Henderson talks about flaws in post-secondary mental health services. “Unmet mental health needs can lead to catastrophic outcomes,” she says.

Henderson, a psychologist with the national Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), specializes in child and youth mental health (ages 12-25). She says most mental illnesses happen – or begin to appear – before 25. One of the main reasons students hesitate to approach mental health services, she says, are barriers. This delays their treatment.

CAMH gathered evidence over the past decade about barriers to accessing mental health services for post-secondary students. Sometimes the barrier comes from within: stigma. But Henderson says most students she treats face stigma from “family members and peers and others.” This makes it hard for them to be open about their mental health issues.

There are also structural barriers. “Our service system [has] not been designed with post-secondary students, or with young people, as co-designers,” Henderson says. Students tell Henderson they don’t feel the services offered meet their needs. They feel alienated in a place where they are supposed to feel comfortable.

caption

No walk-ins are allowed at the Dalhousie Clinic. Students have to book appointments, and be put on waiting lists.Other barriers include not knowing how to access services, wait times that can reach months or years, a mismatch between services offered and services desired, and poor follow-up. When help comes – if it ever does – it’s usually when students are already engulfed in anxiety, stress or depression.

“We need universities to think about how they partner with young people,” Henderson says. “To get a better understanding of young people’s needs, preferences, and solutions. And then we need to act on that.”

While COVID had a negative impact, it shed light on an issue in dire need of assistance. CAMH conducted a study into the university age population every month from April 2020 through August 2022. The study collected data about students with existing mental health difficulties and students without mental health difficulties prior to COVID. The results showed that some students who didn’t have mental health difficulties began to experience them, and the ones who already had mental health illnesses saw an emergence of new difficulties.

caption

Mental health posters at the Dalhousie Student Health and Wellness Centre, hang on the walls.This was because students were suddenly stripped of activities, peer support, connections with the community, sports and extra-curricular activities. They were no longer able to form new relationships with peers and their community, causing them to feel stuck. Henderson says students felt like they had no purpose. Then the world opened up again suddenly and students were expected “to engage and behave in ways that are based on the idea that they had those three years of achieving those developmental milestones.”

Developmental milestones for university students can include moving out of the family home, getting a first job, volunteering, engaging with other youth, and travelling independently.

Now students are trying to catch up, but the feeling of not being able to catch up with society is overpowering. It’s making them seek mental health support. They need support, encouragement, and a place to help them manage their anxiety, stress, and fear.

Multifaceted issue

Christian Fotang, the Vice President External of CASA, says if problems with mental health services aren’t solved there will be “longer term issues” including a backlog of untreated students. “Many things can cause anxiety for students,” says the Vice President External of the University of Alberta Students’ Union. Burnout, trying to keep up with bills, working multiple jobs, food insecurity and the basic pressure of being a university student all pile up.

Cook says the fund was mentioned during CASA’s meeting with the prime minister. He says the federal government wants to make sure the provincial governments would only use the money for what’s intended: hiring more counsellors on campuses. Cook says he believes this could result in the hiring of 1,200 mental health counsellors.

The fund is crucial, in Fotang’s opinion. He asks, if students can’t find help on campus where will they go? The hospitals. Hospitals are already seeing long wait times, so solving campus mental health is also protecting the healthcare system.

Fotang stresses that the federal government needs to properly support students “so they can focus on their education and are less stressed out, less burdened, less anxious.”

Rock bottom

Fotang agrees that stigma is one of the main problems, but stigma doesn’t solve other key issues. “Stigma doesn’t address wait times,” he says.

There need to be more counsellors, more funds for better services and lower tuition, and a better connection between students and services. Fotang says if all the barriers are dissolved, students would be able to get the help they need immediately when needed.

Dealing with stigma is a step forward, and will help students seek help more often. Fotang says most students feel like they can’t admit they need help. Asking for help is a sign of weakness, and they feel the need to put up an “I’m fine” face.

Cook, who regularly talks to students, says that changing people’s idea of mental health services will help get rid of stigma. He says people think that seeking mental health support means “you are at your rock bottom.” But he wants people to understand that seeking counselling is a normal part of taking care of yourself.

“The reality is that… putting time into your mental health is putting time into yourself,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that you are at rock bottom.”

About the author

Sondos Elshafei

Sondos is a fourth-year BJH student at the University of King's College. She has published articles in the Dalhousie Gazette and in magazines....