Studying on empty

caption

A new survey of campus 12 food banks across Canada found 60 per cent of respondents unable to sufficiently feed themselves aside from what the food bank provides.Student hunger in Canada is a serious problem. More research is needed

Before Yas Jawad moved to Wolfville to study at Acadia University, he had never been hungry.

But when he started school, he struggled.

He lived in the residence furthest from meal hall — all the way at the bottom of a hill. In winter, he had difficulty trudging uphill, through the snow after studying.

A lot of the time, he didn’t make it before it closed at 10 p.m. He needed to buy groceries, but couldn’t afford it.

So he did something he never expected he’d have to do — he signed up for an appointment at the Wolfville Area Food Bank.

Now, he is the co-ordinator of the Acadia Food Cupboard, giving food to up to 60 hungry students every week.

Jawad’s student dilemma is not unique and it is not new. A 2021 study by Meal Exchange, a Toronto charity that operated from 1993-2022, found that 56.8 per cent of postsecondary students in Canada face food insecurity — this means they are unable to meet their nutrition needs, or they worry about their ability to meet them.

Student organizers across the country say food bank use is rapidly increasing. Unfortunately, they say, the severity of students’ hunger is not believed – not by potential donors and not by the general public.

New numbers

Food bank volunteer Priya Patel conducted a survey earlier this year of 12 campus food banks across Canada. She did this to give advocates evidence and to help each food bank meet the needs of its students.

Patel finished her masters in epidemiology at the University of Alberta’s School of Public Health in the spring.

While working part-time at the university’s food bank, she wanted to investigate the experiences of university food bank users nationwide. The survey received almost 800 responses.

Across the country, 60 per cent of respondents reported that, aside from what the campus food banks provide, they are unable to feed themselves. Thirty-two per cent reported accessing other food banks.

This is a problem, said Patel. “We’re meant to supplement. Not provide.”

The largest group of food bank users is international students, who were 67 per cent of respondents. The report said 48 per cent of respondents said their campus food bank “never or rarely” carried cultural foods.

Figures like these help campus food banks feed students. For one thing, they might help get funding. Potential donors need evidence of demand to open their wallets.

Patel provided each participating university with statistics on its clients.

This information was helpful for Mauricio Munoz, a biochemistry student in the final year of his degree at the University of Manitoba. He works part time as co-ordinator of the campus food bank.

Without a fridge or freezer, the University of Manitoba Student Food Bank mainly provides non-perishables. The survey allowed Munoz to better meet the needs of students.

“It really helped us a lot,” he said. The food bank swapped canned beans and chickpeas for dry goods. It also increased its vegetarian and vegan options.

Now campus food banks are armed with client data. But this data doesn’t paint a complete picture. For one thing, there’s more people who are hungry who don’t use the food banks.

Missing pieces

Campus food banks, like all food banks, are meant for emergencies. But food insecurity is so common they are no longer used only for emergencies — they are relied on for a chronic need.

Yas Jawad works hard at the Acadia Food Cupboard to get food in bellies. He collaborates with other student societies and throws social theme nights to make getting help less daunting and more cheerful.

Jawad hopes more students can avoid any shame in asking for free food. In fact, he refuses to call the Acadia Food Cupboard a food bank. He says the term might discourage students from using it.

He said he believes students are more likely to access other kinds of support, like social, drop-in, free meal services, because they don’t carry the same stigma as food banks.

It’s the difference between going somewhere that has free food, taking your friends and making a night of it, or making an appointment at a food bank, by yourself, for yourself. That can be intimidating.

Jawad says his most popular initiative is a weekly free meal program called Food Sharing Acadia. It’s an opportunity to chat and hang out with friends over a free lunch or dinner. No appointment is required, and students show up in herds. Over 300 students attend every week. The food supply is usually devoured, with no leftovers.

It is so popular, Jawad and his colleagues set up a meeting with Acadia’s president. Feeding hundreds of students every week was getting expensive — and they needed more money. Jawad said counting the number of meals provided helped make their point and they secured $1,000. But he said he thinks some students are still hesitant to get help.

“I understand first-hand how shameful the experience is,” said Jawad. He is all too familiar with misguided perceptions.

“‘How can you be food insecure while attending a university?’”

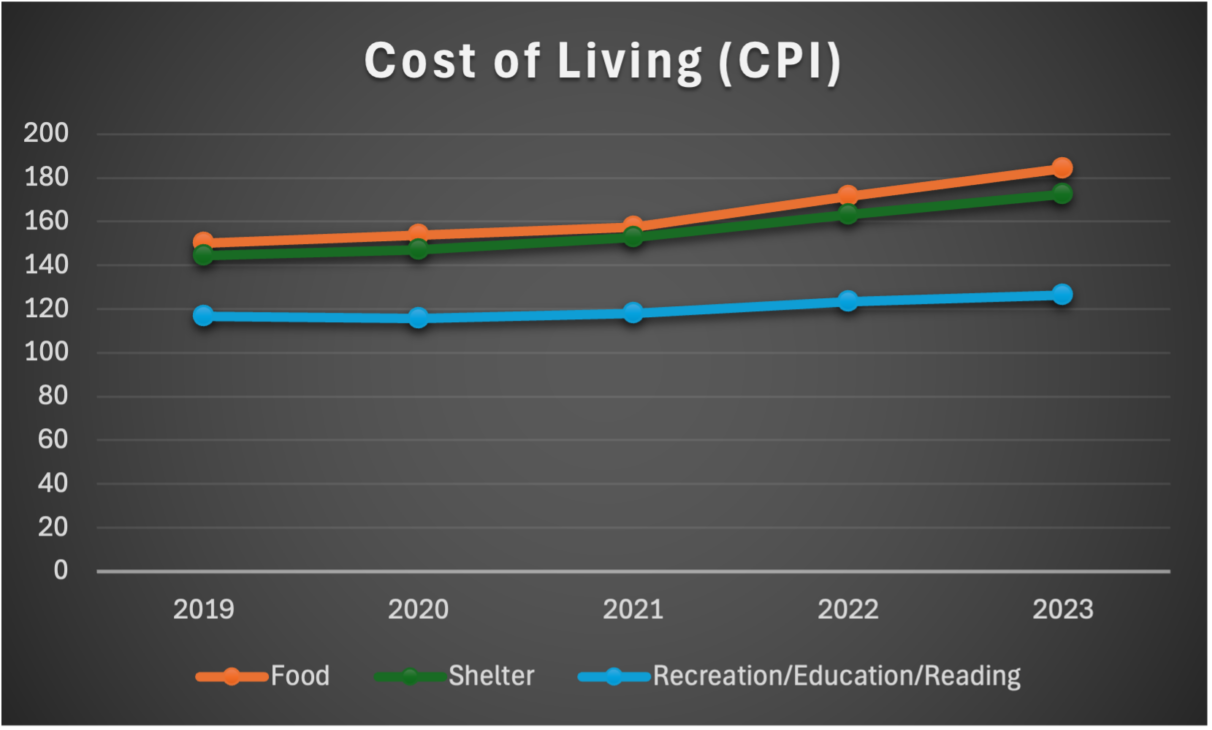

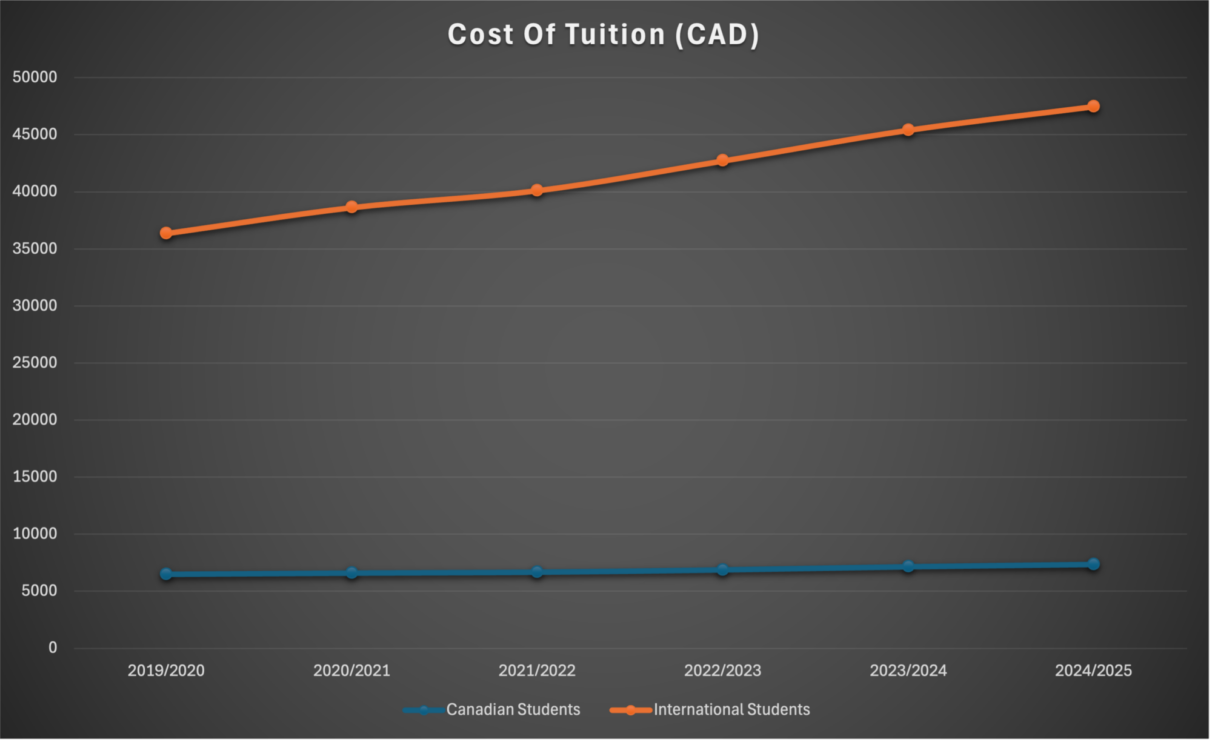

Data: Statistics Canada.

About the author

Olivia Piercey

Olivia Piercey is a fourth year journalism honours student. When not working for The Signal, she can found hosting The Basement Couch on CKDU,...