The chosen few

caption

Why certain graphic photos become iconic – and some don’t

Children running in terror, someone falling to their death, and a toddler’s corpse brought in with the tide. Most people have seen these images: the Napalm Girl, the 9/11 Falling Man and Syrian refugee toddler Alan Kurdi dead on the beach. These photos have been praised and published across the globe as lessons to be learned and moments that cannot be forgotten.

Yet thousands of other graphic images are never presented by mainstream journalism outlets: they are considered to be offensive, brutal, or just unnecessary. This raises an important question. What considerations must be applied to graphic imagery for photos to be accepted by journalistic standards of decency?

Past to present

Death has always been newsworthy. In his 2010 book Representing Death in the News: Journalism, Media and Mortality, Folker Hanusch, a professor of journalism at the University of Vienna, notes sixteenth and seventeenth century European newspapers told of murders in harrowing detail. In the nineteenth century reports of death were accompanied by drawings, and later photos.

Yet in the early twentieth century death became taboo and faded from conversation. French historian Philippe Aries wrote in his 1974 book Western Attitudes toward Death from the Middle Ages to the Present that people became separated from death because it started happening in hospitals and assisted living facilities, instead of in the home. This coincided with a shift towards avoiding the emotions that come with death. Before the twentieth century, healthy people would take on the burden of the dying’s ordeal to spare them pain, including lying about the seriousness of their condition.

Now there is a want to talk about death again, which is reflected in the West’s news media. Death and other related graphic images are present in a way never seen before, because of new technology including the internet and cell phones.

Journalists have ethics and standards when it comes to publishing graphic imagery. The Globe and Mail’s editorial code of conduct instructs journalists to “be sensitive when seeking or using images of those affected by tragedy or grief.”

Janet Arnold teaches a psychology course on death and dying at Mount Royal University in Calgary. She warns that graphic images in the news can be triggering, especially for those who have experienced death. “A veteran I work with here at Mount Royal, who is a student, will not watch the news or read the papers because he is scared he will see an image that will trigger him.”

Arnold says that journalists should also consider the pain it can cause the family and loved ones of those photographed. “I always worry about the people who are impacted,” she says, “because it can add to the trauma and grief.”

Respect the family

Constable Rob Carver of the Winnipeg Police Service worried that, in 2018, Global News Winnipeg was causing trauma and grief for the loved ones of homicide victim Thelma Krull. “We were looking for the media,” says Carver, who was directly involved, “to respect the family.” Krull disappeared in 2015 while on a walk; she was training for a British Columbia hike.

She never came home.

Hunters found Krull’s remains three years later in woods outside Winnipeg. Global published a picture of the crime scene, including the dead grandmother’s skull.

Carver said the police called Global, asking the station to remove the photo from its website. According to Carver, Global declined to do so, saying it had obscured the photo so it was only visible by choice. The photo was accompanied by a warning of its subject matter and that readers may find it upsetting.

The Winnipeg Police tweeted that Global hadn’t removed the photo despite its request. Comments from locals flooded in, with almost everyone echoing the police’s belief that the photo was insensitive and should be taken down.

Global Winnipeg was contacted for this article and declined to comment. The photo no longer appears on its website.

The people of Winnipeg have been deeply impacted by the case of Krull, Carver believes, not only because she was a local woman, but because to this day no arrest has been made. Carver says neighbours have told him that when going for walks now, two years later, they are still worried.

South of the border, in Boston, tragedy also left a community shaken. On April 15, 2013, two bombs detonated 12 seconds apart near the finish line of the Boston Marathon.

John Tlumacki took photos of the aftermath. “I can’t think of any other way to put it,” he says, “besides that people were blown up.”

A journalist with the Boston Globe, Tlumacki says that for years it was hard to live with the pictures he took because the subject matter was so haunting. Still, he says, the close-knit community of survivors was grateful for the coverage he helped provide. “I personally probably got about 500 emails saying thank you.”

Tlumacki says that because the attack was so sudden, seeing photos helped many victims heal. One woman who didn’t get to see the condition of her legs before they were amputated, often asks to see his photos of her from that day. Tlumacki now knows or has met most of the injured people he photographed.

Certain photos from that day, though, he did not publish.

“There are photos I will never let anyone see of Krystle Campbell, who I saw die. It was just so horrific to see her,” says Tlumacki. “I won’t let people see those photos.”

Building distrust

The January 2019 Riverside terrorist attack in Nairobi, Kenya, left 21 civilians dead. The Somali Islamist militant group Al-Shabaab stormed a luxury hotel on Jan. 15, and the bombing and shooting didn’t end until the next day.

The New York Times published an Associated Press photo showing dead bodies slumped over restaurant tables. The decision to publish the photo received heavy backlash.

“To show the bodies lying there, with blood splattered all over…,” says journalism professor Dr George Ogola of the University of Central Lancashire, “the photograph should not have been used.” The photo was published while the attack was still ongoing.

The photo’s publication contributed to Kenyans’ already frayed trust in foreign coverage of Africa, says Ogola. He believes many Africans have a negative view of Western media’s portrayal of the continent and that the photo’s publication “confirmed those fears.” Companies like the Times, says Ogola, have an important role in communicating international events, especially for countries lacking freedom of the press.

Ogola believes most it is most likely that the Times knows it made a mistake. If the choice was done unconsciously, he believes, it’s because of institutionalized newsroom practices that treat victims in distant places differently than locals.

Asked to respond to this criticism, Eileen Murphy, the Times’ senior VP of communications, pointed to a January 2019 article in the paper. It said part of journalists’ role is to document the impact of violence, and if the Times didn’t publish photos showing brutality, it would contribute to “obscuring the effects of violence.” The article also cited two examples when the Times did show American victims of crime and terror attacks: the Los Vegas shooting and the Oklahoma City bombing.

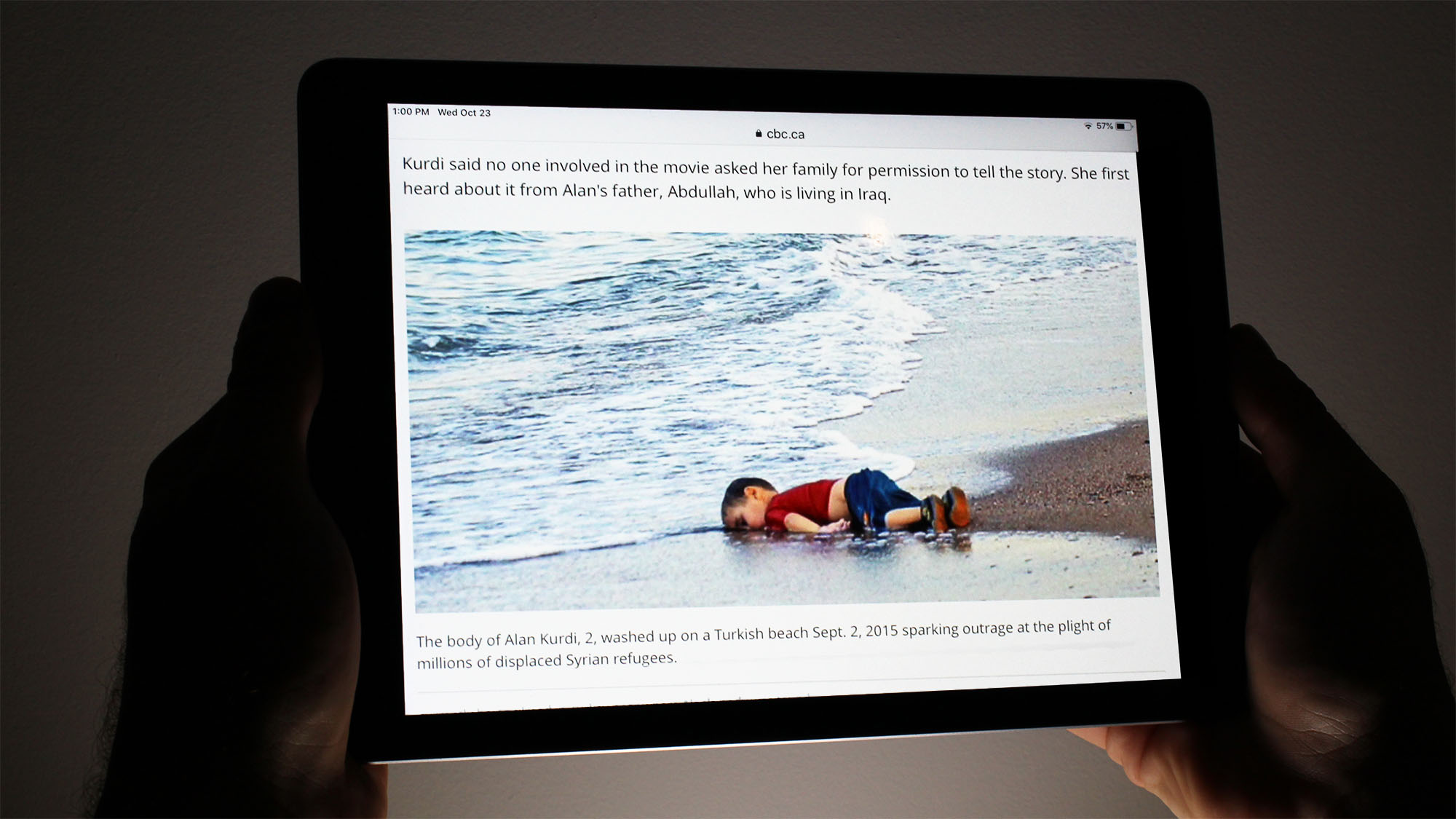

The photo of Alan Kurdi, the Syrian toddler found dead on a Turkish beach in 2015, raised an outcry about the plight of immigrants. His mother and brother, who also drowned, and his father, were also fleeing Syria in an attempt to reach Greece.

If a newsroom’s intention is to provoke a similar outcry, then Ogola believes publishing graphic images is justifiable. The Kurdi photo, he said, meant “Europe suddenly woke up to the reality of what was really going on. You cannot possibly say the same of what happened after the Nairobi attack.”

Alan Kurdi’s photo is one of the latest graphic images that will be remembered for a long time. The photo of the little boy, in his bright red shirt, went viral. Within 12 hours of the image being published a staggering amount of people had seen it – 20 million. The Swedish Red Cross saw donations increase 100-fold in the week after his death, and countries including Canada and Germany vowed to resettle more Syrian refugees inside their borders.

Kurdi’s aunt has been quoted saying that she is proud of the photo because of the good she believes it has accomplished.

Dan Williams, a photojournalism professor at Loyalist College in Belleville, Ontario, believes the photo’s widespread impact is due to something that many iconic graphic images have in common. “Some of the most impactful images we have are not just graphic, but they are also of children,” says Williams. “Those are the images that resonate.”

Element of hope

Iconic graphic images also have this in common: they give people the sense that change is needed – and possible. Yet for this to happen, the people most affected must be inspired by the photo.

The people of Nairobi felt that the picture the New York Times posted was insensitive, while Tlumacki and the Boston Globe told the story Boston wanted, while respecting that the city had gone through a tragedy.

When a graphic image brings hope to those struck by horror, it can help inspire people across the globe to make positive change. It may also have people believe in a future where there will be fewer graphic images to love or hate.

About the author

Olivia Malley

Hailing from Dartmouth Nova Scotia, Olivia is a journalist passionate about the HRM. Outside of reporting she enjoys singing in King's a capella...