The evolution of science journalism

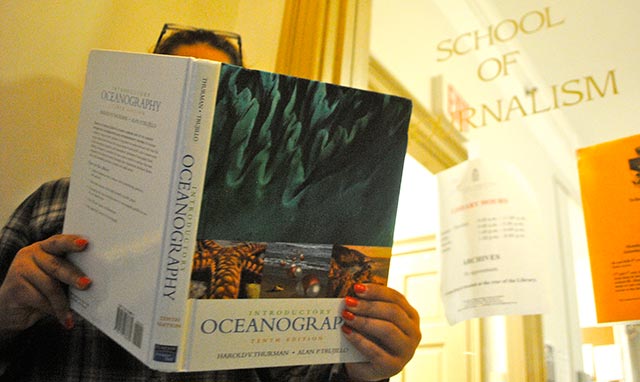

caption

Science is fundamental for writing some stories properly.Facing cutbacks in mainstream journalism, science moves online

Mary Anne White, a materials science researcher at Dalhousie University, shuffles papers on her desk picking up a printed copy of a story written for CBC News. The headline read: Truck carrying toxic cargo cleared after flipping.

“I heard it before I came into work, and it kept saying ‘toxic,’ ‘toxic’ and I was wondering, what has flipped? What was in this truck? Because I’m a chemist and I want to know,” says White, who occasionally goes on the air at CBC Radio to answer the public’s scientific questions.

When White arrived at her office diving into the article she noticed the reporter described acetone, oxygen and nitrogen as highly flammable gases.

“Acetone is not a gas, acetone is like fingernail polish remover, it’s a liquid and it is flammable,” says White. “Oxygen and nitrogen are not flammable, air is oxygen and nitrogen, air does not spontaneously burst into flames.”

The story had no author listed, but there was a time when a science journalist might have written or, at least, edited it. Scientific information has never been as widely available online as it is now, and blogs have become an important news source for audiences. But in recent years, as traditional media declines, science writers are losing jobs, meaning the public is not getting enough quality science news.

“North American newspapers have just been bleeding science writers,” says Jim Handman, senior producer of Quirks & Quarks, the popular CBC radio program and podcast.

In January 2013, the Columbia Journalism Review released statistics about trends in science writing. In 1989, 95 weekly science sections existed in American newspapers. By 2012, the number of science sections had decreased to 19.

Handman’s been with the CBC for 30 years, and with Quirks & Quarks for 15. He explains how, before the Internet, people’s primary access to science information was through local newspapers. With the explosion of the World Wide Web, public access to information increased, and suddenly articles from any newspaper in the world were free. People no longer had to rely exclusively on their local newspaper’s science section.

A few years after public access increased, newspapers started contracting and there were massive layoffs and buyouts. The first people bought out were the senior and highly-paid specialist reporters.

“If you’re running a newspaper, you’re sure not going to get rid of your sports reporter, you’re going to get rid of your science writer first,” says Handman.

Although the Columbia Journalism Review uses statistics from the USA, there is evidence Canada is also losing science writers.

“I worry that as science disappears from the mainstream media that the average citizen will not have the knowledge base that is necessary to make informed decisions in a democracy,” says Handman, “ I want to reach people who aren’t naturally interested in science, who don’t have a science background, who don’t have a science degree.”

In January 2013, Lisa Willemse, a Canadian science writer and the director of communications for the Stem Cell Network, attended the Science Online Conference in North Carolina.The Stem Cell Network is a project bringing together scientists to work on furthering stem cell research. “I sat in on a session that talked about science communication where there is no science communication,” says Willemse, “and the case study that they presented was Canada.”

North American newspapers have just been bleeding science writersJim Handman, radio producer

Willemse explains that in Canada’s mainstream media there is “no newspaper that dedicates a science section,” only a handful of science based magazines, the Nature of Things on television, and Quirks & Quarks on the radio. As a result, Canada imports a lot of its science news from the US, and not surprisingly, US news outlets generally don’t cover Canadian science unless it’s a groundbreaking discovery. “Broadly speaking, their argument was that Canada was a place devoid of science communications,” says Willemse.

Wealth of information

Scientific information is declining from traditional North American media outlets. A wealth of science information exists in blogs; the trouble is you have to look for it.

Many blogs, like the Signals Blog Willemse created as an offshoot from the Stem Cell Network, have been popping up to add to the cache of information on the Web.

Willemse says the decision to start the blog came simultaneously with the choice to abandon their paper newsletter. Deciding to head online in order to “respond more quickly to current events and be more topical,” says Willemse.

The Stem Cell Network encourages its researchers and trainees to contribute to the blog as a way to engage PhD and post-doc students and increase access to information about what is happening in the lab. Simultaneously, the blog gives researchers the opportunity to learn how to write for the public, which is becoming a valued skill in science.

“Researchers are saying that there is less money available, and so if you have to justify your work and you need to get public on board, and supporting science, and science expenditures,” says Willemse, getting their research out there is a good way to do it.

In the past, scientists and journalists have been skeptical of the validity and level of professionalism found on blogs, dismissing them as mere opinions. But that view is slowly changing as more reliable blogs come onto the radar.

Willemse feels science blogs can adapt to changing realities. “People thought blogs were dead five years ago, but they’ve morphed into something that is more credible,” she says.

Dan Weaver, a PhD candidate in the physics department at the University of Toronto, runs a blog called CREATE Arctic Science.

“Blogs are now simply an extension of the research and of our communications and outreach efforts,” says Weaver, “and because of that integrated approach I feel that it’s more credible.

“It helps that you have well known organizations and people that are blogging, and that does really help shift us towards something that people take seriously,” says Weaver.

Even with blogs slowly gaining authority, they are still hard-pressed to attract a general audience.

Richard Zurawski, a Halifax-based meteorologist and author, says that most adults get science information from the nightly newscast. Zurawski is author of a book on how science is portrayed in the media, Media Mediocrity: Waging War Against Science.

Zurawski explains that when he attended the World Conference of Science Journalists, the vast majority of European and Asian science journalists had extensive scientific backgrounds. Including masters degrees and PhDs: these are the people who write about science. “In North America not one person that I spoke to had any never-mind advanced degree, had an undergraduate degree in any of the sciences, or even a few courses in the sciences,” says Zurawski.

One of Canada’s few science radio shows encounters a similar issue on a yearly basis.

When Quirks & Quarks screens journalism students for an internship, they require an intern with not only a journalism degree, but also with a science background. “We’re talking maybe 1000 journalism students across the country,” says Jim Handman, senior producer of the show. “We’re lucky to find one who wants to come and intern at Quarks.”

The Science Media Centre of Canada is trying to change this. Formally opened in September 2010, the centre is a non-profit organization that acts as a resource. It is used by journalists covering scientific topics who do not necessarily have a science background or follow a science beat.

Tyler Irving is a trained chemist turned science writer. He has a background writing for Canadian Chemical News, a Canadian magazine for chemical sciences and engineering. He’s now the centre’s engineering media officer.

One of the centre’s top goals is supporting general reporters who are covering complex scientific issues. “Science is such an incremental field,” says Irving. “It’s always building on years and years of research that has been going on, so when you throw someone into a story, they might not necessarily have the perspective that you’d get from following the field all the time”

The centre also puts heavy emphasis on teaching scientists the skills necessary to communicate their findings with journalists and the general public.

“It’s called Journalism 101,” says Irving. “It’s a course in how journalism works so that when they do get these kind of (media) calls, scientists feel more confident and are more effective in answering those types of questions.”

The centre also offers a ‘Science 101’ course, developed to teach journalists how to tackle scientific writing.

Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax is also trying to adapt to the changing reality. Science journalists may be losing their newspaper jobs, but science writing is a skill increasing in demand.

In spring 2014 Mount Saint Vincent will award seven students the first bachelor of science degrees in science communications. The program is the first of its kind in Canada. “I think our program is the beginning of a trend,” says Barbara Emodi, the coordinator of the science communications program.

Students in the program have the option to major in chemistry, biology or psychology. The rest of their program is in the department of communications, which includes writing, crisis communication and strategic planning.

The program is “breaking the paradigm” of being exclusively an arts student or a science student. It was created “in response to employer demand,” says Emodi.

Innovations such as the Science Media Centre of Canada and the science communications program at Mount Saint Vincent are the upside of this decline in traditional science journalism. But this does not lessen the difficulties faced by journalists covering science stories in this changing environment.

Discovered trends

Pauline Dakin, national health reporter for CBC Halifax, says, “when I started doing this, it was kind of a Renaissance of specialty and beat reporting going on.”

Dakin has been working for on the health beat for the past 20 years. Until recently she was also on the board of the National Science Writers Association.

Dakin sits at her desk in the CBC Halifax headquarters, her framed awards and honours crowding each other as they sit precariously at the top of her shelf.

“In 2004 I was involved in a project on adverse drug reactions,” says Dakin, “I didn’t file any other stories for three months… and we discovered trends that even Health Canada seemed to be unaware of.”

The research on adverse drug reactions became a series that Dakin and her co-authors won national and international awards for.

“I think, in my career, that has been the most rewarding and valuable work that I’ve done in terms of knowing that there has been a huge impact,” says Dakin, “Health Canada did change the way it looked at adverse drug reactions and started being more proactive.”

“(That project) wouldn’t have a hope in hell of happening today,” says Dakin, “because the idea of taking three months to work on something, forget it. Three days is almost impossible.”

It’s a difficult time to be a beat reporter such as Dakin. Keeping the public scientifically informed is an important job.

Back in her office in the Chemistry Building at Dalhousie, Mary Anne White glances out the window. “It’s all part of the bigger picture,” she says. You need to have science “in the public’s mind.” Science is a fundamental background to a lot of stories that are hitting the mainstream, and you need scientifically literate people writing those stories.

“It permeates all our lives,” says White, “whether we like it or not.”