The next step in the evolution of news: Chat apps

caption

Popular messaging platforms no longer just for sexting and selfies

If you roll out of bed and check WhatsApp before you have your first cup of coffee, you’re not alone.

Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr are no longer the kings of social media – and news organizations are beginning to take notice. At the start of 2015, five of the 10 most used social platforms were chat apps, with more users than Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr combined. Instead of solely focusing on “likes” and “tweets,” news organizations around the world are now using trending messaging platforms to spread or gather news, or both.

Chat apps such as WhatsApp, Viber, Line and WeChat are instant messaging platforms that offer users a wide range of sharing options – such as text messages, photos, videos, and short audio – to help people connect in chat groups. They are used worldwide, with WhatsApp, WeChat, and Viber each claiming they have more than 100 million monthly active users. Chat apps are being used in countries all over the world, especially in Asia and Africa, not just as social tools, but also as news-publishing platforms.

News organizations, such as the Globe and Mail, the BBC, and the Huffington Post have taken note of the rise in the use of chat apps. As a result, those organizations are beginning to experiment with chat apps and their features in an effort to reach younger, broader audiences.

Why are chat apps so popular?

Mobile texting platforms have changed with time and technology.

Before 2009, short message service (SMS), also called text messaging, was the leading platform for texting. When chat apps like WhatsApp and Kik were created, their cheap and free texting or calling options became an alternative to the SMS platform that often requires expensive service plans. Users of chat apps only need to have a wireless Internet connection to enable one-on-one or group communication.

With the emergence of social media, Anthony Adornato, an assistant professor of journalism at Ithaca College in Ithaca, N.Y., says, “I think we are now getting used to having one-to-one connections,” which is one of the two underlying trends that are key to the popularity of chat apps. And newsrooms are keen to become more personal with their audiences.

The other key to the popularity of these apps is the users’ desire for greater privacy. Unlike Facebook or Twitter, chat apps can offer a space far from the eyes of family members or employees. Adornato also believes that chat apps don’t have the same level of advertising noise as Facebook or Twitter, which makes messaging platforms appear more trustworthy.

East to west

The invention of messaging platforms originates in Asia, which explains why eastern chat apps, such as WeChat and Line, are ahead in innovation. For example, Line, a Japanese messaging platform, was the first to include stickers in texting to express emotions. These kinds of Asian innovations in features are inspiring western chat apps, such as WhatsApp and Viber, to do the same.

WeChat, which is the most popular messaging platform in China, sets a whole new standard for what chat apps are capable of. It is an app that is not just made for texting; it also contains ten million third-party apps, which allow users to set up medical appointments, shop online and check news. All of these activities are done through a single app that can only be accessed on mobile devices.

Xiang Li, a former journalist in China at the People’s Daily, and a graduate student at the University of King’s College in Halifax, used WeChat when he was a working journalist in China. He learned the strengths of using chat apps for sharing news, which he believes news organizations around the world should be more aware of.

“If news media want to gain more popularity, then they have to put more effort into social media, especially on WeChat, since people are abandoning laptop devices and going for their mobiles,” says Li.

Even with more effort, news outlets still find it challenging to produce content fitting enough for the platforms’ young audiences.

Adornato, who specializes in researching mobile and social media journalism, believes the key for news organizations to reach new audiences on messaging platforms is personalized news content, where users can pick and choose what they’re interested in. But, he says, there is a downside to giving people choice in what kinds of news they wish to get on messaging platforms.

“People will be getting a very narrow view of the world,” he says.

But Li doesn’t think letting users choose their own news is a problem. He believes that the most important thing for any news organization is to gain more audience and more views, even if the news being put on these platforms isn’t serious or politically compelling.

“On WeChat, content should be more about lifestyle and (humour). It shouldn’t be politically driven because the app targets a young audience, and in China the youth don’t like politics very much.”

Trushar Barot, mobile editor for the BBC World Service Group and co-author of the “Guide to Chat Apps” report, which explains the ways news organizations are using chat applications to tell their stories, says chat apps have been slow coming to Canada. Unlike in Asia or Africa, Canada’s short message service (SMS) is already very cheap, which means there isn’t much need for an alternative messaging platform.

But Canada’s Globe and Mail decided to experiment anyway.

The Globe and Mail: the WhatsApp experiment

In October 2015, the Globe and Mail launched a WhatsApp group to keep readers informed about the Canadian election campaign.

The news outlet had noticed that other news organizations in North America and around the world were testing the messaging app. So out of curiosity, Melissa Whetstone, who is the senior social media and communities editor at the Globe and Mail, wanted to know “how many people would sign up to get news this way, whether it was an experience readers would like and if it would turn out to be advantageous.”

The social media team at the Globe and Mail just focused on sharing quick snapshots of information on the candidates’ whereabouts and political promises in one or two messages a day.

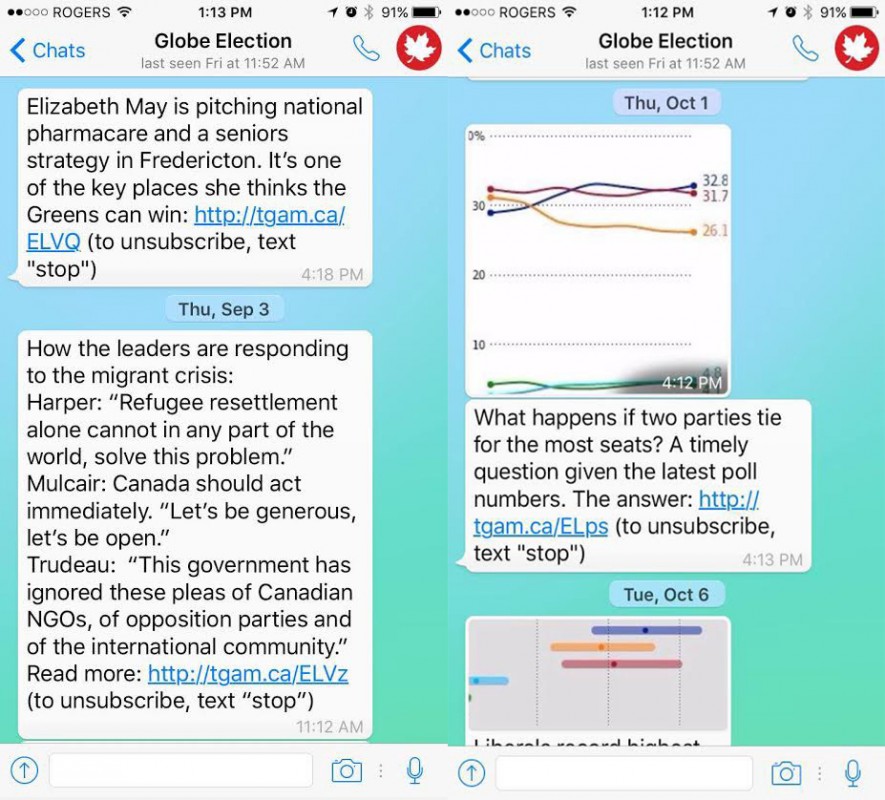

caption

Screenshots from the Globe and Mail’s WhatsApp group, which was created to share news about the Canadian federal election in October 2015.“We had a lot of positive comments, which was a good indication that messaging apps could be a good potential tool in the future,” says Whetstone.

However, using WhatsApp to share news came with exhausting practical and technological challenges.

The Globe and Mail used the “Broadcast List” feature, where users – or in this case a news organization – can send a message to a list that has more than one person. But the process of managing the lists proved to be very time consuming. Broadcast lists have a maximum capacity of 256 people, which meant that the team had to create multiple lists. Whetstone had hoped that she could devote just one hour a day to managing WhatsApp accounts, but that quickly proved wrong.

At the same time, when people decided to opt out by sending a message that said “stop,” the team had to manually look for each contact’s phone number on all six lists to delete it.

“WhatsApp is not designed to broadcast messages to large groups of people, and because we had many lists, it would freeze often,” says Whetstone. “And we had to wait for 30 seconds before sending the next message.”

The app also lacks a built-in analytics capacity that measures audience activity.

“The only thing we could measure was how many people signed up and how many people dropped out, and every link that we shared I added a tracking code on, which I could then use to pull a report,” she adds.

Right now, the Globe and Mail is the only Canadian newspaper at the frontier of using messaging platforms to spread news.

“In its current form it is unlikely that we’d use it in the future,” says Whetstone. But she hopes one day WhatsApp will work with news organizations to make it less frustrating.

But there is one messaging platform doing just that. SnapChat is working in partnership with news publishers by providing a special feature, called Discover, to spread news.

Santiago Tarditi, an international editor at Fusion, an American media company and one of the first partners to join Discover, says “the immediacy of the app and the short attention of the users requires a high level of quality in the way the stories are presented.”

Fusion has a team of five, which includes Tarditi, experimenting with SnapChat. They focus on using custom animation, video and voice-over to tell stories in an interesting visual format. The app even allows users to interact with the news pieces by drawing or adding emojis on them to send to family or friends.

Engaging audiences

Instant messaging platforms are offering some news organizations new ways to engage directly with audiences.

In July 2015, the Huffington Post Entertainment started using Viber Public Chats, a space where one or more people can send messages, to grow closer to its audience.

“We view Viber as a way for readers to see us in a more casual light, and a lot of (Huffington Post writers) in that chat app aren’t writing the most serious of stories,” says Ethan Klapper, global social media editor at the Huffington Post.

The outlet has two Viber Public Chats, a U.S. edition and another English edition, which excludes the U.S. and caters to English speaking countries, such as Canada. Klapper says each has 15,000 subscribers.

“These kinds of emerging platforms have definitely gotten us thinking a lot about how we view the reader or the viewer and how we engage with them,” says Klapper.

He says the company’s large number of subscribers on Viber proves that the platform is worth experimenting with. “And as an early adopter of some of these platforms, we are definitely at an advantageous position.”

At the same time, the Wall Street Journal has been able to build an audience of more than one million subscribers on Line, a Japanese chat app.

“We are just experimenting with what a conversation would look like,” says Carla Zanoni, executive emerging media editor at the Wall Street Journal.

“My very strong feeling about audience development and engagement is that you do not follow the herd,” she says. “It is not like there isn’t, within the journalism community, a pressure to be doing the latest coolest thing, but at the end of the day it is about how we can reach our audience.”

The Wall Street Journal also found a way to get feedback from its Line audience by sending surveys to users. These surveys were sent on multiple platforms, including WhatsApp, to ask readers questions about what kind of stories they were interested in or to get their thoughts on a certain topic.

“We found a robust engagement with these methods,” says Zanoni, who notes that it is challenging to measure audience engagement on messaging platforms that lack built-in analytics.

“I can talk about big follower numbers, but … it is figuring out the right metrics to measure success that is really important,” she says.

Using chat apps to gather news

The BBC has been one of the pioneers in experimenting with chat apps, such as WhatsApp and WeChat. But what makes the outlet so different is that it is not just using them to share news – it is also using them to gather news.

In April 2015, the news outlet launched its Nepal earthquake chat group on Viber, which allowed the BBC to get pictures and videos from users who were directly affected by the earthquake to include in its stories.

As a result, the BBC saw the potential of chat apps as effective tools for sourcing. It pushed the company to change its strategy, especially in the way it used WhatsApp.

“We realized that WhatsApp is really strong when it comes to managing incoming content from people around the world,” says Trushar Barot, the BBC World Service apps editor, “but not in distribution.” That would explain why the Globe and Mail found the app frustrating.

The future

At some point, as predicted in the “Guide to Chat Apps” report, western chat apps will evolve to become like WeChat, which has large numbers of third-party apps dedicated to banking, e-commerce and more.

But one observation on the ever-evolving chat apps is that they are not going away. “Many users are now very comfortable with messaging technology,” says Trushar Barot, the BBC World Service apps editor.

“We learned to be really clear about targeting the right chat app, with the right market, and with the right type of content,” Barot says.