Thriving in the whirlwind of ADHD

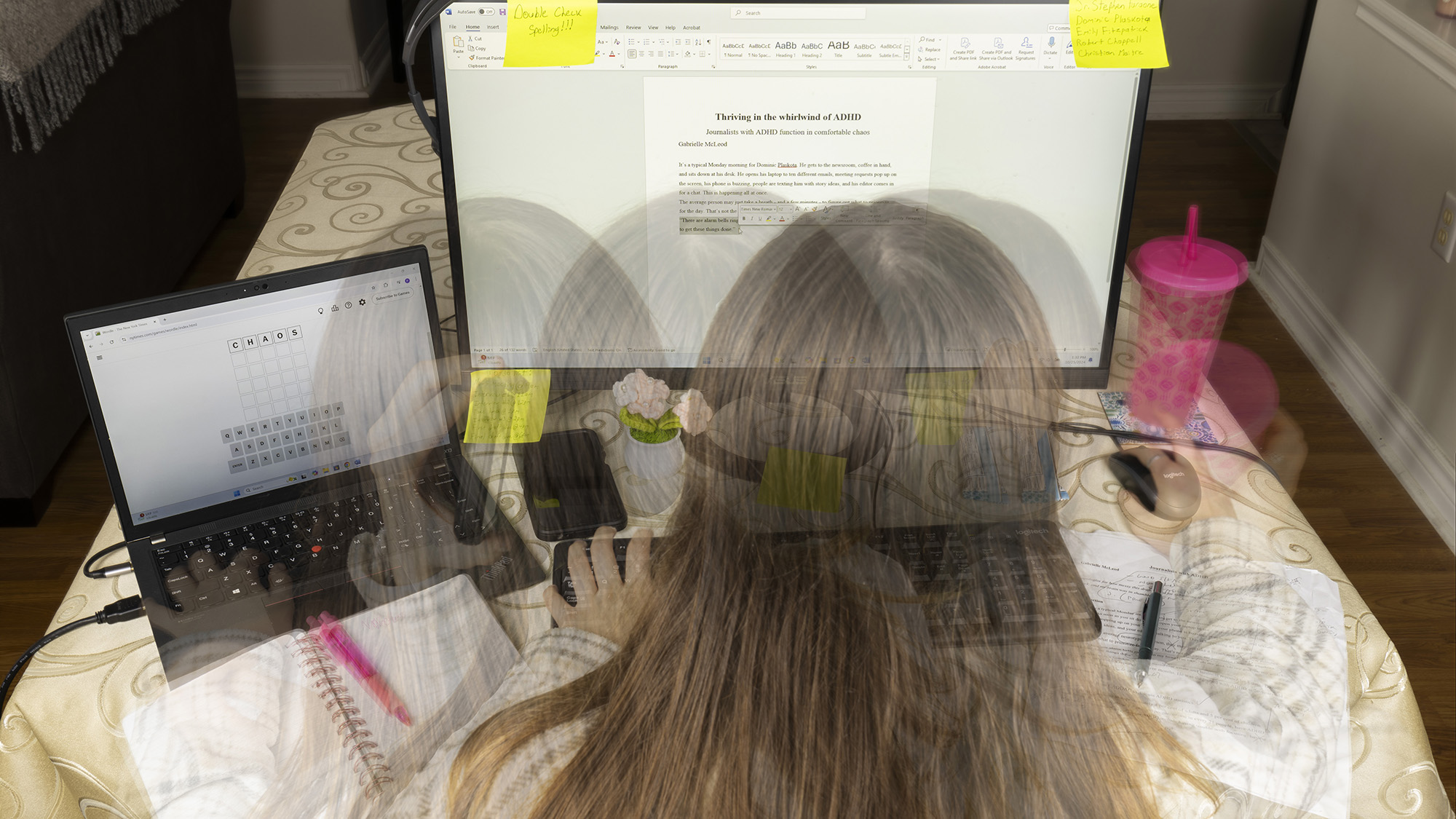

caption

Journalists with ADHD function in comfortable chaos

It’s a typical Monday morning for Dominic Plaskota. He gets to the newsroom, coffee in hand, and sits down at his desk. He opens his laptop to ten different emails, meeting requests pop up on the screen, his phone is buzzing, people are texting him with story ideas, and his editor comes in for a chat. This is happening all at once.

The average person may just take a breath – and a few minutes – to figure out what to prioritize for the day. That’s not the case for Plaskota.

“There are alarm bells ringing in my head. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God!’ I need to get these things done.”

The new ADHD journalist

Plaskota is a London, England, based reporter for Estates Gazette, a real estate newspaper that’s been around for 165 years. He’s only been a reporter for three months. He was diagnosed with ADHD at 20, while in law school.

He got the hint he had ADHD when he was 10 while reading the Percy Jackson & the Olympians series. The books, by Rick Riordan, follow teenager Percy Jackson, a demigod who has ADHD and dyslexia.

“I read those books when I was 10 and was like ‘Oh my God, I’ve got this’. Naturally, I thought, it means I’m hardwired for battle,” said Plaskota. “But my parents didn’t really believe ten-year-old me.”

As a new journalist, Plaskota finds it difficult to prioritize, and to switch between tasks. His team at Estates Gazette has helped him ease into his job, and they check on him often. Every morning, they help him prioritize his day, which teaches him how to build those habits on his own. They have been understanding and flexible with deadlines.

“It can be hard, but luckily, I’ve got a really good team. They’re very compassionate about it. I think it’s one of the benefits of working in a small team,” said Plaskota.

Plaskota says people shouldn’t feel limited by ADHD because you can achieve amazing things. It’s important to be aware of your weaknesses, and what to focus on, so you can reach your full potential.

The working ADHD journalist

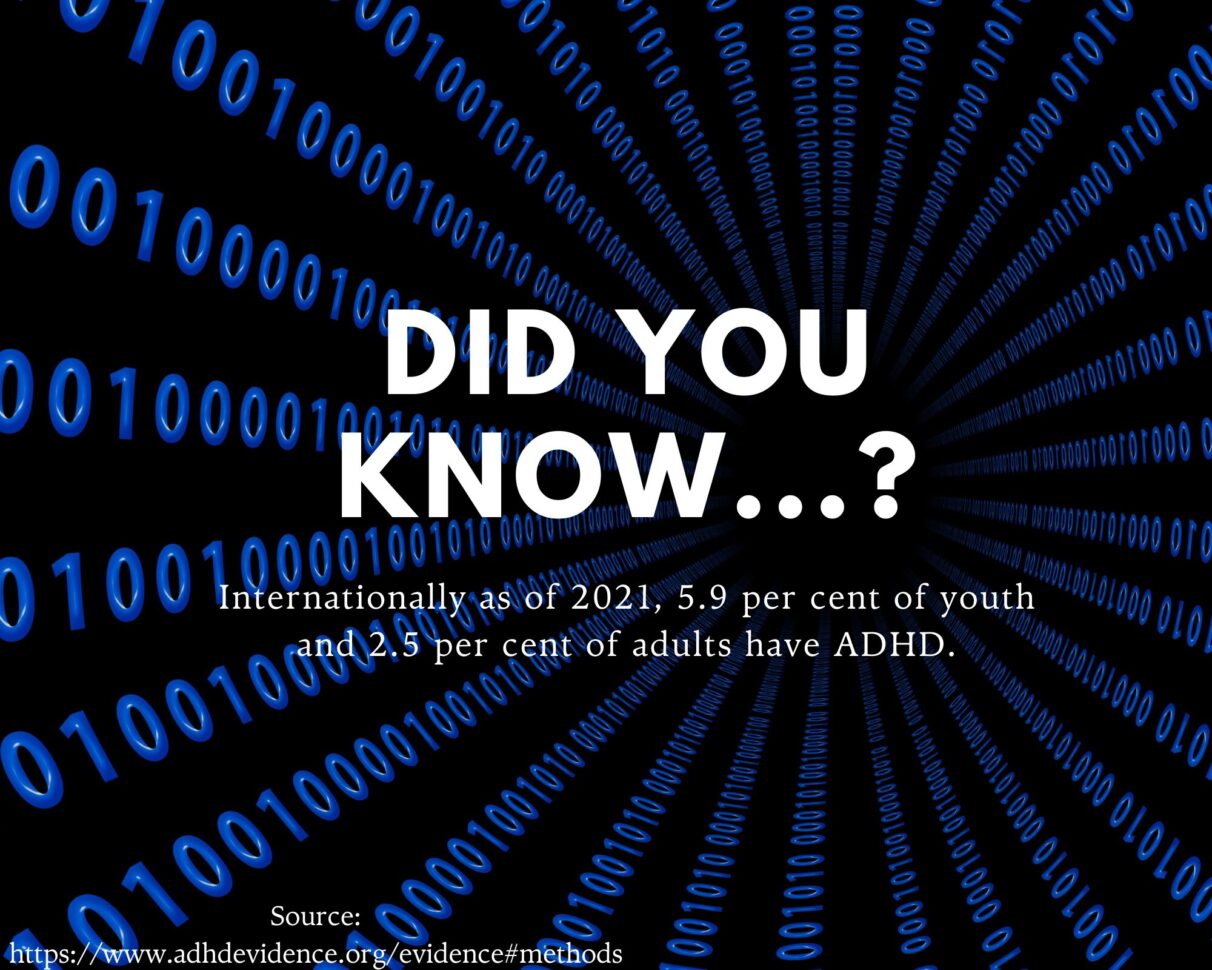

ADHD stands for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In 2021, the World Federation of ADHD released an international consensus statement about the disorder. They found that ADHD exists in 5.9 per cent of youth and 2.5 per cent of adults. Symptoms can include trouble focusing, difficulty regulating emotions, and problems with hyperactivity, organization, procrastination and memory.

ADHD can cause problems that affect a journalist’s job performance. This can lead to lack of motivation and focus, which causes procrastination, getting distracted easily, and having time management difficulties.

Emily Fitzpatrick is a journalist for CBC Edmonton. She was diagnosed with ADHD in 2022, nine years into her CBC career. During the COVID-19 pandemic, she found it hard to self-motivate and get work done while at home. When she returned to the newsroom, she found it overwhelming; that’s when she sought a diagnosis.

“There’d have to be a lot of pep talks of like: ‘Okay, get to work’. Or ‘Okay, you have to finish this now.’ ‘You’re kind of playing with fire right now, waiting or going for lunch instead of getting this done,’ ” said Fitzpatrick.

Sometimes people with ADHD forget things. Fitzpatrick has had moments when she realizes she has made spelling mistakes – especially when something is published with misspelled names – or after an interview, she realizes she forgot to ask a certain question. To prevent this, she has started writing a list of questions she asks no matter what. On paper next to her computer, she has written out the names and titles of the people she’s interviewed. She always double-checks her work.

Fitzpatrick was frustrated when she returned to the newsroom after the pandemic, before she was diagnosed.

“I was like, ‘Oh God, I can’t even focus here. This place is overwhelming. I don’t know how I did this to begin with,’ ” said Fitzpatrick. “So that was a pretty low point because I was like, ‘I wish I could just go home.’ ”

Even now, she will have moments of, “Oh shit, I can’t do my work here and that’s never been an issue before, so what do I do to help myself?”

More recently, if she’s really focused and something isn’t going well technology-wise, she will go to her work’s backroom where it’s quieter.

Since Fitzpatrick received her diagnosis, she finds she’s nicer to herself. It helped her understand why she sometimes looks off into the distance and gets distracted; it helped her understand her brain just a bit more.

“Sometimes you see media reports that are very good, very accurate, [and] helpful to people,” said Faraone. “And sometimes you see reports that are alarmist reports that are trying to get an emotional hook into somebody to read it, as opposed to really presenting evidence.”

Fitzpatrick has noticed that more people are seeking a diagnosis, and more first-person articles are coming out about people getting diagnosed later in life.

“I do think it’s changing from the perception of ‘young, hyperactive child’, but I do think there’s a lot of misrepresentation that hopefully will change as more people talk about it,’ said Fitzpatrick.

How journalists manage ADHD

Christian Maitre, a freelance journalist in Greater Boston, was diagnosed with ADHD at 17 during his senior year of high school. He graduated nine months ago, and now freelances for two non-profit news organizations, the Newton Beacon and Needham Observer.

He says changing his mindset has helped him in his career.

“Very much being kind to myself because I realized a lot of the issues that I have were due to things like impostor syndrome [and] sort of blaming myself for the ADHD when it was kind of an uncontrollable fact that I had this in the first place,” said Maitre.

“So more focusing on how can I change my environment in my external situation so I can allow myself to achieve better success?”

A tip that has helped him is to get into a schedule and to have structure, making sure you stick to your scheduled routine.

Robert Chappell, co-founder of the news website Madison365 in Madison, Wisc., was diagnosed with ADHD in his early twenties. He has adapted to being a journalist with ADHD by understanding his own capacity, saying no to things, and realizing you can’t be perfect all the time.

“It’s a lot of accepting, giving myself grace and acceptance, and not feeling weird about it,” he said.

He also relies on making lots of lists. Having four different notebooks he writes in all the time, everything’s scattered everywhere.

“I’ve accepted that everything’s going to look scattered to an outside person,” Chappell said, “even though I know what’s going on all the time.”

A good career

Is journalism a good career for someone with ADHD? Several journalists interviewed for this story emphatically said yes.

Although there is no data on this, Chappell believes that journalism has a higher proportion of people with ADHD than many other fields. He believes this is because people with ADHD are “so awesome and creative.”

ADHD is “a set of traits that can impede your ability to function as an adult, which is very depressing,” he said. “But also, those same traits can make you really, really smart and creative in certain ways.”

Journalists with ADHD, he believes, can make connections between things that most people can’t make. Often, these can turn into a great story.

“The traits that make it difficult for me to live in the world sometimes also make me a better journalist.”

About the author

Gabrielle McLeod

Gabrielle McLeod is in her fourth and final year of the King's Bachelor of Journalism Honours program. She enjoys feature writing and radio....