Transgender in the news

caption

Sarah RaeMedia coverage of transgender people has improved, but still has a long way to go

Jessica Dempsey didn’t plan to be a transgender advocate, but she says she didn’t have a choice. She was at a dining hall on campus at Halifax’s Dalhousie University in the summer of 2013 when a staff member asked her name. She told him it was Jessica, but he insisted it wasn’t – and then refused to serve her food. She complained to the university, which resulted in staff having to take sensitivity training, but she says that didn’t change anything. One staff member even asked her if her breasts were real. She says the university did little to confront the discrimination until she was featured in an article on CBC online, months after the initial incidents took place. The only way she could be heard, she says, was through the media.

“I didn’t realize what an impact it would have,” she says. “I was just out of options and had to speak out.”

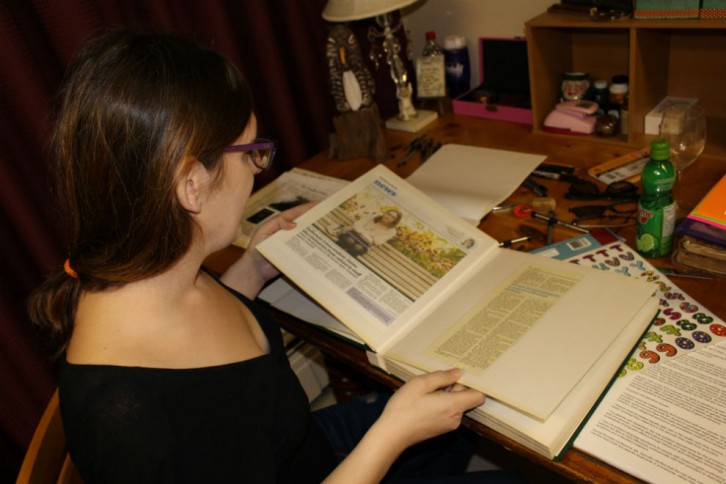

caption

Jessica Dempsey, a transgender student who attended Dalhousie University in Halifax in 2013, flips through a scrapbook of pictures and news clippings about her.After coming out as a transgender woman and then gaining visibility from the news article, she says she felt like “some kind of creature” on campus. Although she had to deal with absurd questions and even threats, a lot of support also came her way as a result of the media attention.

South House, a Halifax-based resource centre that advocates for people “dealing with oppression on the basis of sexuality and gender,” held a “Justice for Jessica” rally on campus in November 2013 and she received emails of support from all over the world. She says students also began to approach her on campus and thank her for speaking up.

Dempsey says she had a good experience with media and was never misgendered, meaning journalists never used the wrong pronouns to refer to her, but she says media outlets generally need to do a better job of covering transgender people. Even in the stories about her, some mistakes were made. The CBC article about her says she was “born a male” and a Maclean’s magazine article that briefly mentioned her referred to her as “transgendered.” The CBC article also says she was staying in a shelter because she felt safe there, when in reality it was because she was homeless and had nowhere else to go. In not mentioning this, the article avoided addressing the homelessness problem transgender people face, she says.

Lack of media coverage

According to a 2011 study by the Williams Institute, a think tank at the University of California law school in Los Angeles, about 1 in 350 adults is transgender. That equals roughly 103,000 Canadians.

Jamie Capuzza, a professor of communications studies and the director of gender studies at the University of Mount Union in Alliance, Ohio, published a study last year that looked at transgender representation in mainstream U.S. news stories. She looked at newspapers published between 2009 and 2013 and found that transgender people had been underrepresented in news media. Even in stories about gender diversity, Capuzza found that non-transgender people often spoke as experts on transgender issues, rather than giving transgender people the chance to speak about their own experiences. She also found that non-binary, or genderqueer, people were even more underrepresented, as news sources chose to highlight transgender people who aligned themselves with either a masculine or feminine identity. She wrote that the media had formed a narrow definition of acceptable gender diversity, so transgender people had to conform if they wanted media coverage. Capuzza says the quantity of stories about transgender people has definitely gone up since the study was completed, but not necessarily the quality.

‘Transgender tipping point’

Since the 1950s, when Christine Jorgensen – a member of the U.S. military and the first known American to undergo sex reassignment surgery – returned from Denmark after her transition, the media has been interested in transgender people, but in a way that is often seen as entertainment, rather than as the subject of serious discussion.

But transgender awareness has taken off in the last couple of years, with Time magazine declaring a “transgender tipping point” in the June 2014 issue, calling it “America’s next civil rights frontier.” That issue featured the first openly transgender person on the cover, Laverne Cox. She’s one of a few transgender people who’ve become household names, in her case because of her role on Netflix’s Orange is the New Black. She was also the first transgender person to be nominated for an Emmy award, for that role.

The actress has been outspoken about transgender rights and about the way the media covers transgender people. In January 2014, she and transgender model Carmen Carrera were being interviewed by Katie Couric for the ABC television show Katie, when Cox famously shut down Couric’s invasive questions about their genitalia. Cox told Couric: “The preoccupation with transition and surgery objectifies trans people, and then we don’t get to really deal with the real lived experiences. The reality of trans people’s lives is that, so often, we are targets of violence. We experience discrimination disproportionately to the rest of the community. Our unemployment rate is twice the national average. If you are a trans person of color, it’s four times the national average. The homicide rate is highest among trans women. If we focus on transition, we don’t actually get to talk about those things.”

Another story that caused journalists to analyze how they were covering transgender people was the Chelsea Manning story. Manning was arrested for leaking military documents in the U.S., and came out as a transgender woman in 2013. Many media outlets continued to use male pronouns and her former name when reporting on her, even after she specifically stated she wanted to be referred to using female pronouns. The Associated Press was one of those outlets, even though AP’s style guidelines instruct journalists to use a person’s preferred pronouns and name. AP released a statement a few days after reporting that Manning had come out, saying its reporters would use “Chelsea” and female pronouns going forward, and most media outlets followed.

Timeline of some of the major stories about transgender people in news media since 1952:

‘Do better right away’

Capuzza says now that more stories are being told, the media have to be careful not to create one dominant narrative. She says most stories about celebrities like Caitlyn Jenner are “surface level” and do not get into important transgender issues, but she says stories like Jenner’s give journalists the opportunity to dig deeper and start reporting on more serious issues. She commends the media for coming a long way in a relatively short time, and says stories these days are more supportive and sophisticated.

Jude Ashburn, the outreach coordinator for South House, says a part of what South House does is to educate the media about how to report on transgender people. Ashburn is a non-binary transgender person and uses the pronouns “they” and “them.” As outreach coordinator, Ashburn has a lot of contact with the media, and says many reporters have chosen to write around using “they” by avoiding pronouns altogether and just repeating their name every time they’re mentioned. They have also been misgendered in news stories. Making assumptions about which pronouns to use based on the way a person looks or sounds is a huge problem, they say. Ashburn says they have had to contact media outlets to say they’ve been misgendered and to educate the reporter or editor.

“We’re all going to make mistakes,” they say. “The point is, don’t dwell on it. Change it fast and do better right away.”

Ashburn says transgender reporting in Canada leaves a lot to be desired. People should have representation and role models in popular media, they say, because if a young transgender person doesn’t see themselves reflected in the media it affects their sense of self. “How can you be what you don’t see in the world?” they ask. Growing up with few transgender role models and even fewer non-binary ones, they say a wider variety of transgender role models is needed too, “for those of us who don’t relate to Caitlyn Jenner.”

Here are some general tips for language use:

[idealimageslider slug=”dos-and-donts-for-reporting-on-transgender-people”]

Guiding reporters

Capuzza is publishing another study soon, this time focusing on style guides in the U.S. She says many style guides have added sections for reporting on transgender people recently. With these updates, she says, they are doing a good job of explaining terms and pronouns and clarifying which words to avoid, and journalists seem to be following along.

James McCarten, the editor of the Canadian Press Stylebook and CP’s Ottawa news editor, says in editing style guidelines it can be difficult to find a balance between enabling reporters to accurately and clearly tell a story, and being sensitive to what is acceptable language. He says he tries to keep an eye on how language and terms are evolving and what the general public finds acceptable, but style editors have to be careful about making too many changes. If changes in style guidelines happen too often, he says, it can confuse reporters and the audience.

With a new style guide coming out by the end of 2016, McCarten says one change being discussed is whether to say it’s explicitly okay to use “they” as an individual’s pronoun. He says the “grammar violation” might be tolerable for the sake of a person’s preference and he personally is increasingly in support of it.

In terms of guidelines for his reporters, Ron Waksman, the senior director of online current affairs and editorial standards and practices at Global News nationally says Global tries to avoid blanket policies because language is constantly changing, but one overriding guideline is to use names and pronouns consistent with what the subject prefers. Back when Chelsea Manning came out as transgender, he says, there were discussions in the newsroom and notes were sent to reporters about preferred pronouns and names, following AP’s example. He says generally reporters know they have a resource in him or in their news directors if they are unsure about anything.

Jack Nagler, the director of journalistic public accountability and engagement at CBC news, says there has definitely been an increase in coverage of transgender issues, along with an increase in public interest. He says CBC hasn’t had any major policy changes with regard to covering transgender people, just a heightened awareness of and sensitivity towards the issues. He says one of the principle guidelines reporters and editors act on is to respect the subject of the story, so they will use the pronouns and terms the subject prefers. An overriding issue in any story though, he says, is clarity for the audience, so if an explanation is needed or it’s easier to work around something, a reporter may do so to avoid confusing the audience.

Nagler says that whether or not the media is doing an adequate job of reporting on transgender people is for the community to say, but he says the media is definitely doing a much better job than in the past. “We’re paying more attention, we have more understanding, we show more respect, we’re giving more profile to the issues and doing so in a way that as often as possible is helping people to understand things,” he says.

Telling better stories

Ashburn says there is a “massive wave of change” happening right now and while there is little representation of transgender people in mainstream media, it’s also the age of mass representation through social media, where transgender people are connecting and educating like never before.

This is the time, they say, for marginalised people to tell their stories.

“There are better stories that need to be told, and they need to be told with dignity, and they need to be told properly.”