We’ve been here before: demystifying AI’s threat to journalistic integrity

caption

Accuracy in photojournalism has become even more important with the rise of AI-generated imagesPhotoshop was once seen as a danger to accuracy in photojournalism. How can we look back at the past to better grasp the present?

In February 1990, Today show host Deborah Norville was introducing a segment on the NBC morning show about the debut of a new graphic-design tool: Photoshop.

“A picture may no longer be worth a thousand words,” said Norville.

“These days, the picture that the camera takes may well not be the picture we end up seeing in newspapers and magazines,” Norville continues. “Technology makes it difficult, maybe even impossible, to tell what’s real and what’s not.”

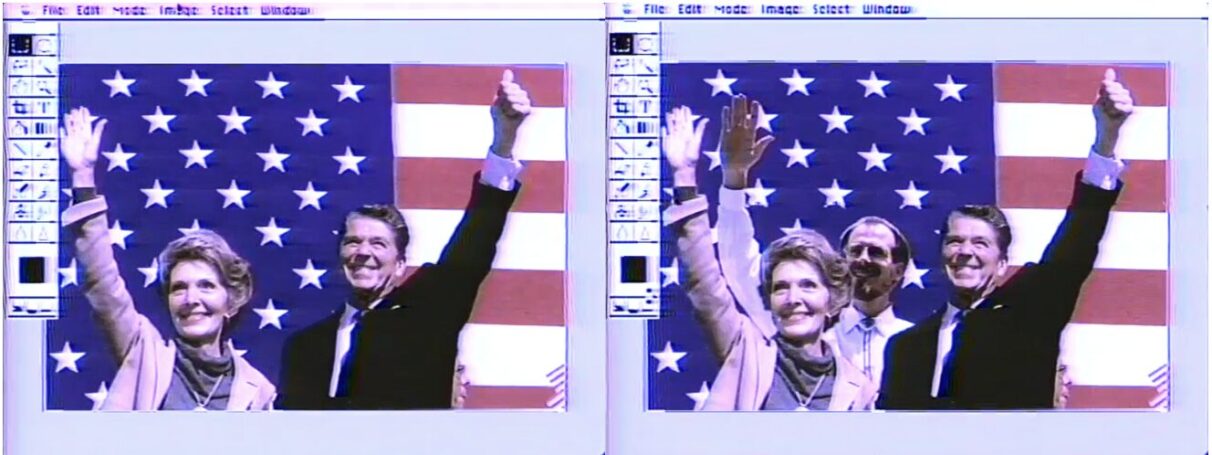

Beside the host sits Russell Preston Brown, senior art director of Adobe Systems, as he fiddles with a Macintosh II computer and uses Photoshop 1.0 to insert an image of himself into a photo with ex-president Ronald Reagan and first lady Nancy Reagan, the three of them now joined in a celebratory salute in front of the American flag. Brown, while asserting that he uses the tool ethically in his professional life, acknowledges his TV demonstration is a “most unethical situation.”

caption

Left: A photo of Ronald and Nancy Reagan being put into Photoshop to be edited live on the Today Show in 1990. Right: Russell Preston Brown inserts himself into the photo with Ronald and Nancy Reagan using Photoshop.Next to Norville sits Fred Ritchin, author of the book In Our Own Image: The Coming Revolution in Photography, also released in 1990, warning of the dangers of photo manipulation.

“Well, the thing is that photographs we still tend to believe as a society,” he told Norville. “If an eyewitness says they saw something we might say ‘maybe they’re wrong,’ maybe a government denies it, it’s one person’s word against another. But when you see a photograph, you really tend to believe that something happened.”

Thirty-five years later, the threat that AI poses to photographic reality is alarming to many in journalism, but the 35-year-old Photoshop segment indicates that doctoring images is nothing new. And even before Photoshop, photographers could distort images in the darkroom. The tools have been at their disposal for decades, and some who abused their powers paid a heavy price.

In 2003, The Los Angeles Times fired photographer Brian Walski after he used two separate images he had taken during the war in Iraq to make a composite that he thought made for a stronger visual. This slight skew of reality was enough to get Walski terminated and essentially blacklisted as a photojournalist.

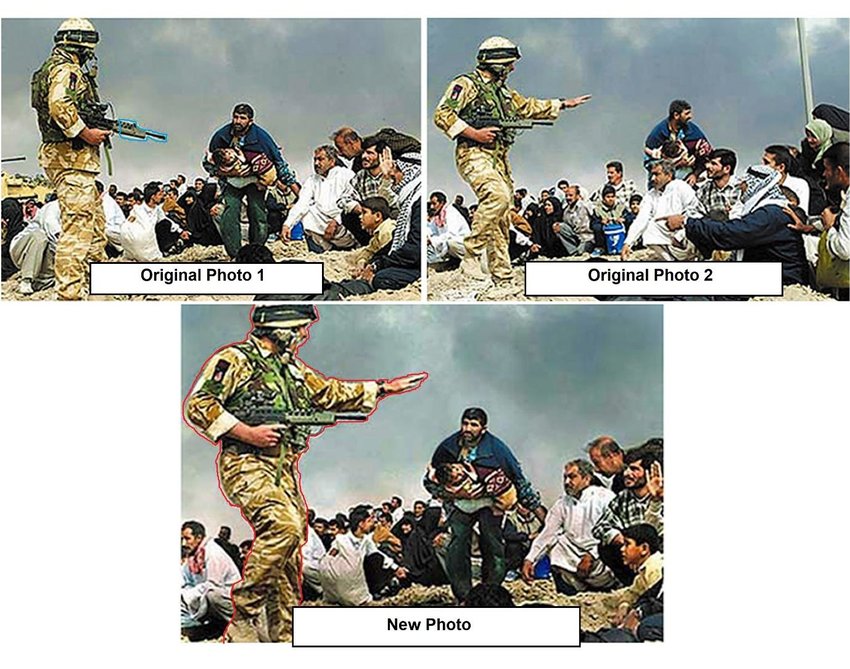

caption

The two photos Brian Walski edited together, compared to the composite published by the L.A. Times.Adnan Hajj, a freelance photographer working for Reuters, used Photoshop to digitally alter a photo of the aftermath of an attack in Beirut during the 2006 Lebanon war, adding and darkening smoke to make the damage appear worse than it was.

caption

Left: Adnan Hajj’s original photo showcasing the aftermath of an attack in Beirut. Right: Adnan Hajj’s edited photo of the aftermath of an attack in Beirut. The smoke has been digitally-altered to appear darker, exaggerating the amount of smoke from the original photo.Later, Hajj was also found to have edited a photo of an Israeli fighter jet, cloning one singular flare into three that he misidentified as missiles. This resulted in Reuters parting ways with Hajj and pulling all of his photos from their site.

caption

Adnan Hajj’s edited photo of an Israeli fighter jet, shown here firing three flares he misidentified as missiles. In the original photo, there was only one flare deployed.Technology has evolved to the point where any user can create photo-realistic images, without leaving their home or office, using typewritten or verbal commands known as prompts. The images are often composites of real photos.

The role of a photojournalist is simple, but it’s important. They take photos that tell stories, but it is imperative that those photos depict the truth. They capture real life through their lens, making sure to present things as they actually happened. With the ever-increasing presence of generative AI in our daily lives, where it seems anyone and everyone has the power to manipulate reality at the push of a button, veteran photojournalists told The Signal there is an increased need for journalistic integrity in a world of fake images.

“It’s important work, and it has to be done with dignity and respect,” said Andrew Vaughan, hands waving, sitting on a chair beside a stack of photography books in his living room in Dartmouth. Vaughan, a retired photojournalist who worked at the Canadian Press for over 36 years, says the work of a photojournalist is something that should never be replaced by the emergence of artificial intelligence.

“I fear for the future of photojournalism if somehow AI got their foot right in the door.”

caption

Andrew Vaughan poses for a photo outside his home in Dartmouth. Vaughan was a photojournalist with the Canadian Press for 36 years.In 2024, Reuters’ annual Digital News Report found that people had a strong aversion to AI being used to generate photos in the news. The report stated: “(Respondents) are strongly opposed to the use of AI for creating realistic-looking photographs and especially video, even if disclosed.”

In Reuters’ 2025 Generative AI and News Report, it was revealed that respondents were somewhat comfortable with journalists using AI to assist with things like editing spelling and grammar, in which 55 per cent said they were comfortable, and translation, in which 53 per cent said they were comfortable. Respondents were significantly less comfortable, however, with the idea of journalists using AI to create realistic-looking images, with just 26 per cent claiming to be comfortable.

Audience trust is something Steve Russell, a decorated photojournalist for the Toronto Star, understood in 2019 when he gave an impassioned TED talk at the University of Toronto Scarborough about the importance of integrity in photojournalism.

Trying to keep his composure and not get “too hyped up,” Russell spoke out to the auditorium, under the hot lights, trying his best to remember his talking points. No teleprompter. He had written cues on his hand but when he looked down he saw the ink smudged, the words faded away by his sweaty palms. Regardless, he powered through, giving a lecture bolstered by one singular line:

“If people don’t believe what I photographed is the truth, then, you know, where is photojournalism? Where is journalism as a whole?”

It’s a sentiment that has become all the more relevant with the arrival of generative AI. In a phone interview with The Signal, Russell remained steadfast in his disapproval of manipulated photographs in journalism, saying nothing can replicate the impact of a real image.

“I think it’s one of the most important things because it gives you an instant visual and emotional reaction to things,” he said. “If we think about world events and these things that define us, it’s usually a picture. You know, it’s (Robert) Capa’s picture of the guy on D-Day in the water, it’s the picture of the napalm girl; it’s all these little moments that like, when you think about that moment, you think about that picture.

“There’s a reality that AI cannot create, and that’s the moment.”

Not only is it important for photojournalists to capture and portray scenes as they really happened, but journalistic standards and ethical guidelines exist to dissuade them from distorting an image.

The Canadian Press guidelines state the following: “The Canadian Press does not alter the content of photos. Pictures must always tell the truth — what the photographer saw happen. Nothing can damage our credibility more quickly than deliberate untruthfulness.”

Similar guidelines exist for The Associated Press, Reuters, and World Press Photo. Ultimately, it is up to a photojournalist’s publication to implement rules, but generally, manipulating a photo to distort reality is a fireable offence, as it undermines the credibility and integrity of the publication.

Ivor Shapiro, former chair of the ethics committee of the Canadian Association of Journalists, says despite the changing technology, journalistic integrity remains key.

“Ethics is not about just obeying rules,” Shapiro told The Signal. “It’s about thinking critically about what you do, being more creative, and engaging with the complexities of the world today. I think it’s up to people, humans. Journalists are human.”

Machines are not going to ensure journalistic integrity. It is up to photographers to adapt with the times and prove to people that their work can be trusted.

Tim Flach is doing just that. Flach, known for his striking photos of animals, has taken a unique approach to combating AI within his work. After realizing AI had been used to generate photos in his specific style, Flach has gone out of his way to make his photos more difficult to replicate, doing things such as adding extra bits of hair to an image of a cat.

caption

Left: A portrait of a bald eagle taken by Tim Flach for his 2021 book Birds. Right: A portrait of a bald eagle by AI image generator Midjourney using the prompt “Eagle by Tim Flach.”In addition to making his photos harder for AI to copy, Flach has also embedded QR codes into his new photography book Feline, which, when scanned, reveal behind-the-scenes videos and narration from Flach himself, adding an air of authenticity to the photo. The safeguards are important, Flach said in an interview, amid the changing technology.

“We must create a co-existence that is better for our well-being, our health, and understanding of what has really existed,” he said. “We need more transparency at the point of ingestion.”

Transparency and verification will play an important role in photojournalism in the future. One such verification tool being implemented to combat the spread of misinformation and disinformation is C2PA. This can show viewers embedded data within a media file, displaying edits that have been made, or whether or not the photo has been AI-generated or taken by an actual camera.

Bruce MacCormack, one of the founders of C2PA, says people deserve to know the source of the news photo they’re looking at.

“News happens somewhere else and somewhen else,” he told The Signal from London, U.K. “And there’s a lot of technology that interferes between those two points. So, someone that has a good sense of what could happen becomes more skeptical. So this is a way of providing a solid cryptographic link between the where else and when else.”

MacCormack continued: “So what we’re hoping is by providing a strong signal of integrity that we can have the professionally-produced content stand out. You know it’s coming from a source, you know that source is valid. You know they’re not just creating this out of thin air with an AI generator.”

He says while news organizations are actively looking to implement C2PA, it could be a few years until the wider public has access.

For Andrew Vaughan, even with new technology, the core principles of photojournalism will always remain the same.

“From the beginning to the end of my career, my basic work conviction was never changed, even with technological changes,” he said. “There’s no reason for that to change just because AI has shown up. Because all this technology has come and gone, or it’s come and just keeps ascending.”

Back in 1990, in the Today Show studio, photographer and Photoshop skeptic Fred Ritchin raised red flags as he watched Adobe’s art director manipulate the photograph of the Reagans.

“My concern is that if the media takes to doing what Russell is demonstrating now, people, the public, will begin to disbelieve photographs, generally, and it won’t be as effective and powerful a document of social communication as it has been for the last 150 years.”

As the segment ends, host Deborah Norville says: “It’s a frightening possibility,” before adding: “We’ve met the enemy and he may be us.”

The group snickers.

About the author

Jude Pepler

Jude Pepler is a reporter for The Signal and a fourth-year journalism student at the University of King's College.

Leave a Reply