climate change

What climate scientists really want you to know

Local climate experts set the record straight

caption

Christine Stortini says she's surprised some people still think climate change is not real.

caption

Christine Stortini says she’s surprised some people still think climate change is not real.Christine Stortini says it doesn’t make sense that people still believe climate change is fake.

Stortini says she recently encountered a fellow traveler in Europe who believed climate change, also called global warming, was a huge conspiracy. “I was really shocked that that was something someone would think,” she says. Stortini works at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography and is pursuing a PhD at Queen’s University.

“I know people who collect the data; I know where the data is stored,” she says. “To falsify decades of temperature data is impossible, or it seems to me like it would be really difficult at least.”

A survey conducted last fall by the Ontario Science Centre indicated that 85 per cent of Canadians say they understand basic climate science. The same study also found that 40 per cent of Canadians say the science of climate change is unclear or unsettled. Related stories

Climate scientists disagree.

It’s real

Scientist John Loder says climate science is robust, and that inadequate data is not an issue. While there are still questions to answer, it’s not a matter of whether human-caused, also known as anthropogenic, climate change is happening or not.

“As a climate scientist, I’m as confident that there is anthropogenic global warming occurring and that it will continue to occur, as I am that we (had) winter weather and will have summer weather this year,“ says Loder, who started studying climate change in the 1980s at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography. He retired last year.

Since he has studied climate change for decades and has high confidence in the results, Loder finds it frustrating to see the science get misrepresented, maligned or ignored.

And Loder is not the only one who feels this way.

Weather is local

Meteorologist Jim Abraham says when it comes to people’s misunderstandings about climate change, there are many. One thing he wishes was understood is that weather is not the same thing as climate. He says people often confuse their local weather with what’s happening on a global scale.

caption

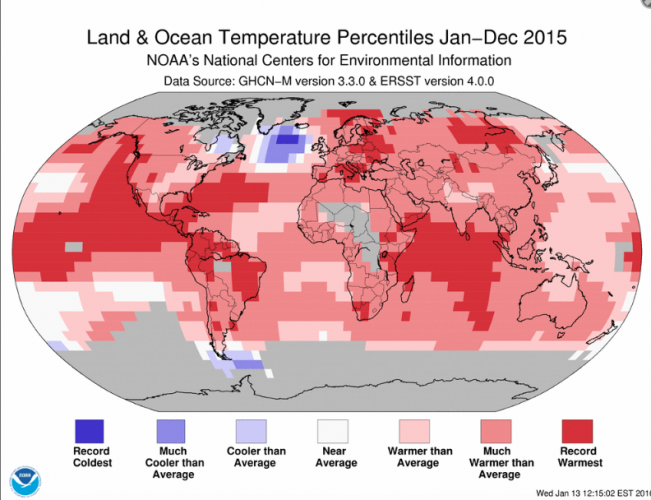

Meteorologist Jim Abraham says climate is not the same as weather.The winter of 2015 is a classic example, says Abraham. When he gives talks on the topic, he likes to show a map of global average temperatures in 2015.

“The whole globe is red, except for a little round circle in eastern North America that’s blue because it’s cold,” he says.

caption

This map by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) shows global temperatures in January to December 2015.2015 was the hottest year on record at the time, but that winter Eastern Canada was blanketed in snow.

“There was no way you could convince anybody here because people were focused on what they were experiencing,” says Abraham. And that, he says, is frustrating.

Glen Lesins, a professor in the department of physics and atmospheric science at Dalhousie University, agrees. It’s a point he makes sure to get across in his climate change class.

“When you have a severe weather event that, by itself, doesn’t tell you anything about climate change. And yet so often you hear people hear this is an example of climate change,” says Lesins, who studies the rising temperatures in the Arctic. “It really isn’t.”

caption

Glen Lesins says temperatures in the Arctic are rising up to twice as fast as elsewhere.One thing that’s often forgotten, adds Abraham, is the impact of warming on northern communities and ecosystems.

“It’s easy for us to say, ‘I hate winter, bring on global warming,’ but not really appreciate the fact that this is a global, extremely important issue that is having a significant impact on people’s livelihoods.”

Species on the move

Stortini has studied marine species’ vulnerability to these changes and how they move in response to warming temperatures.

A question she is often asked is ‘who cares?’

Stortini says people’s livelihoods can depend on one particular species, like a certain type of fish. If that species disappears, it can have huge repercussions on a community.

In addition, a question she finds that is often raised is: if species move northwards, what happens to those in the Arctic? The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) says that climate change will likely cause the loss of entire habitats and species.

caption

Arctic species like the polar bear are facing a rapidly changing climate.We are vulnerable

As humans depend on other species for food, clothing and even clean air and water that leaves our populations vulnerable too.

Abraham says people don’t realize how dependent society is on a stable climate. The entire food system depends on the right kind of weather.

All it takes to affect the movement of goods, he says, is a power outage that lasts a few weeks. When it comes to severe weather that impacts the production of food, it can easily turn into a crisis.

Climate change is a huge threat to food security, but few people realize that, he says.

“Let’s face it, the bulk of the population in western society gets their groceries from the grocery store,” says Abraham. “They don’t have a clue about the end-to-end system of even food production.”

Not going away

Lesins says that most problems tend to go away when a solution is found, but this will not happen with climate change.

“For a number of reasons, we’re going to be stuck with this problem for a very long time,” he says.

He says the longer it takes to address climate change, the worse the changes will be. Even if we stopped emitting greenhouse gases now, we would still experience the impacts of climate change for hundreds of years.

This is because it takes a long time for carbon dioxide to naturally remove itself from the atmosphere, says Lesins.

caption

Burning fossil fuels for energy generation is one way greenhouse gases enter the atmosphere.“You’re talking about messing up the lives of future generations, really,” he says. “I don’t know if people really understand how severe that is.”

For Abraham, when he thinks about what climate change will mean for the future, he worries about his grandchildren, ages two and four.

“If nothing is done, it’s not going to be a pleasant world because it’s not only what happens to the natural system, it’s the conflict that could result,” he says.