Whither Canadian documentary films?

caption

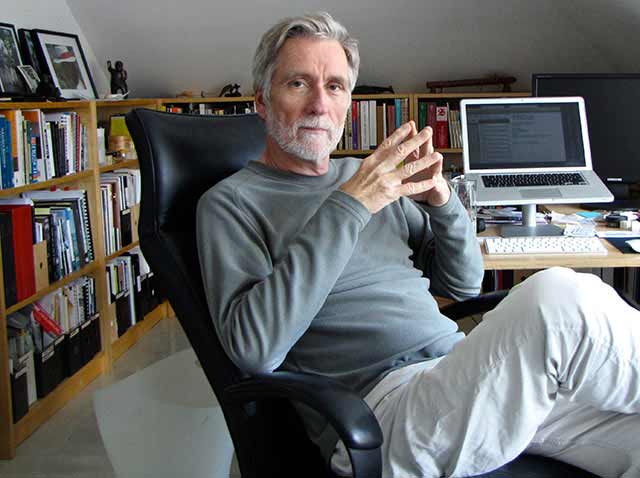

John Walker of Halifax has been making films for 38 years.Funding cuts, industry changes leave doc makers fearful

A young boy with a mop of brown hair sits at a dining room table. On the table’s wooden surface, attracting his stare, rests a heavy stone object: a carving of an Inuk and a polar bear intertwined in a violent embrace.

The art ignited the boy’s imagination.

“I was inspired by art and culture to go north,” says John Walker. “If that piece of carving hadn’t landed on my dining room table would I have gone north? I’m sure I wouldn’t have.”

Walker, a Canadian documentary filmmaker, has worked in the industry for 38 years. This scene is from his latest feature-length film Arctic Defenders, which premiered at the Atlantic Film Festival in September 2013.

Addressing arctic sovereignty issues, the film aims to defend and conserve Inuit culture. Ironically, the documentary form itself – another integral part of Canadian culture – also needs defending. Documentary is struggling to survive.

The growth of the Internet and its global reach has set a time bomb for television. One way this can be seen is in the decline of the traditional documentary.

Documentary filmmakers in Canada face a turbulent time, as funding from television broadcasters continues to decrease. Currently, television broadcasters trigger documentary productions in Canada. All filmmakers need a broadcast licence fee from a broadcast distributor in order for their films to find funding from the private and public sector. Without the licence – or personal wealth – an idea can’t be brought to life.

These fees are steadily decreasing as fewer broadcasters have slots to host documentaries. This is partially the result of consolidation in the sector and a reliance on reality television’s more popular ratings. Trying to integrate itself onto the Internet is a transition for an industry reliant on its television roots.

“Right now, every film I make, I think it might be my last, and that’s the way I operate,” says Walker from his home office in Halifax. Awards and posters from past productions line its walls. “We’re facing the extinction of the feature-length documentary.”

Funding for documentary production decreased by more than $105 million (21 per cent) from 2008 to 2011, according to studies from the Documentary Organization of Canada’s (DOC) June 2013 report Getting Real: An Economic Profile of the Canadian Documentary Production Industry. The projection for feature length films is worse. Over a three-year period, the genre faced an 83 per cent decline in production volume after a loss of $19 million in funding.

“(Documentary) has a bleak future on our television screens,” says Lisa Fitzgibbons, the executive director of the DOC and the commissioner of the report. “The financing is extremely difficult to cobble together, and my view is that something’s got to give.”

Currently 98 per cent of all English-language documentary production, and 87 per cent of all French, is produced for television.

“We have a financing system that speaks to a different era, because it’s predicated on a broadcaster,” says Fitzgibbons. “People are consuming content in so many different ways now that we have to readjust how we fund content in light of how people are consuming it.”

By looking at festival attendance numbers, it’s clear Canadians are still avidly interested in documentary. Toronto’s Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival is the largest of its kind in North America. It is continually coming up with record audiences. In the spring of 2013, it had 180,000 attendees – 15,000 more than the previous year. In 2012, the Montreal International Documentary Festival increased its audience by 33 per cent, doubling its number of paid admissions from the year before.

“There’s sort of a disconnect between our financing system and audience demand,” says Fitzgibbons. “Our financing system is currently based on the broadcast model, and audiences outside of the broadcast model are thirsting for documentary.”

This divide could be seen when waiting in the rush ticket line for Jennifer Baichwal’s newest work Watermark, also part of the Atlantic Film Festival.

At 10:15 p.m. on a Tuesday night, a lineup of dehydrated fans sat, or stood, outside the admission area, hoping they could still get a ticket to see Baichwal’s film on the big screen.

Known for expertly composed cinematography – by her husband and partner Nick de Pencier – this film is comprised of stunning aerial shots and an alluring essay concerning how we affect and are affected by water from all over the world. The production cost $1.7 million, and not a cent was financed through the traditional broadcaster model.

Their most expensive production yet is an anomaly, because it was financed mainly by private investors. In co-production with Edward Burtynsky, one of Canada’s best-known photographers, collectors of his work helped fund Watermark. This type of funding is one that traditional documentary filmmakers may consider in the future.

Though this method may have helped them make this film, the filmmakers themselves are still struggling financially.

You’re no longer just a filmmaker, you are now somebody who has to be a community builder.

– Velcrow Ripper, Canadian filmmaker

“It’s always an ‘Is there a cheque in the mail?’ sort of situation,” says Baichwal from her home in Toronto. “The reason we’re able to do these films is because Nick goes out and is sought after as a cinematographer on other projects. We can’t afford to live on what we make from the films that we do together.”

Regardless of the financial pressure, Baichwal will pursue her passion. “For me, documentary is a vocation,” she says. “I found the thing that I feel really engaged by.”

Engaging an audience and stimulating conversation is one of the ways documentary adds to Canadian democracy. John Grierson conceived the genre in the 1930s when asked to interpret Canada to Canadians and other nations. The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) was born, with Grierson in charge. Documentaries of that time were purely propagandistic, aimed at fighting fascism.

The NFB, a public film and media producer, is still financed by Parliament and still producing Canadian content. It’s also suffering from a few punches. In April 2012 the NFB had to eliminate 61 jobs when 10 per cent, $6.7 million, of its budget was cut.

“It makes it harder,” says Michelle van Beusekom, NFB assistant director general of the English program, from her office in Montreal. Job cuts for the NFB meant offices were closed across the country. Part of the board’s mandate is to tell stories that reflect all of Canada. “The more we’re cut, the harder it becomes to maintain that national structure.”

“We become a little bastion or bubble that is still really committed to documentary filmmaking, but we’re small,” says van Beusekom.

According to the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), it is the role of Canadian broadcasters to provide citizens with Canadian content in exchange for having access to the airwaves – an agreement Fitzgibbons currently abhors. “Broadcasters have stepped back from their obligations to provide a wide range of programming for their audiences,” she says.

It hasn’t always been this way.

“Five or six years ago,” says Walker, “you would go to Hot Docs and you would have four or five broadcasters asking you what are you going to do next; competing for your attention. That’s no longer the case,” says Walker.

With a little ingenuity and new communication methods, persistence, patience and passion can still pay off.

After 13 years of trying to finance her film Better Living Through Chemistry, Connie Littlefield of Halifax left for California in October 2013 to begin shooting with Passion Pictures.

“I’m probably the luckiest person in the world,” she says.

When private and public broadcasters weren’t working out, Littlefield decided to turn to people’s pockets, and started a crowdfunding campaign.

Using Kickstarter, the world’s largest crowdfunding platform, Littlefield started a fundraising campaign in 2010. The private, U.S., for-profit website enabled her to get in touch with the people who eventually ended up paying for the film.

Since its inception, Kickstarter has raised more than $100 million U.S. to support the creation of independent films. More than 100 of its funded films have been released in North America. It collects a five per cent fee for successful campaigns. If a campaign doesn’t meet its goal, neither party gets paid.

Velcrow Ripper is another Canadian filmmaker who has gone the creative route of crowdfunding. Real events taking place in Egypt, Spain and New York City could not wait to be captured. Born in B.C. and raised in the Baha’i faith, Ripper’s religious studies and films have taken him around the world. In the fall of 2013, he was in New York working on two productions.

“We had an idea, we wanted to proceed and we didn’t want to wait to get a yes from somebody, so we created our own yes by doing a crowdfunding campaign,” he says.

His film Occupy Love used Indiegogo, another crowdfunding platform, to be financed. Indiegogo allows users to keep the money they raise, regardless of whether they reach their goal. The website keeps four per cent of the proceeds from a successful campaign, and nine per cent from unsuccessful ones that don’t opt to return proceeds to contributors.

“It’s not like you hold out your hat and it fills up with money,” says Ripper. Indiegogo requires users to have social media pages to promote their fundraising efforts. Ripper ensures his Facebook page for Occupy Love stays alive by posting engaging messages for his project’s audience.

“You’re no longer just a filmmaker, you are now somebody who has to be a community builder,” he says.

This is how Mandy Leith sees herself. She believes the documentary industry might need community building to successfully move into the Internet age.

Leith is the creator of Open Cinema. Based in Vancouver, Open Cinema is a non-profit that screens thought-provoking films in café style venues in order to stimulate conversation.

She took a Volkswagen van across Canada in summer 2013 as part of an initiative called Get on the Doc Bus. Her aim was to help figure out a future for Canadian documentary filmmakers, and she was inspired to start a nationwide community cinema network. “Everywhere I went the vast majority of responses involved some understanding of the way in which community building is contributing to their success,” says Leith.

Walker’s Arctic Defenders shares this message. Community can be built in many ways. Inuit culture traditionally explores community through storytelling and songs; neither commodity can be bought or sold.

“Maybe we’re returning to a more tribal root of exchanging culture,” says Walker. “It’s a transition.”

In 1983 Walker was a founding member of DOC, then called the Canadian Independent Film Caucus. “That was the beginning of the realization that documentary was potentially threatened with a lack of funding,” he says. The newly organized group fought back, and convinced broadcasters to create a space for cultural content that could inspire conversation. They won.

“Young Inuit in their twenties wanted to make a change, they wanted to protect their language and culture and maintain control and governance of their territory: Nunavut. They were able to pull off the largest land claim in the history of Western civilization,” says Walker. “They started off with a handful of individuals with a vision… that’s the message (of Arctic Defenders). We have to believe in ourselves, stick together, and have a vision.”