Who is caring for mental health workers?

Politicized practice might help relieve worker burnout

Despite juggling seven jobs and running three businesses, Abby Chow doesn’t generally feel the need to decompress from work. Chow, the founder and clinical director of Venturous Counselling & Consulting, is a registered clinical counsellor based in what is colonially known as Vancouver, BC.

When not supervising counsellors-in-training at Adler University and Vancouver Community College, she’s providing businesses with justice-oriented consulting services. And those are just a few of the many hats she wears.

There are moments when Chow lists out her jobs and asks herself: “Wow. Do I even have time to sleep?” Decidedly, her answer is yes. “I’m actually living quite well,” she says. “I’m lucky enough to have my profession be very personal.”

The personal is political

Chow has been a practicing therapist for more than a decade, but the business major-turned-counsellor wasn’t always set on pursuing mental healthcare as a profession.

Originally from Hong Kong, she immigrated to so-called Canada as a teenager. Growing up working class with parents that didn’t speak English, much of her insight into how systems of oppression can affect people’s mental well-being stems from firsthand experience.

It’s not lost on her that systemic violence can seep into and be perpetuated by counselling relationships. “I always have to think: in what way is my work actually benefitting the structures of colonization and capitalism?,” she says.

Chow believes there’s a professional standard that therapists should always be politically neutral. But she thinks that does a great disservice to both clients and therapists, especially those belonging to marginalized communities.

“Our role is to not exist in the counselling room, because our clients must take up all the space,” she says. “But I don’t think that’s possible. I’m also human. I also have (social) locations. And with the work we do, connectivity is required.”

The standardization of client-centered practice can be traced back to the 1940s work of U.S. psychologist Carl Rogers. In his book Psychology: A study of a science, Rogers argues that this practice requires therapists to communicate empathy and unconditional positive regard for their clients. It’s an approach that’s long been endorsed by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, which first made its belief clear with its publication of Guidelines for Client-Centered Practice in 1983.

A 2022 study published in The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, while honouring the merits of this practice, notes that it potentially minimizes situations in which marginalized therapists can be the subjects of systemic violence, too.

While national demographics about mental health practitioners remain few and far between, 2016 census data shows that “visible minority” therapists make up about 14 per cent of occupational therapists. Out of this number, it’s unclear what proportions identify as Indigenous, disabled, queer, of working-class origin and/or an ethnic minority. Data about discrimination faced by marginalized therapists in the country is also scant.

“I don’t think we get much care,” says Chow. “We very much exist in the binary of you get cared for, or you are caring. And that’s something that’s set up by the institutions, I think. We’re left to just be in those spaces. To care for ourselves.”

Self-care for carers

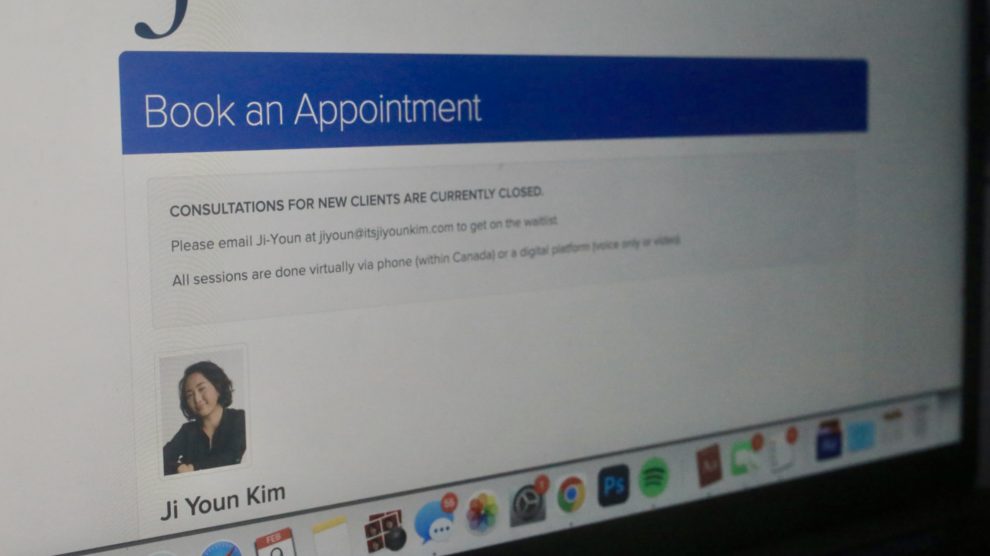

Ji-Youn Kim, a registered therapeutic counsellor with the Association of Cooperative Counselling Therapists of Canada (ACCT), also works out of so-called Vancouver. Kim identifies as a non-disabled, middle-class, cis, queer-adjacent woman and settler of Korean ancestry. (Disclosure: we have had a counselling relationship for two years.) Self-care for counsellors is encouraged by associations such as her own, she says.

In order to maintain her registration with ACCT, Kim has to hand in an annual competency report logging a certain number of hours for client work, clinical supervision, professional development and self-care.

What qualifies as self-care, however, is open-ended and generic, says Kim. These requirements can be fulfilled by receiving personal counselling, attending mental health-focused workshops, or by engaging in “other self-care practices,” according to ACCT’s website.

Similarly, members of the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association, a national association of professionally-trained counsellors, are expected to familiarize themselves with the association’s code of ethics and standards of practice. Both documents frame self-care for counsellors as a “professional responsibility” to maintain optimum capacity in their line of work, but neither document defines what self-care entails.

“All of it’s dependent on an individualized, de-politicized perspective on self-care,” says Kim, who believes that a lack of self-care guidelines sweeps the needs of marginalized therapists under the rug. “I wouldn’t say that there is any institution- or larger organization-based support.”

Chow, who is a member of the BC Association of Clinical Counsellors, points out that resources available for registered counsellors mainly take the form of professional development opportunities rather than tangible emotional supports. The BC Association started offering a peer network for counsellors, she says, but that only got put in motion this year.

“The professional development stuff is a little bit too colonial for my tastes,” Chow says. “So I don’t really participate in that.”

Systemic violence leads to therapist burnout

A 2020 crowdsourcing initiative by Statistics Canada reveals that the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified reported rates of discrimination against visible minorities.

Vincent Mousseau is a registered social worker based in so-called Halifax, NS. They’re also a founding member of Lambda Health, a non-profit workers’ cooperative of 2SLGBTQ+ clinicians specializing in online counselling and speech-language pathology services for queer communities.

Mousseau’s initial response was to refer these people to other mental health providers. But when fluency in systemic oppression often requires embodied experience, and there are few people qualified to provide mental health services catering to the Black queer trans experience, Mousseau says it is hard to just not see these clients who are knocking at their door for help.

That said, Mousseau also has to balance work with being a doctoral student. Their current research studies the barriers that Black men and masculine-of-centre non-binary people face in accessing health and social services. And Mousseau can only accept so many clients, as their Vanier Scholarship limits the hours they can work as a social worker per week.

“To have to turn people away for that is really sad,” they admit. It took a long time for Mousseau not to internalize the narrative that they were a bad social worker for not helping community members in need. Working on research to better their communities, on top of offering mental health services as a social worker, they say, counters feelings of helplessness that can sometimes arise.

caption

Kim’s client waitlist has been closed for months. Her workdays generally consist of four back-to-back, 50-minute sessions with clients. Every once in a while she’ll take on five sessions in one day, but she’ll often feel herself start to wane by the end.Still, these feelings aren’t as uncommon as one might think. Kim and Chow both understand how the individualization of systemic oppression can contribute to worker burnout in the mental health professions.

So many mental health challenges trickle down from systemic trauma and basic unmet needs, Kim says. Instead of addressing affordable housing, the opioid drug policy crisis, and dismantling other systems of oppression, she says, the capitalist state continually sends people over to mental health providers for treatment for societal symptoms that are unaddressed on a systemic level.

“I used to really dismiss my work because I was like, ‘Oh, therapy doesn’t solve anything. It’s not the solution’.” Then she twitches a grin as if finding what she said terribly amusing. It’s because her approach has changed since.

“Therapy can be a really helpful way to recognize the areas and spaces of agency while we live under these oppressive structures,” Kim says. Dismissing therapy in its entirety does both carer and cared a disservice: it denies people’s agencies and capabilities to enact structural change within and beyond the therapeutic relationship.

A lot of times folks can understand the context of systemic oppression, but they’re looking at it from the lens of “What can you personally do about it?,” says Chow. “Sometimes you’re just sitting in a room and you’re like: ‘Yeah, us alone is powerless here’.”

In her view, much of the therapist profession as it stands deals with how to cope with the livability of life. “Part of me questions how much coping is actually just maintaining the status quo. How much am I supporting you to cope with unlivable conditions instead of allowing that experience of it to motivate us toward change?”

The unique positioning of therapists drives Chow to leverage her role to change what is considered societal norms, both in and out of the counselling room. “Through our conversations, where literally what we do is just sit there and chat, we’re creating new stories and new ways of seeing the world,” she says.

“We can use our profession to move the needle for the next generation. I think that’s what keeps me alive in this work.”

Grassroots solutions to caring for therapists

On top of all the jobs Chow works, she also oversees Reflecting on Justice, a virtual platform she runs for therapists looking to unlearn systemic oppression within themselves and their profession. The site hosts anti-oppressive reflection questions for practitioners, a signup sheet for Chow’s newsletter where she shares her learning, and a $36 crash course on justice-oriented practices.

In line with Chow’s commitment to dismantling structural inequities, half of the proceeds on the platform are redistributed to Indigenous organizing efforts, independent anti-oppression educators, and marginalized individuals in need of finances.

Chow says she got lucky during her school days. That’s when she met Vikki Reynolds, an influential professor who took her under her wing. Reynolds generously included her in the justice-oriented communities that she had built. For Chow, this access to like-minded practitioners was incredibly enriching.

Learning that other therapists didn’t have access to the peer networks she did was a shock. “How did you even survive that long? How are you still in this work? You don’t have people around you!” Chow says. Discovering how isolated other practitioners felt in politicizing their work motivated Chow to create this resource for her peers. Continued interest expressed by her counselling students at Adler, who only get 12-14 weeks to unpack systemic oppression in class, also led to the creation of Reflecting on Justice.

It’s Chow’s way of mitigating the systemic harm that mental health professionals can subconsciously perpetuate and be affected by in equal measure.

Ultimately, Chow pays homage to grassroots activists Adrienne Maree Brown, Sonya Renee Taylor, and Mia Mingus, who use the term “collective liberation” to describe how the liberation of all people from oppressive systems is tightly bound together.

Chow ends her interview by recalling a crucial idea by community organizer María Poblet: “Burnout is not about the amount of hours worked, but the amount of political clarity you have,” she quotes.

And so when Chow says she’s lucky to have her profession be personal, she’s not lying. Renegotiating therapists’ role in care work is her way of caring for both others and herself.

About the author

Audrey Chan

Audrey (they/them) is a journalism student at the University of King's College. They have a background in Contemporary Studies and Cinema &...