Why big supermarkets aren’t jumping on the zero-waste train

Safety and profit concerns might deter stores from going package-free, food expert says

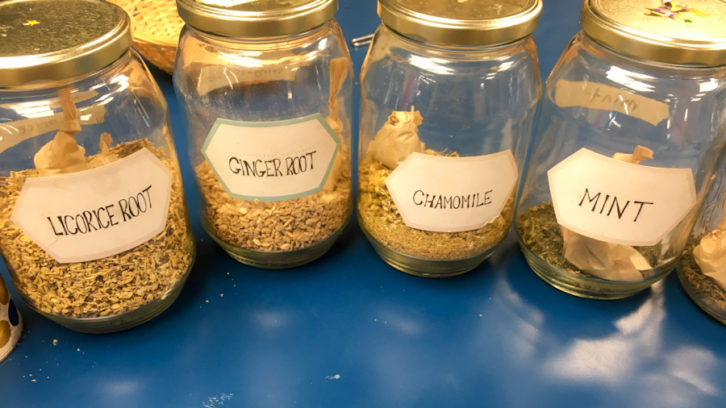

caption

Jars of dried goods at the Tare Shop on Cornwallis Street, Halifax N.SWith the zero-waste movement gaining traction in Nova Scotia and Sobeys giving plastic bags the boot by Jan. 31, one expert has ideas about why grocery stores aren’t so quick to hop on the bandwagon.

Sylvain Charlebois, Dalhousie University professor and food distribution researcher, wrote in an article that 40 per cent of what people put in their grocery carts results in food waste. Additionally, the equivalent of 24 CN Towers, or 2.8 million tonnes of plastic, end up in Canadian landfills every year.

While Nova Scotia recently passed legislation to ban single-use plastic bags later this year, stores are still selling much of their produce wrapped in plastic.

caption

Pre-packaged watermelonIncreased concerns around climate change means more Canadians are thinking about better ways to shop and smarter ways to store their food.

The concept of zero-waste shopping means everything is sold in bulk without packaging. Products are weighed and priced and shoppers bring their own containers to carry their food home.

In 2007, the first zero-waste market called Unpackaged opened its doors in London, U.K. Today, similar stores can be found in many countries.

Markets like Ecoindian in Tamil, Alang-Alang in Indonesia, Rifuzl in Slovenia, Ripple Living in London all feature zero-waste shopping. The Tare Shop in Halifax is also part of this increasing trend.

caption

The front of The Tare ShopCharlebois said food safety concerns and profits are possible reasons why grocery stores may be reluctant to adopt zero-waste shopping.

“Generally speaking they (supermarket chains) are concerned about food safety,” he said. “Secondly, if you don’t do any assorting, you are less likely to make money.”

Assorting is a retail strategy which involves organizing specific products in a way that optimizes sales. For example, you might want to buy one onion, but the only option provided by the store is to buy a bag of several onions.

“Assorting is not necessarily allowing the consumer to customize the amount that they want,” he said. “By doing so, you do actually generate more sales, and to get away from that is dangerous from a financial perspective for grocers.”

Looking ahead, Charlebois thinks compostable packaging or biodegradable packaging is the future for big chain supermarkets.

“If you don’t disrupt the flow of someone’s life, you have a better chance of success,” he added.

Kate Pepler, owner of the Tare Shop on Cornwallis Street in Halifax, has a different perspective.

She believes big chain supermarkets have the ability to do away with packaging. She points to several supermarkets in the U.K. that have converted to zero waste. She disagrees with biodegradable or compostable plastic being the solution.

“Most biodegradable or compostable plastics are not recyclable in HRM. I urge people to avoid them,” said Pepler.

caption

Chicken wraps packaged in plastic wrapIn an interview, Eli Browne, director of corporate sustainability for Sobeys, said the company doesn’t rule out zero waste being a feasible business model in the future. But she said the company has concerns about how the practice may be received by customers.

“We’ve tried it in one of our banners (stores) with bulk spices and it just didn’t work out. There was a lack of trust, like whose fingers have been in that bulk spice,” Browne said.

“In other banners, the bulk section does very well because that consumer base is kind of used to the practices. So it can vary from store-to-store, but generally speaking, we do want to make it easier for consumers to reuse.”

caption

One way to reuse jarsBrowne said Sobeys has several key priorities. Reducing food waste and single-use plastic are at the top of their list.

“Waste reduction is really how we focus our approach. Where can we prevent, eliminate, minimize, reduce that waste in the first place,” said Browne.

Browne also pointed out that Sobeys has a food donation program. In 2017 they partnered with Feed Nova Scotia. They now donate fresh produce, meat and beauty products nearing the end of their shelf life.

“There are so many details, big and small, to think through when you’re making a change across a large organization,” she said.

“We want to be strategic but pragmatic, which is why we’re taking our elimination of plastic bags banner by banner, brand by brand. Same type of an approach with the ‘bring your own containers.’”

In September 2019, the company piloted a “bring your own container” program in its IGA grocery stores in Quebec.

“Now that it’s been running for a few months we’re now comfortable to expand it outside of Quebec,” she said.

There are no immediate plans to introduce a Sobeys “bring your own container” program to Halifax, but Browne said the company has a detailed sustainability report coming out this summer about Sobeys and its environmental initiatives.

Charlebois said when it comes to zero-waste shopping in Canada, the market isn’t quite there yet.

“We don’t see it in the numbers but it doesn’t mean we’re not going to get there eventually,” he said. “But for the masses, there is a long way to go.”

About the author

Feleshia Chandler

Feleshia is a freelance journalist who has contributed to the Coast and Quench Magazine. She enjoys writing about feminist issues, LGBTQ issues...