Writing the next chapter

caption

Some writers have adapted their storytelling during COVID-19 to rely less on in-person scene setting.Cancelled book launches and financial hits. How Nova Scotia writers are faring as COVID rewrites the script

Nonfiction writers in Nova Scotia work from home during the pandemic, as many did before, but now have to work with cancelled book-launches, financial uncertainty, and a new environment.

“It took me a while to find my footing for my own writing,” says Lorri Neilsen Glenn, Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia president. “The combination of the pandemic and the volatile political situation in the United States was endlessly distracting despite my efforts to tune it out.”

Glenn started a pandemic newsletter for Atlantic Canadian writers, allowing them to reflect on their experiences.

“A lot of human suffering made even more visible is humbling and heart-breaking, and the myriad ways people have experienced and written about the pandemic helps us connect,” Glenn says. “We learn we aren’t alone.”

Writers helping writers

The writers’ federation is a non-profit organization that offers a variety of professional services to support the craft of writing and the promotion of local culture and the economy through Nova Scotian writers.

Marilyn Smulders, WFNS executive director, says the Second-Wave Relief Fund was developed to help writers who may have part-time employment, or book releases or publications delayed because of COVID restrictions.

The fund provides one-time payments of $250 for authors in need. The funds are raised through a subsidy program where members donate and the federation matches donations. To date, $3,000 has been donated, Smulders says. The fund will continue until all the money has been disbursed or until the end of the WFNS fiscal year, March 31.

Reading, writing and income during a pandemic

BookNet Canada surveyed 748 Canadians from Mar. 30 to April 9, 2020, to analyze reading during the pandemic. Fifty-eight per cent of readers surveyed say they are reading more, 39 per cent have maintained their reading, and 4 per cent are reading less. The majority were getting their books online, but some would still get them from a bookstore with in-store or curbside pickup/delivery, and many also used the extra time during pandemic lockdowns to read books they already owned.

According to BookNet Canada Sales Data, nonfiction had 40 backlisted (books published before January 1, 2020 and still in print) books enter or re-enter the top 100 in sales since the pandemic began.

Alex Liot, chief marketing officer of the Atlantic Publishers’ Marketing Association, says the local publishing industry is back on track, after an initial drop in sales and an exceptional summer of reading and active engagement with the community through the #ReadAtlantic Campaign. Exact numbers are difficult to gather, due to unreported sales from smaller publishers, but BookNet Canada collects sales data that shows sales volume and sales value for members, Liot says.

According to a report shared with him, Atlantic book sales initially were down around 40 per cent, but sales were up 18 per cent in the summer period over the previous year, and after a very successful holiday season, ended the year with the same total sales as in 2019.

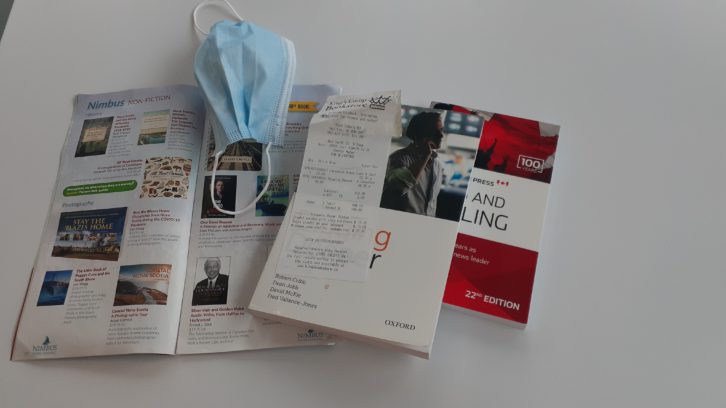

caption

Atlantic book sales were down during the initial lockdown, but recovered over the summer and holiday season.Some publishers were affected by COVID more than others, Liot says, including Pedlar Press in Newfoundland, which shut down. Similarly, potential book sales were lost in a lot of tourism venues and gift shops that would normally have been open.

Some of the early challenges of the pandemic included printing, Liot says, and interprovincial and international trade in books, due to border restrictions, and promoting new books without launches due to social distancing. However, Liot also remarks that many authors work from home and have used some of the lockdown to work on their craft.

Chasing stories during a pandemic

Working from home is familiar to Philip Moscovitch, who lives in Glen Margaret with his wife, Sara Lamb, surrounded by woods. Fresh air and the crunch of ice underfoot have remained a part of his routine during the pandemic, when for some other people, it has been much harder to get outside safely.

His craft is writing; and his tools are a laptop closed on a desk and connected to a large monitor, with a Bluetooth mouse, and a full-sized keyboard. Sometimes, Moscovitch says, he’s been writing on his couch for a change of pace.

Philip Moscovitch writes nonfiction – he’s a regular contributor to magazines including Saltscapes, Halifax Magazine and others – fiction, produces audio documentaries, and provides writing and editing services. He completed an MFA in Creative Nonfiction at University of King’s College in 2019.

Early in the pandemic, I was really worried about my livelihood, all these publications depend on local advertising and the businesses were closed. Paul Moscovitch

Halifax Magazine went on publishing hiatus in April, 2020. During March, April, and May, Moscovitch says he worked a lot, due to uncertainty of future income and whether publications would stay open.

During COVID, Moscovitch says his writing has changed to focus on shorter journalism pieces that are easier to do from home, compared to creative nonfiction stories that require scene-setting and often involve shadowing people in person.

“If you think back a year ago, there were all these questions,” Moscovitch says, “I kept thinking of story after story, like okay, what’s affected by this, and how does it change?”

Last June, Moscovitch explored one of the pressing questions: what does a COVID test involve? His article was published in the Halifax Examiner, detailing his experience as he questioned his possible symptoms, called the Nova Scotia Health Authority and got a test.

COVID testing has become a common experience; the discomfort of sitting as still as the chair underneath us, tilting our head back, and the intense pain in our nose. Relief from the physical pain followed by anxiety; self-isolation until the call. Moscovitch says at the time, he didn’t know anyone else who had a COVID test so he wrote about it, but now it wouldn’t make any sense. Almost 400,000 tests have been completed as of March 19.

“Maybe what I’m working on has changed, but not how I’m living my life,” Moscovitch says. While experiencing severe anxiety in the beginning of the pandemic, he has mostly returned to his daily life in Glen Margaret.

Daniel Paul is a business manager, consultant, counsellor, author, journalist and reviewer, best known for his book, First Nations History: We Were Not the Savages (published first in 1993, reprinted in 2000, with a third edition in 2006), about the history of ancient democratic North American First Nations, from a Mi’kmaq perspective, and the near demise caused by the European invasion of the Americas. “When you’re looking at Nova Scotia, white man’s history was written, with a very slanted view towards making the white man a hero,” says Paul, a Mi’kmaq elder who lives in Halifax.

Paul says he writes occasional pieces for Mi’kmaq-Maliseet Nations News and occasional letters to the editor. Because of COVID, he had to stop giving lectures at universities, and hasn’t done any in over a year, but may resume them in the fall after vaccinations, if it is safe at that time.

Book launches and social distancing

Ernest Dick is an archivist writer in Granville Ferry who focuses on oral history.

“I believe stories, rather than genealogy or DNA, tell us who we are,” Dick says. “So I’ve been interviewing people to pursue their stories forever, and over the years I’ve created a number of books from those interviews, so that, you know, is a continuing process.”

caption

Many writers worked from home before the pandemic.Granville Ferry is a small seaside village with little traffic, and he walks to town, without needing the loud engine of a car to carry him. He says this helps him get daily physical exercise. Sometimes, he may walk over the mountain towards the Bay of Fundy shore, he may cross-country ski or ride his bicycle. Balance is important, and he says he does this as much as writing.

In the beginning of the pandemic, a lot of events were cancelled, postponed, or shifted online to accommodate social distancing, including book launches.

Two of Dick’s books, Silver Hair and Golden Voice: Austin Willis, from Halifax to Hollywood and Pursuing Clara, were published in late 2020.

Halifax’s Nimbus Publishing hosted a launch for Silver Hair and Golden Voice in Halifax, one of the last public events it staged, Dick said, and the turnout was poor.

If it weren’t for COVID, it would have been a great, great afternoon of recollections. Ernest Dick

A similar experience occurred with a local bookstore that had planned a launch for Pursuing Clara.

“There’s no doubt that COVID impacted both of those books being launched,” Dick said, “because people are not comfortable coming out to be together.”

It was a full night of celebration on June 4, 2014, at the Stevens Road United Baptist Church, in Dartmouth. Over 200 people filled the space for the launch of The Winds of Change: The Life and Legacy of Calvin W. Ruck, written by Lindsay Ruck, author and editor who lives in Dartmouth.

“It was really nice to see so many people show up for him,” Ruck said. “I know they weren’t there for me, they were there to celebrate his life, which was really nice because that’s what the book is, celebrating his life.”

The subject of The Winds of Change is Lindsay Ruck’s grandfather, who was also an author of a nonfiction book, The Black Battalion 1916-1920: Canada’s Best Kept Military Secret. His passion to share stories and advance Black Nova Scotians and Black Atlantic Canadians, she says, was a huge inspiration to her and a part of what she does now.

Writing biographies is an important responsibility, Ruck says. “People are trusting you to tell the story of their life, which is huge.”

Because of COVID, she hasn’t been able to have similar launches for her new work.

Lindsay Ruck writes with the flow of ink to paper; methodically putting her thoughts down before turning to word processing. She is also a wife and mother of a three-year-old daughter and a younger son, who was born the day before lockdown measures began in 2020.

She is accustomed to motherhood and the demands of writing. “When you’re a freelancer, there’s really no such thing as maternity leave,” Ruck said, but this time is different because of the pandemic.

Her daughter would be spending time in daycare, and friends and family would often visit their house, providing much-needed support for new parents. During COVID and the birth of their second child, Ruck and her husband have been busy. Her husband holds their son while she thoughtfully speaks through the metallic speaker of a smartphone.

That was a huge adjustment for me, just to kind of figure out how I’m going to get this done with two little ones at home – one who doesn’t know why she’s not in daycare anymore, and another one who’s brand new to the world.Lindsay Ruck

Her most recent work is an illustrated book for kids, Amazing Black Atlantic Canadians, which features 50 Black people from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador, past and present. The pandemic affected the publishing date, Ruck says, and it came out on Jan. 26, later than originally planned.

She dedicated the book to her children.

“I want them to have a book that I didn’t have when I was growing up,” Ruck says, “which is a book that celebrates these different Black men and women so they can see them and be inspired by them.”

Writing, self-expression and coping

Marjorie Simmins, journalist, author of memoirs, magazine articles, teacher and more, speaks easily on the phone about her passion: writing. Her desk is full, her writing process is methodical, and she describes her practice of editing as she goes.

“Impacted?” she’s asked, and she interjects with an analysis of vocabulary. “It’s something that hits you,” Simmins explains how strong the verb is. “Affected,” she’s asked, “That’s better,” she agrees.

I cannot imagine my life at any point, COVID or otherwise, without writing. Marjorie Simmins

As a child, boredom was addressed with paper and instructions; “write your grandmother.” She came from a family of writers and letter-writing, and this was her first introduction to what would start her career. Simmins recalls the magic of sending a letter in the mail and receiving one back, “Somebody loves you, somebody cares enough to sit down and share their thoughts and feelings with you.”

caption

Marjorie Simmins says she still writes three letters a week.She says writing is who she is, and how she processes the world. “It’s how I give to other people, it’s how I share humour …. I don’t know how I feel until I sit down and write about it.”

Her first memoir, Coastal Lives, was published in 2014, about leaving the West Coast and meeting her husband, Nova Scotia author Silver Donald Cameron, and deciding to have a life with him in the Maritimes.

She describes writing as a lonely business, working alone in a house, questioning if work matters, drafting on end, but this isolation is buffered by the writing community in the Maritimes. Simmins says she finds the Atlantic Canadian community to be supportive, kind, smart, brilliant, and aware of what others are doing – on Facebook, Twitter, and other mediums.

During COVID, Simmins’ husband died and she has not been able to have family visitations to help her through this difficult time because of social distancing.

While she enjoys jokes and humour in her writing, Simmins said her writing is more somber than usual. “None of us are feeling too ‘ha-ha,’ right now.”

“I’m way too disciplined after all these years to completely drop the thread of writing at any point, you know,” Simmins said, “When I lost Don, I grabbed onto that thread for all I was worth.”

Simmins says she will be happy when we can return to hugs, kisses, and closeness with other people.

About the author

Chelsy Mahar

A journalism student at the University of King's College and an aspiring poet.