Zooming in on therapy

caption

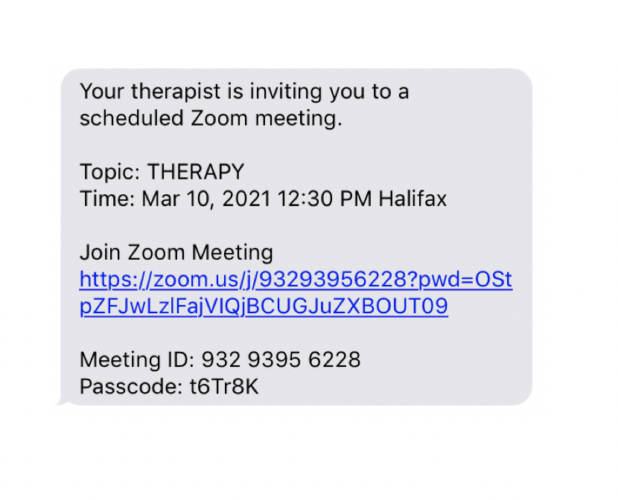

Many clients and therapists have resorted to Zoom therapy, so they can continue with their sessions through the pandemic.Future of psychotherapy could be a 'hybrid' of in-person and virtual sessions

In March 2020, Dr. Nina Woulff considered herself “a total online virtual therapy virgin.” Now, she’s a pro.

Last year, the world shut down due to the pandemic. Overnight, people were told to stay inside and stop socializing. And when many people, isolated and alienated from their support systems, needed therapy most, they – and their therapists – had to swiftly adjust.

In Canada, statistics from the Angus Reid Institute show that one out of two Canadians are reporting that their mental health has deteriorated since the pandemic began. According to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, the percentage of American adults who are suffering from symptoms of depression and anxiety rose from one in ten experiencing symptoms in 2019 to four in ten during the pandemic.

There are practitioners who have been doing online or telephone virtual therapy for years. But therapists who had never done virtual therapy were scrambling to get something set up as the pandemic began.

Many wondered how helpful they could be, without the physical presence of their clients and with the added barrier of a computer screen.

A scary transition

Woulff, who has a PhD in psychology, knew little about virtual therapy at the beginning of the pandemic. A practicing psychologist in Nova Scotia since 1974, she opened her practice, Nina Woulff and Associates, in 1994.

Pre-pandemic, Woulff says that she and her colleagues engaged in a “very, very, very limited amount of phone therapy.” She says such consultations were done when there was bad weather or when university students went home for Christmas and wanted to continue with their sessions.

“People were reluctant to even try it. Now, it’s like part of our language.”Nina Woulff

Because of the location of her practice, at Spring Garden Road and Robie Street, near the Dalhousie campus, Woulff sees a lot of university students. She knows the strain that online teaching is putting on students, because Woulff is a student herself, completing a Bachelor of Music degree part-time.

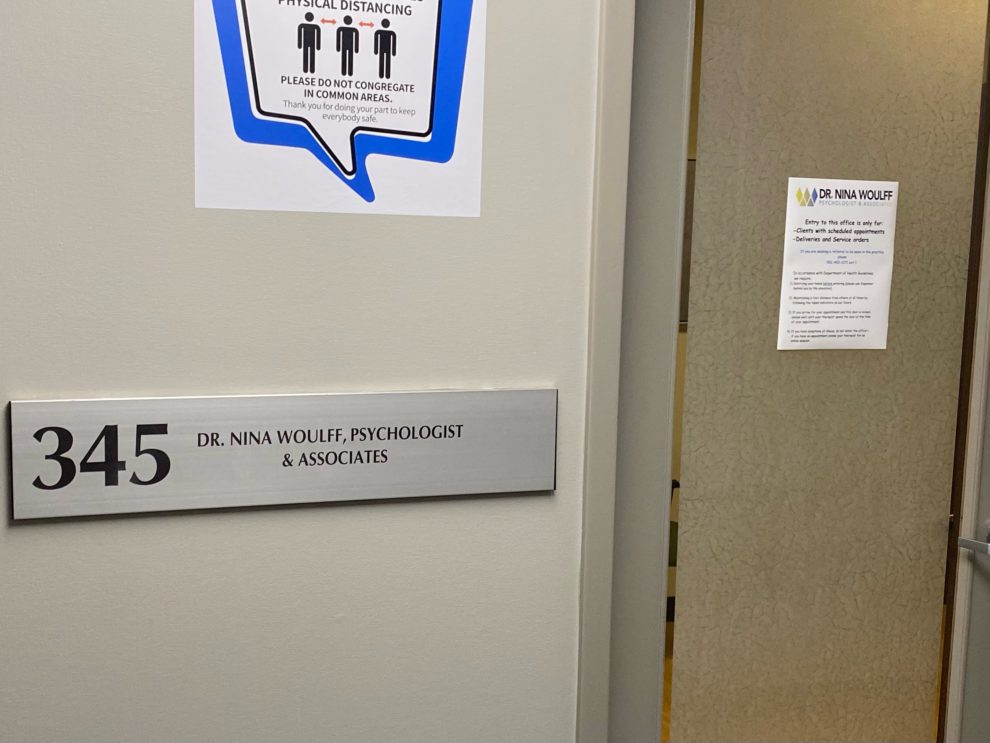

caption

Nina Woulff and Associates’ offices in Halifax. She has begun to see clients in-person, but continues to see some virtually.At the beginning of the pandemic, many of Woulff’s clients were apprehensive to start online therapy, as she was. They weren’t sure how something as personal as therapy could be mediated by a screen.

“People were reluctant to even try it,” Woulff said. “Now, it’s like part of our language.”

Maxime McLean, a 24-year-old student at the University of Calgary, knows how scary starting therapy online can be. She was in therapy pre-pandemic, to help her cope with her dad’s illness.

Having never thought about therapy, she was pleasantly surprised at how cathartic it was to talk to someone about her feelings, and how quickly she was able to open up.

“After talking to her for the first couple times, it was very eye-opening and clarifying for me. It was really nice to have an unbiased person that’s just like solely there for you and wanting to support you through this,” said McLean.

When the pandemic hit, McLean had to switch to online therapy, which she says was seamless because she had a good rapport with her therapist. When her father died in the summer of 2020, she couldn’t see her current therapist anymore. She wanted to find a new one to speak with, especially during this time. She’d be meeting them for the first time online.

“It was kind of nerve-wracking because it’s kind of awkward to see someone for the first time and open up about all these things.” McLean laughs, saying she had to explain her “entire life story over Zoom.”

Something that McLean’s therapist said stuck with her. “She said to me, ‘you develop a connection with your therapist in the first two minutes of their conversation.’ So, you either get a good vibe or bad vibe right away.”

And McLean did get a good vibe. “She did a really good job of just listening and ensuring that I felt comfortable in the first five minutes.”

Coming to terms

Dr. Gillian Isaacs Russell was ahead of the curve. In 2015 she published the book Screen Relations: The Limits of Computer-Mediated Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. Virtual therapy was something a lot of people were still wary of, thinking it might be impossible to replicate the “space” that therapy holds for the client and therapist.

Isaacs Russell got her start in online therapy after moving from the United Kingdom to South Dakota. She ended up in the Black Hills, home to Mount Rushmore, and the idea of online therapy to keep connections to her patients in the UK was “extremely appealing.”

“Is this something that we can do? Is it functionally equivalent to be working online, rather than embodied in a room together?” she recalls asking herself.

Little did she know when she published the book that within five years, just about everything would be online.

“A complete lockdown, where there was no choice and no preparation. Virtually overnight,” Isaacs Russell says. “We had to come to working in a mediated way with technology in order to continue what we were doing.”

This abrupt change uprooted what was sacred for clients. Their experiences in therapy up to this point had been consistent and predictable.

caption

According to therapists, during online therapy both clients and therapists can miss out on non-verbal cues that help them communicate more effectively.

But is online therapy viable?

According to a 2014 study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, “internet-based intervention for depression is equally beneficial to regular face-to-face therapy.” A more recent study, published in 2018, found that “computer therapy” for anxiety and depressive disorders is “effective, acceptable and practical health care.”

Creating a secure space

Isaacs Russell, after writing her book and working with psychologists during the pandemic, is an expert in online therapy. While she believes online therapy can be beneficial for clients, she lays out a number of issues that can arise. The most important is that the therapist and the client are in completely different environments.

“Traditionally, the clinician provides a safe holding environment for the patient, so that the patient can have a sense of privacy, and safety and confidentiality in which to tell their story and to do their work.”

When you’re working from two different places, she explains, there are a multitude of things that can intrude.

McLean understands this. She now lives at home in Calgary, where she felt less secure speaking and opening up, partly because she didn’t want others overhearing.

“I’ve tried to coordinate with people I live with to make sure that they’re not there,” said McLean. “Or at least they’re in their rooms with headphones in …. I’m not really talking about anyone else but myself, but it still is personal.”

Lindsay Dupuis, an online counselling therapist who works with people all over the country, believes the ability to be at home can be a benefit.

For some, says Dupuis, “there’s a greater comfort in some ways, because people are at home. They don’t have to walk into a strange clinic where people may see them.”

While Isaacs Russell is adamant that you can make progress through online therapy, she concedes there are aspects that cannot be replicated virtually.

In person, there are non-verbal messages therapists can pick up “because we’re sensitive, and because we’re empathic.” On-screen, “many, many subtleties are lost.”

“Not only were there some people asking for office visits, they were actually begging. It was quite remarkable.”Nina Woulff

Isaacs Russell identifies another problem. “The movement both to and from a session for the clinician, as well as for the patient, is very important. It has a relation in our brain to memory, to laying down a memory of an experience.”

Despite this, Isaacs Russell says there are ways of making a transition even if you’re doing therapy virtually.

“We do suggest that if you can, you don’t go straight from one Zoom meeting to another … but you spend some time moving, whether it’s just walking around the block or walking around your flat.”

Moving forward

The hardest part of virtual therapy, Woulff says, was getting people to start online. Nova Scotia started to open up throughout the summer, and to her surprise, many of her clients wanted to stay online.

“Nova Scotians really have been very, very careful and cautious,” said Woulff. She thinks people wanted to stay online to ensure they weren’t exposed to the virus. Then, starting in September, not only did the Woulff’s referrals increase, her clients were desperate for in-person sessions.

“Not only were there some people asking for office visits, they were actually begging. It was quite remarkable,” she said.

The drastic increase in referrals in the fall is something that Woulff attributes to the cumulative effect of more than six months of pandemic life. She worries especially for the younger population.

“It’s alienating,” Woulff says about social distancing and public health restrictions.

Statistics from the American Psychological Association show that since the pandemic began, 74 per cent of psychologists who treat anxiety disorders saw an increase in demand for treatment. Of those providing treatment for depressive disorders, 60 per cent saw increased demand.

Despite her worries about the long-term effects of pandemic life, she believes online therapy can work.

“Can you get effective therapy? Online? Absolutely. It’s just people I think will be hungry, hungrier than they ever realized, for this kind of contact,” she said about the experience of being in a room with someone.

Despite this, Woulff is confident that “online therapy is here to stay.” But she predicts it will be more of an adjunct than mainstream.

Her office now offers the option of in-person or virtual sessions, and clients can change to a virtual appointment up to a few hours before a scheduled appointment. Woulff predicts this kind of flexibility is here to stay.

McLean says she’ll probably opt for the hybrid approach after the pandemic. The online option is convenient for times when she’s busy, but she is looking forward to meeting her therapist in person and continuing their relationship.

Isaacs Russell also predicts that a hybrid model of in-person and online therapy may be introduced to a lot of practices. Virtual therapy can be effective, she says, but not forever.

“I think that you can make some progress. But I think that to complete the therapeutic journey, you must at some point be in person.”

About the author

Natalie MacMillan

Natalie MacMillan is from Toronto, Ontario, and works out of Halifax.