COMMUNITY

Alone but not forgotten

caption

There are about five city-run common ground cemeteries in Halifax that buries unclaimed bodies.'Equally important as coming into this world, is going out of this world'

Rev. John den Hollander remembers the green garbage bag.

“All that he owned fit in a green garbage bag,” den Hollander says. “I felt bad simply because I thought, you fight when you come into the world to be born and he even had to struggle when it came time to die.”

It belonged to a homeless man who died on the street 15 years ago.

Den Hollander had met the man at the Salvation Army shelter, but he didn’t know him well. Nevertheless, he agreed to officiate the funeral.

“It was a memorial service because his body was still on ice, waiting to have an autopsy,” he says. “I remember I called and said, ‘if this were anyone else who had a family waiting for them, it wouldn’t have taken this long.'”

After the autopsy was preformed, the man was cremated.

This would be the first time den Hollander would officiate the funeral of a homeless person. Sometimes he is one of the last people to speak for a deceased person who could be his acquaintance, like the man who owned the garbage bag, or a complete stranger.

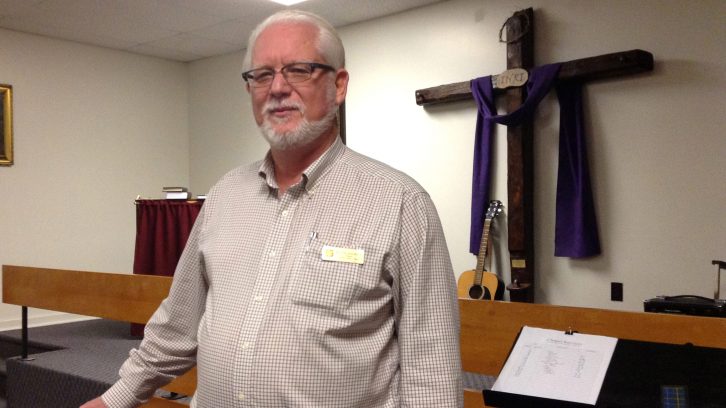

caption

Rev. John den Hollander, community chaplain at the Salvation Army.“You wouldn’t want to be that person that no one came to your funeral,” Dwayne Isenor.

Every year, there are people in Nova Scotia who die alone and sometimes there is no one to claim the body or organize their funeral. Some of them live on the street and have no home. The province covers funeral costs if there is no one to claim the body or if family members can’t afford a funeral.

Heather Fairbairn, spokesperson for the Nova Scotia Department of Community Services (DCS), explained via email that the process starts immediately after a death. First, police attempt to notify the next of kin, then the Medical Examiner’s office contact the DCS if they believe there is no one to claim the body. This is typically determined within a few hours or days.

The DCS then decides whether the deceased is eligible for funeral coverage. The maximum amount provided is $3,800 plus taxes. Of that, $2,700 is allocated for professional services such as cremation, embalming and an urn or casket, while $1,100 is for other items such as clothing, a grave lot, a reception, or cemetery charges. If there is a surviving spouse, they must demonstrate that they have exhausted all available resources for full or partial coverage of funeral services.

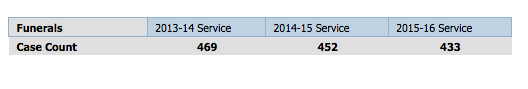

In 2015-16, 433 funerals were covered through DCS’ Employment Supports and Income Assistance program, not including those funded through the department’s Disability Support program. However, the department doesn’t track how many of these funerals were associated with unclaimed remains, or homeless individuals.

caption

The number of funerals covered through the department’s Employment Supports and Income Assistance program in the last three fiscal years.

If the DCS agrees to cover funeral costs, then the deceased is released to a funeral home.

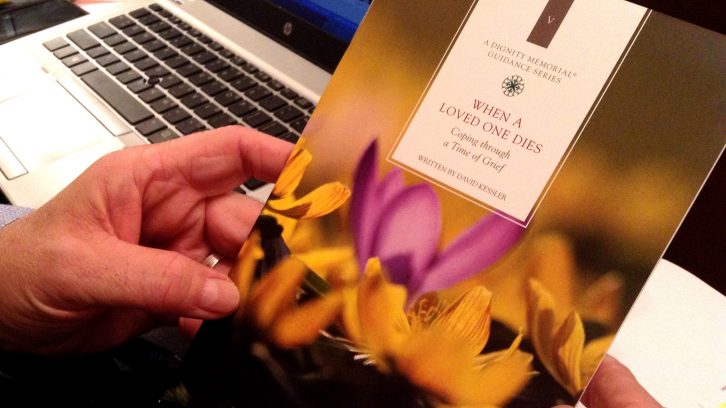

caption

Dwayne Isenor has encountered three unclaimed bodies this year and says only two of them had friends at their ceremony.

First, only a blood relative can identify a body, not a friend. Secondly, if there is no next of kin or designated executor, it’s automatically a burial. This is because the body must be identified for a cremation to be done.

“To cremate someone who wasn’t authorized, we can’t reverse that,” Isenor explains. “Say a family member does show up down the road, the body could be exhumed, identified and then cremated.”

Isenor has encountered three unclaimed bodies this year and says only two of them had friends at their ceremony. When nobody shows up for funeral services, Isenor and staff at the funeral home step in to pay their respects.

“You wouldn’t want to be that person that no one came to your funeral,” Isenor says. “We feel bad when there’s no one and we’ll go out of our way to attend the funeral. Sometimes family members show up at the 11th hour (and) sometimes they’re afraid they’re going to be on the hook financially. It’s sad, but we make sure we do the best job that we can.”

If a body comes in without any clothing, Isenor or a staff would go to Value Village and purchase clothing. If a friend wants to write an obituary, Cruikshanks will post it on their website free of charge. Isenor says they sometimes waive fees completely, if friends cannot afford to pay for anything at the service.

“We understand in our business (that) everyone needs a funeral, whether you’re rich or poor,” he says.

caption

Jeff Karabanow has been working with the homeless community for over two decades. The death of a client is something he encounters now and again.

“Homeless or not homeless, funeral services always touched me,” says Karabanow. “It always makes me reflect on someone’s life and their struggles. I’m touched by the communities that come out for these funerals and sometimes, the lack of community that comes out. The last one I went to (two years ago) had about 11 people.”

caption

Over 235,000 Canadians experience homelessness every year.

“You’re constantly in survival mode,” says Karabanow. “There’s no place for down time; there’s no place to heal or rest. When you’re living on the street, you’re constantly under the gaze of the public but you feel so distant from mainstream culture. It creates a sense of disbelief, of helplessness, of not being a part of something.”

Karabanow also points out there is a “criminalization of poverty,” as homeless people tend to be seen as outsiders.

“They tend to be viewed as the other, and they’re deeply marginalized,” he says. “Civil society does not accept them very well. We see very disrespectful and menacing conversations that people will launch at folks living on the streets (and) we also see more violent activities towards street people.”

According a study by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, and the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness (CAEH), there are over 235,000 Canadians who experience homelessness every year and 35,000 people are homeless on any given night. Karabanow says the street may be perceived as safer, depending on a person’s background, especially young people who’ve left abusive and exploitative environments. But, they soon they learn the streets are just as violent and exploitative.

Halifax has a history of disadvantaged people in poor houses and poor asylums, dating back to the early 1800s.

Cynthia Simpson is a historical researcher on Halifax poor houses built during the 18th and 19th centuries. The poor, people with disabilities and orphans were amongst those that resided in these institutions. Three poor houses were established on Spring Garden Road and South Street at this time, with numerous unmarked graves beneath them.

caption

A poor house on the corner of Robie and South Street, originally constructed in 1869. It was rebuilt after a fire between 1884 and 1885.

“The records are only as good as the record keeper,” she says. “They did purchase nameplates but it was never said whether or not the nameplates were used for inmates, or if they were used for the coffins that were sold to hospitals.”

Simpson says giving a deceased person dignity in death doesn’t have to be an elaborate gesture. It could be as simple as inscribing their name onto something.

“That they lived and have died, and are buried here; that to me shows a lot of dignity for that person,” says Simpson. “It’s disappointing for that number of people to have died at the poor house cemetery and there are no markers in the ground.”

Fairview cemetery and Mount Hermon cemetery are the only two city-run common ground cemeteries in Halifax and Dartmouth, respectively, where unclaimed bodies are buried.

“I try to not just gloss over or say empty words. It would vary as much as possible in wanting to give either hope or comfort to those who are left behind.” John den Hollander.

Depending on the deceased’s religious affiliations, den Hollander reads Bible verses, poems, or song lyrics at the ceremony. He’s careful in what he selects and tries his best to craft each speech to the person’s character and accomplishments, based on what he learns from friends.

“I try to not just gloss over or say empty words,” den Hollander explains. “It would vary as much as possible in wanting to give either hope or comfort to those who are left behind.”

The type of comfort or hope does vary.

“Some have burned bridges with family and friends,” he says. “Some are grieving not just because the person is gone, but because there wasn’t a connection maybe for the last couple of years, (or) because they chose not to get support, help or be in touch with family.”

caption

Depending on the deceased’s religious affiliations, den Hollander reads Bible verses, poems, or song lyrics at the ceremony.

“It’s a life cycle. Equally important as coming into this world, is going out of this world.”Dwayne Isenor.

Isenor describes his job as a calling and stresses that dignity in death is just as important as celebrating a new life.

“It’s a life cycle,” he explains. “Equally important as coming into this world, is going out of this world.”

He adds that it’s important for a person to have their life celebrated and to have closure, no matter who they are.

“Just because they’re homeless, doesn’t mean there isn’t a full circle of friends and loved ones,” he says. “Religious or non-religious, it doesn’t matter, that person deserves the utmost dignity and respect.”

caption

Prayer candles burn brightly in St. Mary’s Cathedral Basilica on Spring Garden Road.

“They just didn’t fall out of the sky; (they had) moms or dads or brothers or sisters, they came from neighborhoods, they had fellow workers,” he says. “It’s good to remember all the good times, but also to be there supporting because their life is never going to be the same again.”

About the author

Sarah Poko

Sarah Poko is currently a Masters of Journalism student at the University of King's College. Originally from Nigeria, Sarah has a keen interest...