The secret to being a full-time freelance journalist

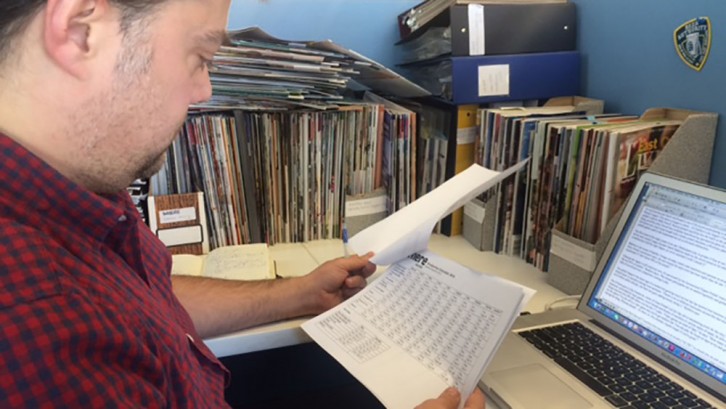

caption

Jon Tattrie is a successful freelance journalist in Halifax.Jon Tattrie has it – and he’s letting us in

Jon Tattrie heads down to the basement of his Bedford home, red coffee press in hand. His office is a small, blue-grey room, with a giant easel in the corner holding a blank writing pad. A little farther in there’s a bookshelf as tall as his six-foot-four-inch frame.

He sits down in a swivel chair, moccasin slippers planted firmly on the ground. He’s quiet as he waits for his two computers – one desktop and one laptop – to boot up.

Tattrie’s soundtrack of choice is a smooth electronic playlist from Songza. But every few minutes his two-and-a-half-year-old son Xavier’s giggles float down from the living room, blending in with the soft pulses and synths of the music.

“The perks of working from home,” Tattrie says, as he pours coffee into a flower-printed mug. “Fresh coffee and a cute baby upstairs.”

He is illuminated by orange light. The desk lamp spills it onto his fingers and another small overhead light warms his salt-and-pepper hair.

Today he’s working on his latest book pitch, organizing his ideas into chapters, preparing a blurb about each one to later send to his editor. Every so often, he slurps his coffee.

At first glance, Tattrie’s life looks easy – rolling out of bed into comfy clothes, making his own schedule and spending time with his family.

But being a freelance journalist is more difficult than you’d think.

It was a trip to Edinburgh, Scotland in 1999 that introduced Tattrie to the possibility of freelance journalism. He had just graduated from Dalhousie University in Halifax and needed a change of scenery, so he headed to Europe to find it.

Once in Edinburgh, he met someone who had made a career out of freelance journalism. He decided to spend time with him as he was “making his living interviewing interesting people and having fun adventures and writing about them.” That gave Tattrie the journalism bug.

After doing a one-year journalism diploma at Edinburgh’s Telford College and taking a side course in copy editing, he worked for a few Scottish newspapers as a copy editor, freelancing on the side. In 2006, he moved back to Halifax and got a copy editing job at the Daily News, until the paper closed in 2008.

Suddenly, he was unemployed.

For about six months he couldn’t get a permanent job. Competition was fiercer than ever – news outlets were revamping their business models and re-evaluating their staff positions.

He decided to try freelancing full-time, and ended up “making a job” out of it. Almost six years later, he’s still happy.

“I’m not hoping to one day get a staff job,” he says. “It’s just what I want to do.”

The business of freelance

In his first six months, Tattrie had almost no income. He spent his days pitching and researching the market, figuring out who uses freelancers and who had a freelance budget. He survived on employment insurance and savings. Once he got his foot in the door at several publications, it was easier to get consistent work.

But the freelancing market has changed since then.

Brian Ward, vice president of news content at the Chronicle Herald, declined an interview for this article. However, he said in an email that the Halifax paper is using fewer freelance writers than in the past.

caption

Senior editor Trevor Adams reviews the production schedule for upcoming issues of Halifax Magazine.“Freelance is one of the first places we look to cut when budgets come under pressure,” he wrote.

Magazines like Halifax Magazine and East Coast Living, though, have always relied on freelancers – and their publishing company, Metro Guide Publishing, has no plans to stop this practice.

“We don’t have any staff writers,” says Trevor Adams, Halifax Magazine’s senior editor. “For us, it’s never really changed. We’ve always been a freelance-heavy model.”

Tattrie is one of Halifax Magazine’s contributors, and has worked with Adams for the past five years. He says the fleeting nature of freelancing is not a deterrent. The job is what you make of it.

To be successful, Tattrie says freelancers should focus more on what the current market needs, rather than trying to find a market that supports what a freelancer personally wants to write about.

Tattrie’s success stems from his freelance business model.

He started out by taking the Self Employment program offered by the Nova Scotia government, which teaches people how to start their own businesses. But he also learned a lot just by sitting next to someone who was trying to open a sushi restaurant.

The restaurateur was realistic about his business plan: he knew he wouldn’t make a salary for a couple of years, and he wasn’t going to complain about it while he was getting on his feet. Tattrie thinks freelancers are too focused on low wages and should be restructuring their business models to suit the market.

“Rather than thinking, ‘Why don’t you give me more money?’” he says, freelancers should approach business like, “‘If that’s what you’re offering, either I find a better deal, I negotiate with you for a better deal, or I accept the deal.’”

Managing work

In a typical week, Tattrie works at the CBC for a couple of days and writes some of his newest book on his days off. A couple of times a month he teaches writing courses at Dynamic Learning, a corporate training company in Halifax. The CBC is what he calls his “anchor client;” he’s freelanced there since he started out.

He keeps track of his work in a Google Docs chart. In mid-November 2015, he had 13 articles on the go, for publications like Metro, Business Voice and Halifax Magazine. Most were due in the middle of December, on top of his CBC commitments and his teaching. The workload varies throughout the year; he might work on anywhere from six to more than 20 projects at the same time.

caption

Jon Tattrie signs copies of his books Limerence and Day Trips from Halifax in the book section at a Halifax grocery store.“It is stable, in that I try not to let any one client keep more than about 30 per cent of my work,” he says. “Even if I lose a big client, I still have 70 per cent of my clients, 70 per cent of my work, and I can rebuild from there.”

Finances weren’t as much of a concern to Tattrie when he was single and starting out. But since he married his wife Giselle in 2010, and had Xavier in 2013, maintaining a steady income has become something that can worry him.

But he says that at this point in his career, he makes the same salary as most staff journalists. According to PayScale.com, a website that offers data about salaries for almost every occupation, that’s about $47,000 a year.

He’s not the sole breadwinner either. His wife is also a freelancer, and the two balance their workloads between spending time with Xavier.

“It’s definitely not for everyone, but if you know what it’s like and you know what fits with your life, it can work,” Tattrie says.

Making a living

Statistics about the number of freelance journalists in Canada are generally hard to come by, and most are not up-to-date.

Nicole Cohen, an assistant professor at the Institute of Communication, Culture, Information and Technology at the University of Toronto-Mississauga, says it’s because the title of “freelance journalist” or “freelance writer” is very fluid. There are so many different freelance situations – temporarily between jobs or part-time, for example – that it’s hard to accurately keep track of everyone in the field.

Data from the 2011 Canadian census and National Household Survey say that out of 12,965 journalists in 2001, 2,100 were self-employed. In 2011, 1,970 journalists were self-employed out of 13,280. That’s a decline of 1.4 per cent within a decade.

When Cohen did her own survey of 200 freelancers for her 2013 dissertation, she found that the wages have been stagnant for roughly the last 40 years. But, in contrast with the census figures, she found there are a lot more freelancers than there ever used to be.

“They really love their jobs and the work they do,” she says. “But when you look at material conditions – pay, hours, benefits, security – you realize how precarious it is. In order to make a decent living, you have to work extremely hard.”

In 2006, the Professional Writers Association of Canada (PWAC) reported that 99 cents per word was the highest a freelance journalist could get for his or her work in Canada, with 15 cents per word closer to the bottom.

Reader’s Digest currently pays one dollar a word to its freelancers, while Halifax’s alternative newsweekly, the Coast, pays 15 cents a word.

Halifax Magazine pays 35 cents a word, which Adams says puts the magazine “in the middle of the pack.” But he says they’re closer to the bottom when compared nationally.

“I understand the writer’s perspective and I would give anything to be able to raise those rates,” Adams says. “It’s a conversation I have with my publisher every single year.”

Freelancers are often asked to work for less than what their time is worth.

Don Genova, president of Canadian Media Guild’s Freelance Branch, recalls when he was offered an opportunity to write a list of 10 restaurant reviews for the YellowPages app in Victoria, B.C. Each review would be 500-850 words, and he’d be paid $50 for the whole list. Genova was insulted.

“To think that a professional writer would work for as little as $50 for 850 words is just ridiculous, and yet I’m sure they’re finding people who will do it,” he says.

The YellowPages editor was quick to tell Genova his profile would be on the app and it would drive traffic to his website and blog, but Genova refused the job.

“It’s that old thing: ‘You’ll get lots of exposure,’” he says. “The standard freelancer’s answer to that is, ‘People die of exposure. You can’t pay the bills with exposure.’”

But rates aren’t something Tattrie has ever really been concerned about.

“I think the biggest problem freelancers have is ‘woe-is-me-ism,’” he says. “(Corporations are) not putting a value on you as a person or your creativity; they’re saying, ‘This is how much the magazine earns through ads, this is how we can pay everybody, this is what we can offer you.’ It’s not personal, it’s business.”

Keeping copyright

In 2011, the Chronicle Herald changed its contract with freelancers, stating it would own all copyright on work printed.

The same thing happened in 2013 with Transcontinental Media, the company that at that time published magazines like Elle Canada and Canadian Living.

“Freelancers make their living by taking one idea and selling it in many places in different formats. A lot of these contracts prevent them from being able to do that,” says Genova.

Freelance unions are trying to change that.

“There’s lots of work to be done, lots of people to do that work, but there’s not often a good matchup of those two things because it’s really hard to get paid fairly,” says Leslie Dyson, president of the Canadian Freelance Union. “We want to bargain on behalf of freelancers.”

Genova says CMG’s Freelance Branch won’t bargain, but “We can give you some advice so that you recognize what you’re getting into. We’re trying to at least improve the awareness.”

Unions sound like a good idea for some freelancers, but if you ask Tattrie about them, he scoffs.

“I’ve always thought it was a bit of a contradiction,” he says. “The idea of unionizing independent people just doesn’t seem to make sense. But I’m always open to seeing if it does work.”

Tattrie swivels away from his desk and gets up to take his lunch break. It’s about noon, and it’s much quieter now – Xavier is napping and the Songza playlist has been paused.

Within the grey of his office walls, his computer screens glow. He doesn’t turn off the light; a touch of orange still holds onto his clothes. He grabs his mug and heads upstairs. The cursor on his screen blinks; it waits for him to come back.

And he will come back. There’s always more work to be done.

Main photo: Jon Tattrie is a successful freelance journalist in Halifax. Photo by Maia Kowalski

D

Don Genova

B

BCF