Nova Scotia moves VLTs around, buys out legions and keeps the money flowing

Some VLT bars now have more machines than allowed anywhere else in Atlantic Canada

You might call it the VLT shuffle.

The machines that have been called the “crack cocaine of gambling” have been regularly moved around to pull in more money, though the Nova Scotia Gaming Corporation prefers to say it’s providing an “optimized offering.”

For years, VLTs in the province—not including those on First Nations—have been subject to a declining cap on numbers.

That’s the policy.

But an investigation by King’s journalism students has found that the gaming corporation, and its VLT operator, the Atlantic Lottery Corporation, have worked to beef up the returns on the ones that remain, partly to hit provincial government revenue targets.

How do they do it? When a bar or restaurant closes temporarily, machines are moved to other locations. When given up voluntarily by bars, clubs or legions they are placed in other locations. And sometimes, gaming authorities have forced less busy bars to give up machines, and even paid legions and other non-profits to allow them to be relocated to higher traffic venues. The machines themselves have been updated over the years as older ones have been replaced with more appealing VLTs.

Today, the largest VLT locations in Nova Scotia (excluding First Nations) exceed anything allowed in any other Atlantic province. As well, the Dooly’s chain now accounts for one in six non-First Nations VLTs in Nova Scotia.

While gaming corporation president Bob MacKinnon insisted in an interview that making money isn’t the first priority—he said social responsibility is–the various policy documents of the gaming corporation and Atlantic Lottery do reference meeting revenue targets as a motivation in managing the system.

Asset management

The Atlantic Lottery Corporation has had a policy called “asset management,” in place in one form or another since 2002.

“(Asset management) is the on-going monitoring of all terminals in for-profit sites across Nova Scotia and the adjustment of terminal counts at the individual site level to ensure the assets are put to best use,” the gaming corporation’s internal attrition policies say. “In a scenario where asset management is not conducted, there would be instances of terminals sitting idle in some sites while in other sites, players would be waiting to play.”

This gives an incentive to businesses to “make ongoing improvements to their sites,” the policies say. As well, “NSGC and Atlantic Lottery regard this practice as a critical element in meeting revenue targets and therefore, meeting budgeted payment to province (sic).”

“We do look at the fleet of VLTs to make sure that they’re in the right place,” MacKinnon said. “There’s changing demographics, changing economics in one community versus another, so some community may experience population or economic declines, while other communities may be growing, so it would be typical you don’t need 10 VLTs in this community, so you might move them over to another.”

The stick

The policy has resulted in some forced removals of VLTs.

Atlantic Lottery has an explicitly stated policy that applies only to Nova Scotia and allows it to remove VLTs from locations it deems to be not earning sufficient revenues and add VLTs to other locations that do better.

The retailer policy—“retailer” is Atlantic Lottery lingo for a business or non-profit hosting VLTs — is buried two layers deep on the Atlantic Lottery website, in a section labelled “retailer zone.” It allows the removal up to a third of a location’s VLTs in any one-year period if it falls into the bottom third of a list ranked by financial performance in quarterly reviews. If a retailer has two or fewer VLTs, it can lose them all.

VLTs can also be added to retailer locations, with Atlantic Lottery having the final say on where they will go based on criteria such as previous financial performance of VLTs at that location and anticipated performance if new VLTs are added, “the potential of various retailer locations to generate the highest incremental revenue” and “market conditions…including consideration of player demand,” according to the Nova Scotia VLT retailer policy

The policy also said it will “assess current and future market conditions to optimize revenue potential for the Nova Scotia video lottery program in a sustainable and socially responsible manner.”

According to numbers released by the gaming corporation under access requests, 34 VLTs were removed from 32 retailers from 2018 to 2020 pursuant to the VLT retailer policy for financial performance, and 52 added to 30 retailers.

Letters

Some retailers contacted for this investigation indicated they had received letters from Atlantic Lottery warning them about poor performance. Such “underperforming notices” are mentioned in the retailer policy.

George Jbelli obtained three VLTs for his Revana Pizza operation in Truro after another pizzeria nearby closed in 2016 because its building was going to be demolished for a new highway roundabout. He said the owner of the business that was about to be demolished approached him and asked if he would be interested. It was an expensive investment for him, and that included $65,000 for renovations to prepare for liquor service and the VLTs, including installing a new wall and an outdoor patio.

“I wanted them to have a little more privacy,” he said. “People want to play them; they don’t want to have you look at them. I did what I did…hoping it would generate more income over the years.”

caption

King’s Investigative WorkshopThe province approved Jbelli’s business for a liquor license transfer and Atlantic Lottery gave the green light for the VLTs, but in a 2020 interview he said he knew he could lose some or all of the machines if they didn’t perform well enough. He’s not happy about that because he says he wouldn’t have spent all the money and taken over the liquor license if it hadn’t been for the VLTs.

“We’re a small business, you know. You’re going to buy a slice of pizza, and we’re going to make a little bit of profit. You’re going to buy your bottle of beer, and we’re going to make a little bit of profit. You’re going to sit and play the machine, and I’m going to make a little bit of profit. So, I’m banking on those three things.”

He pays a little over $100 a year in licensing fees for each machine. VLT retailers receive a commission of 25 per cent of net revenues up to $400,000 and 15 per cent after that, minus an amount payable to Atlantic Lottery, according to the retailer policy. Net revenues is the government’s way of describing the money players lose.

The carrot

Atlantic Lottery Corporation’s asset management program does not apply to legions and non-profit organizations. VLTs in non-profits have been protected ever since the John Hamm government’s gaming strategy shielded them from the initial cull of 1,000 VLTs starting in 2005.

But while those VLTs are still officially protected, there is nothing to stop non-profits from giving them up voluntarily or being given an incentive to do so.

Several legion branches told us they were paid $10,000 per machine to hand back VLTs, and in its 2017-18 annual report, the Lottery Corporation noted a $1.2 million increase in VLT revenues in Nova Scotia, “driven by a voluntary reallocation initiative of community minded and legion terminals to locations with more player demand.”

We sought more information through an access request to Nova Scotia Gaming.

In all, according to the statistics released, 41 VLTs had been relinquished by 22 legions and other non-profit locations by July 2020, for a total payout of $410,000, a trivial amount compared to what those VLTs can earn even in one year in a higher-demand location.

“We only had three VLTs and so that money we automatically put into our investment funds,” said Paul Murphy, first vice president of the Wolfville Legion. The money was used for some initial cosmetic improvements to the legion in advance of a much larger renovation.

caption

Paul Murphy of the Royal Canadian Legion Branch No. 74 in Wolfville.And the move seems to have had a salutary effect.

“We had more revenues coming in steadily by the end of 2019, about 18 months after we got rid of the VLTs,” he said. Membership that had dwindled to 62 was back up to 142 in mid-December 2021.

The Wolfville Legion even received an award in 2020 from Gambling Risk Informed Nova Scotia, for ridding itself of the addictive machines.

MacKinnon of the gaming corporation said some legions have had economic or other challenges and “may want to not have VLTs, and we have taken that as an opportunity to, if they wanted to remove the VLTs, that to make a payment to give them, afford them, the opportunity to do so and we can redeploy them into other sites where they might be needed.”

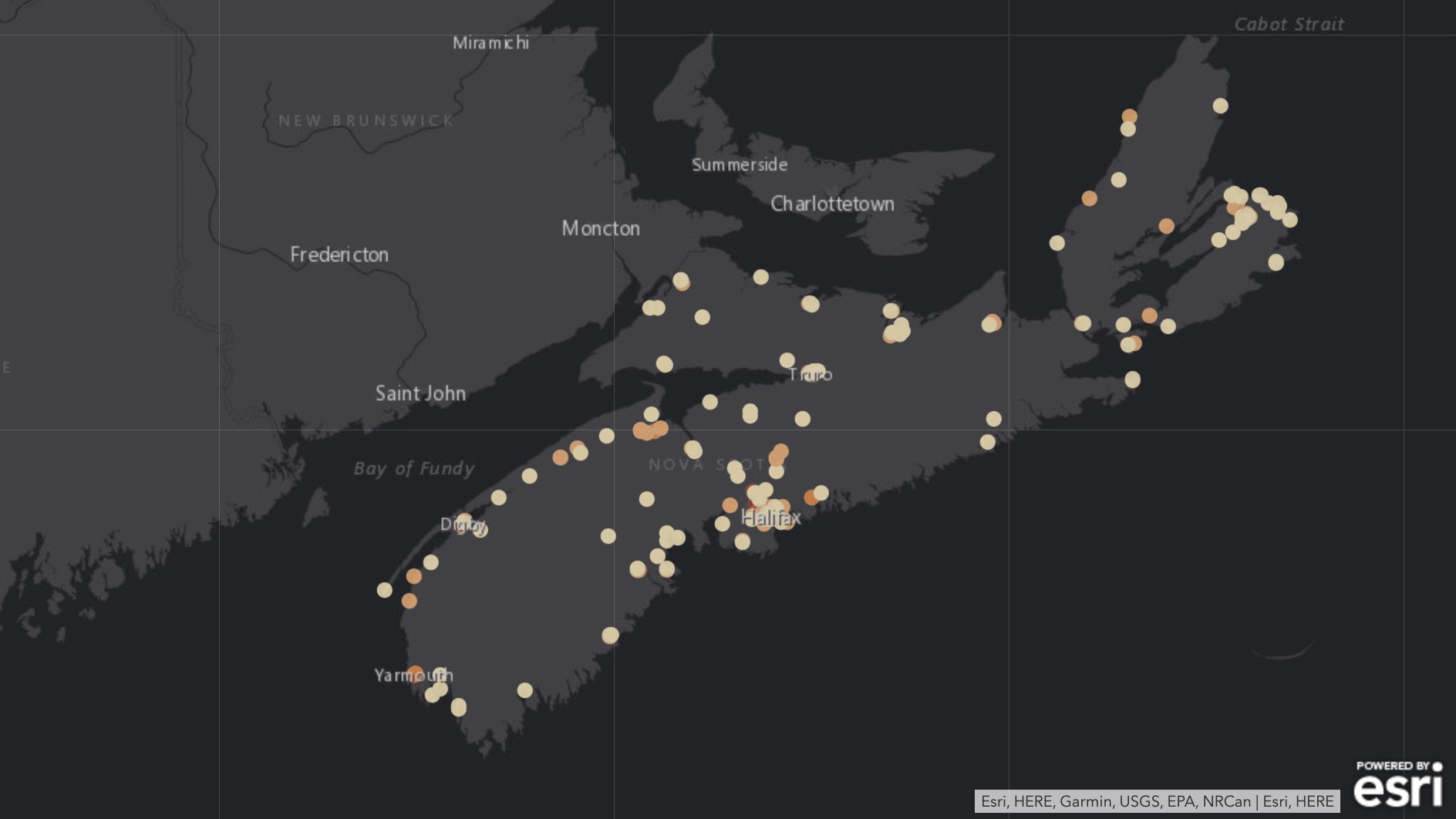

This map shows the locations of VLT businesses and clubs in February 2012 and December 2021. Swipe to the right to see 2012 locations and to the left to see 2021. The darker the dot, the more VLTs are located there. Click on a dot to see how many.

Growing concern

One trend that is clear in the numbers is that VLT locations, on balance, are getting larger. That is something the gaming corporation itself anticipated in its attrition policies. “Natural site consolidation and growth is expected as terminals are moved from low to high-performing sites and lower-performing sites cease operation.”

Comparison of a list of VLT locations from February 2012 to a list at the end of 2021 shows that the number of VLT locations shrank and the average number of VLTs per location grew. Almost all the growth was in commercial locations, which slightly outnumber non- profits overall.

A few got a lot larger.

Seven per cent of all VLTs were in locations with 20 or more VLTs in 2012, with the largest location having 22. By the end of 2021, that had nearly tripled to 20 per cent. The number of such locations had gone from seven to 15. (A 16th such location, the Clay West Bar and Grill in Bayers Lake, had 26 VLTs at the end of 2019 and closed late last year. It is being developed into a brew pub by the operators of the Big Leagues Pub in Cole Harbour, an existing VLT venue. Big Leagues owner James Latter said he will have VLTs in Bayers Lake, but didn’t know how many.)

As well, about one in six Nova Scotia VLTs — not including those on First Nations—was located in an establishment under the Dooly’s banner by the end of 2021, according to data provided by the gaming corporation. That’s up from one in 10 in 2012. Dooly’s locations added more than a hundred machines in that timeframe, according to government data. The group is the largest single commercial operator of VLTs in the province, just short of the number in the far more numerous legion branches. Some Doolys are franchises. Dooly’s did not return calls for comment.

The largest location in Nova Scotia at the end of 2021 was the Dooly’s on Kempt Road in Halifax, with 35. In fact, six VLT locations, including four Dooly’s, were so large at the end of 2021 that they exceeded anything allowed in the other Atlantic provinces. New Brunswick allows no more than 25 VLTs per location, PEI 10 and Newfoundland and Labrador five, according to the Atlantic Lottery Corporation. There is no limit in Nova Scotia.

caption

Dooly’s on Kempt Road in Halifax is the largest non-First Nations VLT location in Nova Scotia.MacKinnon declined to comment specifically on Dooly’s, but insisted that making more money isn’t the first goal for the gaming corporation, but social responsibility. He also noted the 2011 gaming strategy had a goal to reduce the stigmatization of VLTs and VLT players.

“If we know a site has renovated, it’s bright, it’s got many entertainment offerings and staff are very well trained in responsible gambling, that site may be one that would receive VLTs from other sites that may not have been able to make investments in their VLTs.”

More appealing VLTs

VLTs have been updated as well. In 2019-20, for example, 200 VLTs in Nova Scotia were replaced and Atlantic Lottery recently signed a contract to further modernize its machines in Atlantic Canada.

Andrew Younger, a gaming minister early in Stephen McNeil’s Liberal government, said he was bothered by the push to bring in newer and more appealing terminals.

“Atlantic Lotto Corporation’s job was to increase lottery revenue. And that’s their mandate. And so, they had a mission to replace underperforming VLTs with games that were more attractive and more popular,” he said. “And it always struck me that that was antithetical to the point of trying to have attrition or reduce the amount of gaming.”