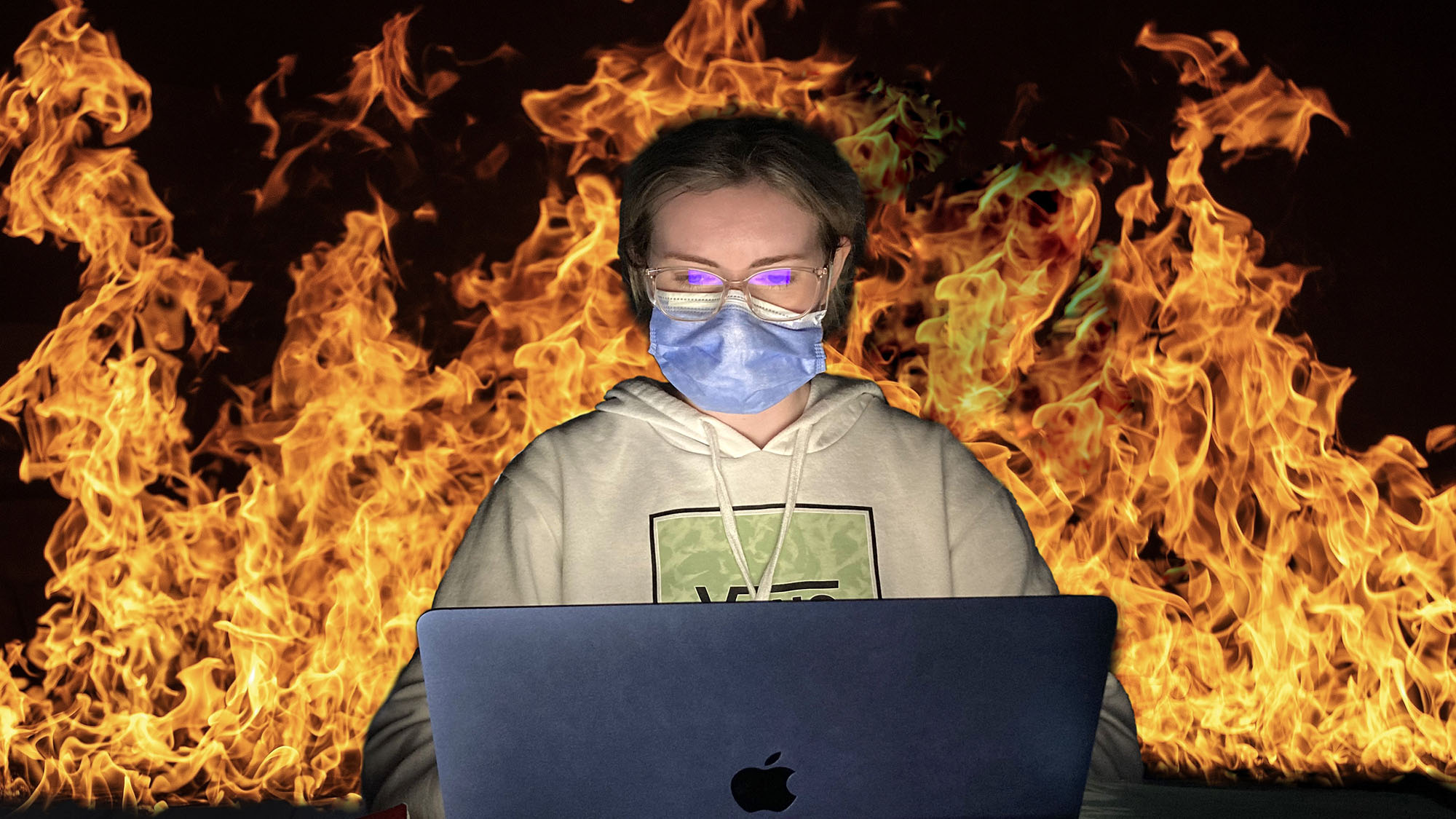

Hot and bothered

caption

More journalists are feeling the burn while covering COVID-19 during the pandemic.How burnout is affecting journalists during the pandemic

Emails were Seth Klamann’s morning alarms. The education and health reporter was on the job every waking moment once the COVID-19 pandemic was declared.

Instead of enjoying his lunch breaks, he was studying the latest virus numbers and trends in Casper, Wyo. In the middle of running errands, he’d pull out his laptop in the car to file stories for the Casper Star-Tribune.

“I brought my laptop everywhere. For a while, I slept with it open on the floor next to me,” says Klamann.

He thrived off the thrill of breaking news after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the pandemic on March 11, 2020. But then he moved to Colorado in October. He started a job with the Denver Gazette. That’s when the weight of working the endless virus news cycle began to set in.

Klamann covered more than pandemic-related stories. Some were grim; he wrote about sexual abuse, suicides and a mass shooting in 2021.

Sleeping became difficult. Klamann began using a “substantial amount” of marijuana after shifts. The combination of stress, bringing work home and weed — which he dubbed “a bad pattern on steroids” — began chipping away at his well-being and relationships outside of work.

Then he found out a source for a drug-related story overdosed and died in July 2021 — only two days after they spoke.

“I was pretty close to leaving journalism entirely after that.”

The drain is real

Journalists everywhere, from Klamann’s car to Canadian newsrooms, are being forced to endure the largest global health emergency since the 1918 influenza pandemic, with the added stress of covering it.

The crisis is forcing discussion of mental health, on and off the job. Public health restrictions. Isolation. A news cycle saturated with sickness, death and tragedy. These are just a few factors influencing the wider discussion of how reporting on COVID-19 is threatening journalists’ health.

Changing work patterns, such as flexible or remote arrangements, are common in pandemic journalism. The ensuing isolation, dreary routines and unrelenting coverage of negative news, for many, is leading to greater risk of depression, addiction, excess stress and even symptoms of trauma.

Burnout is one of these consequences.

The Taking Care Report, released last May by the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma, dove into the state of mental health in newsrooms during the first 20 months of the pandemic. Carleton University journalism professor Matthew Pearson co-authored the report. He describes burnout as when “someone’s not really excited or finding a lot of joy in what they’re doing.”

Two-thirds of the report’s respondents suffered negative effects from working on trauma-related assignments, such as COVID-19 coverage — 80 per cent of them say they also burnt out in this period of time.

“Regularly witnessing human suffering puts media workers at elevated risk of compassion fatigue, burnout and traumatic stress,” the report reads.

The definition of trauma in the report includes secondary, or vicarious, trauma. This is when one experiences trauma after being exposed to the trauma of others. In a newsroom, examples include listening to a victim’s account or playing back distressing footage.

The effects outside Canada are clear, too. The International Center for Journalists surveyed journalists from 125 countries — mainly from the U.S., India, Nigeria, the U.K. and Brazil — with 38 per cent of respondents reporting exhaustion and burnout.

Dread and departures

On Sept. 30, The Atlantic’s science reporter Ed Yong announced he was taking a six-month sabbatical from journalism, citing burnout. He won a 2021 Pulitzer Prize for his “lucid, definitive pieces.”

In a Twitter thread, he noted from his work three “roads” burnt out people follow: commit further to the “duty and mission” of the job, “find community,” or take a break. Yong considers himself on the third road — stepping away — to focus on community.

“I’ve done the first for as long as I can.”

Researchers have attempted to measure distress in journalists during the pandemic. A July 2021 study uses the presence of “clinically significant emotional distress” as an indicator of burnout in the field. More than 80 per cent of journalists who participated showed evidence of this type of distress.

Workloads and workplace structures have long influenced burnout. Former Seattle Post-Intelligencer web producer Callie Craighead saw her news team shrink to two employees from eight. She took on the work of several departed colleagues at the expense of her mental and emotional health.

“I felt I’d constantly be on Twitter or other news sites, looking for what we were missing,” she says. “It didn’t ever feel like there was off time.”

Craighead associated feelings of anxiety with her burnout. Others, such as former Daily Beast lead COVID-19 reporter Olivia Messer, experienced extreme symptoms from dehydration to suicidal thoughts.

“Covering COVID-19 is trauma reporting,” Messer wrote in an article chronicling her departure from the industry, “The COVID Reporters Are Not Okay. Extremely Not Okay.”

What the health?

The term “burnout” is used broadly to describe feelings of stress at work.

The WHO recognized burnout for the first time as an “occupational phenomenon” in 2019. It defined burnout as “a syndrome … resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” Burnout is recognized in three ways: emotional exhaustion, cynicism or disconnection from one’s work and “professional efficacy,” when one has a hard time completing duties.

Dr. Dayna Lee-Baggley is a Halifax psychologist who has studied workplace health during COVID-19. She says individuals experiencing burnout are at greater risk of depressive or substance use disorders.

“What really stands out about burnout now is that everyone’s burnt out. It’s probably harder to find people who are not burnt out,” says Lee-Baggley.

Rest is not burnout’s antidote. Rather, it’s “reigniting a sense of meaning and purpose” in what one does.

Lee-Baggley says employers may encourage staff to practice self-care, but it’s not enough. “There are workplace factors that we know will cause burnout,” she says. “When organizations take steps to address those workplace factors, you’re actually helping way more people.”

Presence is a gift

A May 2021 study by Gretchen Hoak, an associate professor of journalism at Kent State University, suggests much of a journalist’s job satisfaction comes from working in-person. She notes an “unexpected loneliness” newsroom employees felt after shifting to remote work.

“The newsroom may be the place where journalists receive much-needed intangible support connections that keep them going when stressed,” Hoak’s study reads.

News director and station manager Rhonda Brown supervised her Global News team in 2020 during the largest mass killing in Canadian history: the Nova Scotia attacks. A comment from a coworker remains with her.

“He said, ‘This is the time that I would really love to go out and have a beer with my colleagues and just talk about what happened,’” Brown recalls. “‘But we can’t.’”

Emotional support became crucial. Her team in Halifax had its most traumatic assignment ever, compiling heartbreaking reactions from victims’ families and gruesome crime scene details – all while steering clear of COVID-19.

Brown helped organize group video chats soon after to share supports for newsroom employees. One expert was a trauma specialist.

“For a lot of our journalists, they were still fairly early in their career,” Brown says. “They may not have covered this kind of event before – certainly not on this scale.”

Managing chaos

The onus is on media companies to provide support for employees.

Jennifer Smith joined the Vernon Morning Star in 2004 when its B.C. newsroom employed 13 people. That number has fallen to three thanks to print cuts; others left before and during the pandemic.

Smith, an editor and reporter, has watched colleagues deteriorate into burnout. She’s an advocate for mental health days. Morning Star employees get five per year. If anyone on staff needs more support, Smith says she grants accommodations with no questions asked. Openly using the term burnout helps promote mental health in her newsroom.

“That way, one of us can help and ask ‘Hey, what can I take off your plate?,’” Smith says.

With newsrooms forced to cut coverage or delegate responsibilities to other journalists when someone leaves, remaining staff often feel helpless. Former Seattle Post-Intelligencer journalist Callie Craighead says overload is one of the reasons she left.

Her manager ”understood what the problems were, but couldn’t really stop them,” Craighead says, adding she was encouraged to take time off after long shifts. “But I’m doing the work of three or four people. My boss knows that. Does my boss’s boss know that?”

Pool skimmers

It took Denver-based reporter Seth Klamann months of therapy, reflection and meditation. He spent a few days at his parents’ lake house, where he retreated soon after his source’s death.

But he soon rediscovered his place in journalism.

Now reporting for the Post, Klamann continues to practice key routines in his recovery from burnout. Ritually, he deletes the email app from his phone after every shift. He also cut back on marijuana.

Klamann continues learning how treatable the condition is. His accumulation of stress inspired an analogy he embraces: viewing his brain as a pool.

Recovery “let me scrape all the scum off the top of the pool so I could get a sense of what’s going on underneath it,” he says. “The scum is s—t I’ve gone through at work over the past 18 months. But how much of it contains deep underlying issues I need to address beyond work?”

Correction:

About the author

Luke Dyment

Luke Dyment is a Halifax-based reporter from Prince Edward Island. He has written for the Globe and Mail, The Signal and the Dalhousie Gazette....