One path out of Nova Scotia’s homelessness crisis

Shelter villages help ease transition to permanent housing

caption

Nick Aligiannis, shown here in an interview conducted in a nearby library, moved into one of the shelter village units in Clayton Park earlier this year. His goal is to move out in 90 days.Nick Aligiannis arrived in Clayton Park one afternoon in March.

Carrying all his belongings in four bags, he was heading to his new home: a 70-square-foot shelter. It’s one of 40 in a village built by the provincial government for the city’s growing homeless population.

Inside, there is just enough room for a mattress, a small desk, some shelves — and a door that locks. He had broken up with his fiancee and ended up homeless after he lost his business last Christmas.

He’s grateful about having his own space.

“When I had the opportunity to come here, I kind of hit the ground running.”

Clayton Park is one of Nova Scotia’s shelter village locations. Another site in Lower Sackville hosts 19 units.

A year ago, in Lower Sackville, over 170 residents packed a community hall to express their concerns.

“In your right mind, no one would place it amongst our children,” said one resident. When one resident expressed support, others argued tensely.

The shelter is run by Beacon House, a local charity that has operated for 40 years.

“It was one of the most traumatizing nights of my life. I never expected the amount of hatred in the room,” said Beacon House CEO Mel Roberts. “We did this not because it’s our career choice, but because there is a problem.”

That problem is growing homelessness.

Based on an analysis by The Signal, two cities in Nova Scotia — Sydney and Halifax — had the second- and third-fastest growing homeless populations among 45 communities across Canada – ahead of cities like Vancouver and Toronto, only behind Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.

In Sydney, the number of homeless people nearly tripled. In Halifax, it rose by 168 per cent. The numbers are based on what are known as PiT counts, or point in time counts co-ordinated by the federal government. Communities are invited to number their homeless people on a single night.

As the map below shows, from 2018 to 2020-2022, Nova Scotia recorded an 182 per cent growth rate in homelessness, the highest among 11 provinces and territories. Data was only available from 2018 for Quebec and Nunavut.

Point in time counts growth rate by province (PiT 2018, PiT2020-2022) https://arcg.is/Pjnq90

Source: Statistics Canada, Boundaries Canada

Note: Data is based on 45 communities across Canada. Some provinces have more community participation than others.

Another way of counting the homeless is the By-Name List compiled by the Affordable Housing Association of Nova Scotia. In 2022, that list counted about 500 homeless people. Now, it is over 1,200.

Jeff Karabanow is a Dalhousie University professor who studies homelessness and poverty. He said there are a couple of reasons for the increase.

“One is our housing costs have skyrocketed more than any other province. Second, this is a perfect storm where we’ve had such disinvestment of the province in social housing that it’s coming up now. Third we’ve seen quite a large increase in people within Canada moving to Nova Scotia during and after COVID,” he said in an interview.

A new approach

In 2023, the Nova Scotia government announced it planned to spend $7.5 million to buy 200 shelter units from a U.S. company. They were placed in six locations across the province, including Clayton Park and Lower Sackville.

In an interview with The Signal, Scott Armstrong, minister of opportunities and social development, said shelter villages are one of the many approaches the government is using to tackle homelessness.

Shelter village locations in Nova Scotia https://arcg.is/1jmKWn2

Armstrong said the province took note of the issue as the numbers of homeless people increased.

“We looked across other jurisdictions who had suffered high levels of homelessness and looked at best practices. The shelter village approach is highly supported in other areas across North America and Canada.”

The project offers free temporary housing with private rooms, meals, hygiene facilities, and services like mental health support and help finding permanent homes for people like Aligiannis.

Armstrong said the budget to run these 200 shelter units for 2025-2026 is $13 million. “It’s hard to say $13 million is cheap, but supporting those people, that would be a relative, I guess, a feasible cost.”

caption

The shelter village in Clayton Park, where Nick Aligiannis moved in March.Shortly after moving into his new home, Aligiannis fell asleep. For the first time in a long time, he could sleep well.

“I used to live in a warming centre in Toronto. It is like half of a gymnasium of a high school. Eighty to 100 people live in it. No shower facilities. Police are there and people are drinking. I was just depressed,” he recalled.

Aligiannis came from Toronto. He said he was cheated by a friend and lost everything last Christmas.

“There was so much miserable stress and bad memories.”

Aligiannis left Toronto, bringing only a bag — and a puppy. A friend drove him to Nova Scotia.

After staying for a couple of nights at his friend’s place, Aligiannis moved to the dorm shelter at Beacon House in Lower Sackville. There he asked shelter co-ordinator Joe Deagle if he could live in a private home in the adjacent shelter village.

“Joe is absolutely amazing. I don’t mean to get choked up right now. But he has so much pull and power. He wants to help others. He made the phone call the next day. I had an interview and four days later, I moved in,” said Aligiannis.

At the time, Beacon House’s own shelter village was full, so Aligiannis was referred to the one in Clayton Park. He said he wants to be a normal person in society, and this is his last chance.

Deagle was happy to arrange the move.

“I’ll do whatever I can to help people — as long as they show they’ll help themselves,” he said.

Not everyone adapts as well as Aligiannis.

Roberts said she had a couple of residents of the shelter village who asked to move back to the dorm shelter. She also had folks who came from encampments who struggled to adjust.

“They’re like, ‘I wanted this so much, but it’s so quiet. I’m so alone and it’s getting into my head.’ “

She finds that “If you lose your housing, the faster you can get yourself on the by-name list and referred to a program or shelter village, the easier that transition is.”

According to a Statistics Canada survey in 2021, one in ten Canadian households experienced some form of homelessness in their lifetime. In 2023, the annual impact report of the Ottawa Mission, a shelter provider in Ottawa found that, on average, 27 people slept on chairs in their lounge each night since there were no extra beds or mats.

Karabanow believes shelter villages offer people a sense of dignity. “This is for a population that’s deeply traumatized and it’s a very good beginning of a healing process.”

Aligiannis said he was naïve about Nova Scotia before he arrived. “I didn’t even know you guys had condos here. I thought it was like the bush.” Now he has his Nova Scotia ID and calls himself Nova Scotian.

However, the project raises eyebrows in various locations.

In 2023, during a session in the province’s legislature, then-community services minister Brendan Maguire responded to criticism of poor public consultation over the housing crisis.

“A lot of people who push back will be the same people who will run online and say, we need to do something about housing, we need to do it now,” he said.

“We’re in a housing crisis. There is an easy way to get stuff done, that is to build.”

Renee George comes from Lower Sackville. She is mother to a 6-year-old boy. She said she understands homeless people’s needs — her own mother was once homeless. But she wonders if the shelter should be put so close to a high school. Some parents told the media their children found needles nearby.

In September 2024, then-Clayton Park West MLA Rafah DiCostanzo said the project raised concerns, due to proximity to a high school and three athletic facilities.

“When the province tried to open these villages, the biggest barrier was there was not enough provincially owned land,” said Beacon House’s Roberts. Their site was chosen because “there’s already a shelter there and the diocese was willing to let the government use the property, rent free.”

“They all watched the news,” said Roberts, referring to the shelter residents. “Some have gone through their own shit and don’t care what other people think. Others, especially those who are newly unhoused, are horrified that people would hate them like that.”

She encouraged shelter residents to engage with the community by taking a walk by the beach or visiting the library. Some remained reluctant.

Deagle said Beacon House has regulations and rules. All their homeless guests need to sign off on a good neighbour policy. People who can’t follow will be asked to leave.

“We don’t get as many angry emails as before,” said Roberts after running the shelter village for a year.

Path to permanent housing

Aligiannis recently got a job in construction. He said he understands local parents’ concerns. He works 10 hours a day and his goal is to move out of the village, find permanent housing and buy a car in 90 days.

Armstrong said some of the homelessness is due to a lack of housing supply.

“Nova Scotia has for the first time in 45 years seen a real increase in population. For years, the population of Nova Scotia was 950,000. Now it is over a million. We had to give housing a chance to catch up and have places for people to live.”

On Feb. 13, Growth and Development Minister Colton LeBlanc announced that 242 new public housing units will be built in various communities, at a cost of $136.4 million, the province’s largest ever in new public housing.

Roberts said in the last couple of months the homelessness crisis has eased slightly because the provincial government has streamlined many housing projects. But it’s a constant battle.

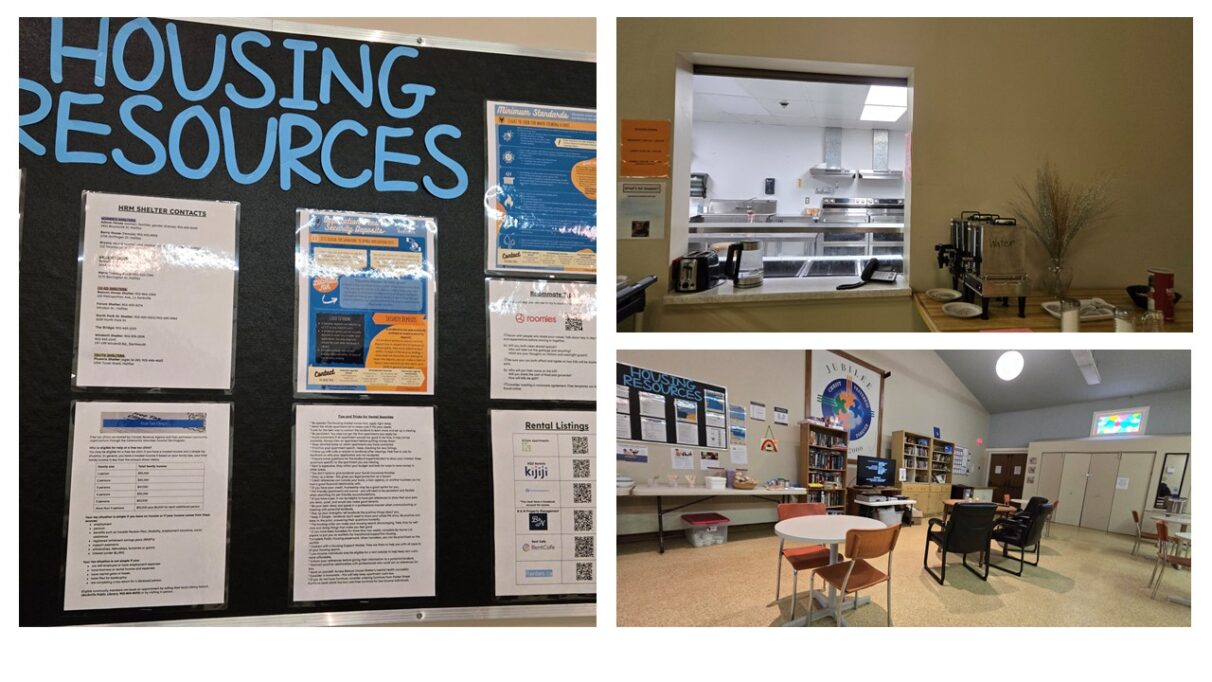

caption

The interior of Beacon House’s dorm shelter in Lower Sackville has a lounge area and information on acquiring a place to live.On a recent Friday morning at Beacon House, several people gathered in the dining room either watching TV or using the computer. Deagle said it’s not easy to find permanent housing for his guests, since there’s not enough social housing and rents in the private market are high.

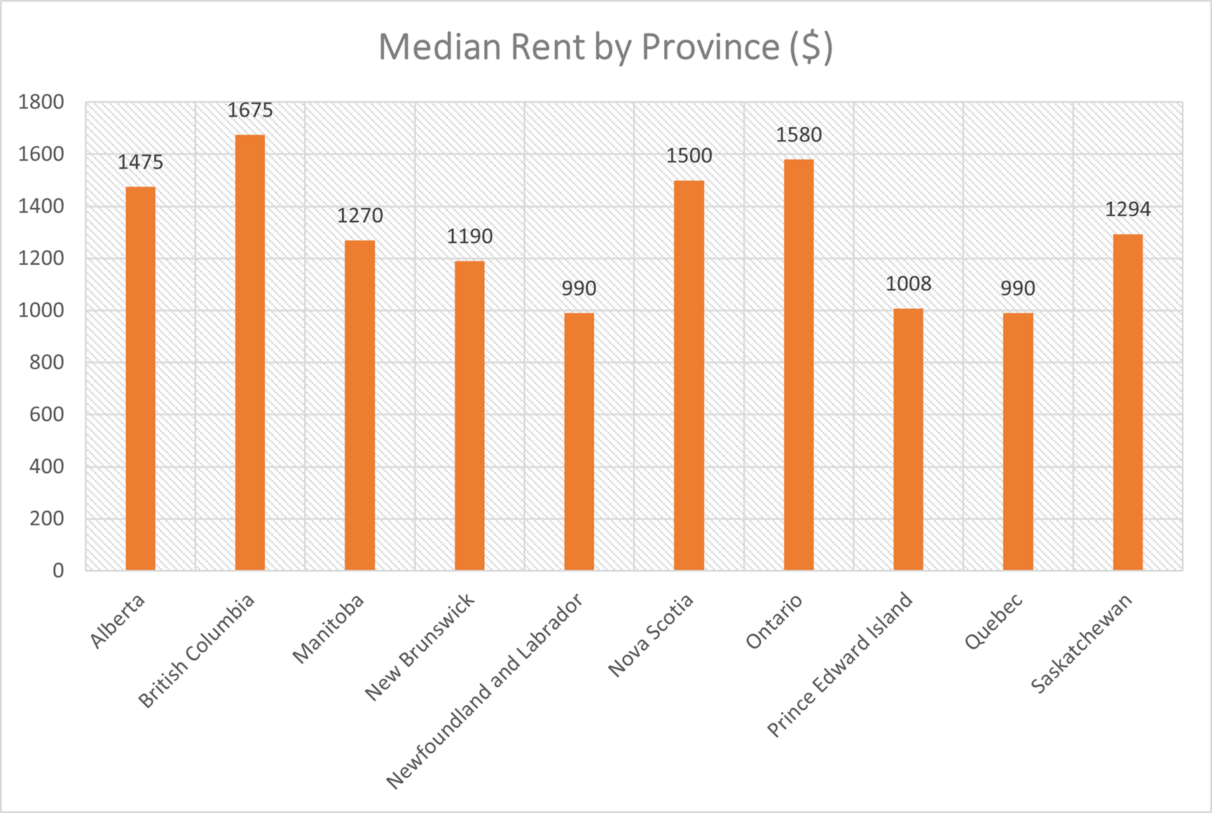

Statistics from Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation show that in October 2024, Nova Scotia’s median rent was $1,500, the third-highest among the 10 Canadian provinces.

Source: Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, median rent in primary rental market by province in October 2024

“Most of the people who live in Nova Scotia are just one or two paycheques away from being in a situation where they need to access shelter services. If you lose your job suddenly, if you become ill that you can’t go to work, you will lose your home,” said Roberts.

“It’s a nationwide issue, but Nova Scotia particularly since it’s not a high-income province.”

In March 2025, four residents moved out of Beacon House shelter village to permanent homes. Four more moved in.

For Roberts, the best goodbye is when someone says, “I never want to see this place again.” And she replies, “Thank you. Stay housed.”

About the author

Lu Fan

Lu Fan used to be a documentary filmmaker in China. She moved to Halifax in 2024 to learn journalism and experience a different life.