Annapolis changes tack in decade-long legal battle

Developer, HRM wrestle over special planning area next door to potential parkland

caption

Developer Annapolis Group appeared in court on Nov. 5 in its long-running legal dispute with HRM.Six months after the province opened the door for development near the proposed Blue Mountain–Birch Cove Lakes site, a decade-long legal battle over the land has taken a dramatic turn.

On May 16, Nova Scotia designated the Highway 102 West Corridor Lands a special planning area. The 630 acres of land encompassing the area is owned by Annapolis Group and B.D. Stevens, with housing and community development planned for the site. The designation triggered next steps for development.

The special planning area designation disrupts the long-running and high-profile civic court case pitting the developer against the city — Annapolis Group Inc v Halifax Regional Municipality. Related stories

How did the case start?

Starting in the 1950s, developer Annapolis Group began buying land in the Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes area.

In 2007, the municipality zoned that Annapolis land into two parcels –- 280 acres for an urban settlement, now designated the Highway 102 special planning area, and the remaining 701 reserved for future use.

A decade later, in 2017, Annapolis Group sued the Halifax Regional Municipality for $120 million, accusing it of effectively ‘taking’ its property, or ‘de-facto expropriation,’ after many unsuccessful development applications.

Annapolis claims the zoning restrictions deprive them of reasonable use of their land and say they are owed compensation.

Furthermore, they claim the city had acquired an “advantage” because the reserved portion was being unofficially used as an urban park, with hiking trails and swimming holes throughout.

The municipality appealed, saying Annapolis’s claim doesn’t fit the definition of de facto expropriation.

The case eventually ended up in the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in favour of Annapolis in 2022. That ruling changed the legal framework for de facto expropriation claims and cleared a path for the company to proceed with its lawsuit against the city.

“It’s a complete change from the previous law,” said Jim Phillips, a law professor at the University of Toronto.

The revision of the law drew criticism from legal firms and experts across the country.

Where is the land?

Annapolis’s land extends to the western boundaries of the Highway 102 special planning area, between Kearney Lake Road and Lacewood Drive.

The first step in developing that land was a public engagement event on Wednesday, where Annapolis and B.D. Stevens presented their development proposals for the land, including low to high-density housing. Municipal representatives were at the event, and residents showed up in droves to share comments and concerns.

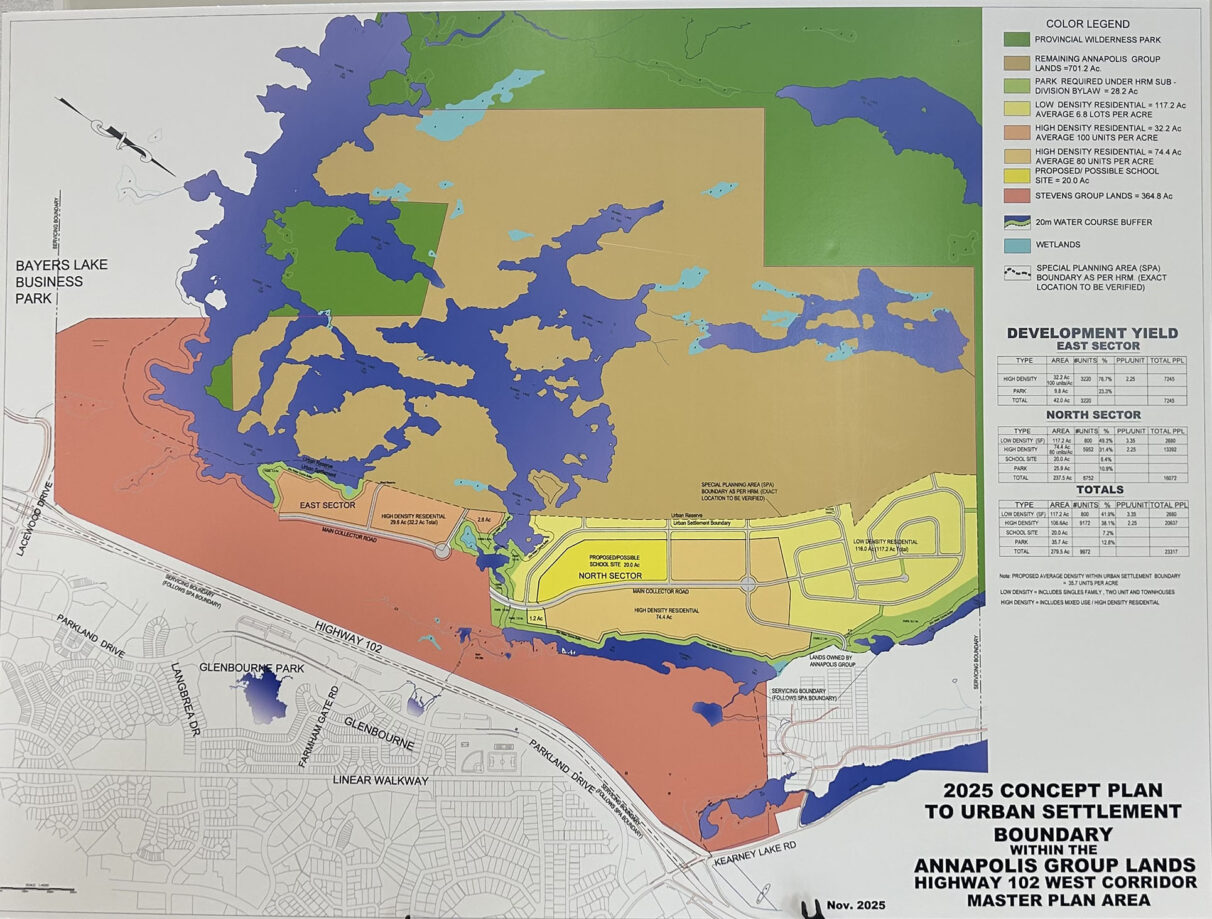

caption

This is the 2025 concept plan for Highway 102 special planning area development proposed by Annapolis at a public hearing earlier this week.Mary Ann McGrath, chair of Friends of Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes and a former MLA for Halifax-Bedford Basin, spoke to The Signal about the Annapolis lands.

“Everybody I know that grew up around here has been walking those trails their entire life,” she said. She argues that Annapolis’s land is an essential access point to a potential national urban park. Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes is currently being considered for potential development as a national urban park.

“One of the best national urban parks in the country is almost inaccessible because it’s completely surrounded by private land,” she said.

She is concerned that if the city does not expropriate Annapolis’s land, the park won’t exist. McGrath argues that the land should have been fully acquired decades ago, but the city has never wanted to go through the process.

“You don’t often hear about land expropriated for park purposes because it’s not seen as critical,” she said. “But it happens and it can be done, and it needs to be done.”

According to Ross Grant, the city’s lead planner for the special development area, “The municipality will look at opportunities for acquiring additional lands to potentially add into the park.” He declined to specify which lands would be considered.

What’s next with the lawsuit?

Following the special planning area designation, which triggered the official planning process on the Highway 102 West Corridor Lands, Annapolis filed a motion to the courts to amend their initial claim to de facto expropriation.

In their initial $120-million claim, Annapolis argued that they did not foresee ever being able to develop on their land. With the SPA designation, this is no longer true.

Annapolis’s revised claim asks for $170 million to compensate for their remaining land under reserve, land maintenance and the temporary development restrictions.

According to Annapolis, the special planning area designation “arose and was approved very quickly, near the scheduled end of this trial, and (was) surrounded by a halo of claimed solicitor-client privilege.”

Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice John Bodurtha, who is hearing the case, has yet to release his decision on Annapolis’s submission to amend their claim following the motion in court on Nov. 5.

About the author

Olivia Nitti

Olivia is in the One-Year Bachelor of Journalism program at the University of King's College.

Leave a Reply