‘A new and thoroughly modern city’ emerged in Halifax following devastating 1917 Explosion

caption

Temporary housing was built in 1918 for those made homeless after the Explosion.After the Halifax Explosion, the city moved fast to shelter thousands made homeless by disaster

caption

The buildings were home to about 2,500 to 3,000 people made homeless by the Explosion in 1918.Halifax has had to deal with large numbers of homeless citizens in the past. Today, there are camps of homeless people in tents scattered around the city and several shelters that seem to be bursting at the seams.

But following the Halifax Explosion in December 1917, the city was forced to find immediate shelter for many thousands of people left unhoused. The disaster levelled half the city and left 25,000 people without adequate shelter, not including the 6,000 left homeless.

Those whose homes were destroyed were sheltered in any available undamaged structure, including hundreds of tents on the Commons. These military tents were canvas and equipped with cots, oil stoves and blankets.

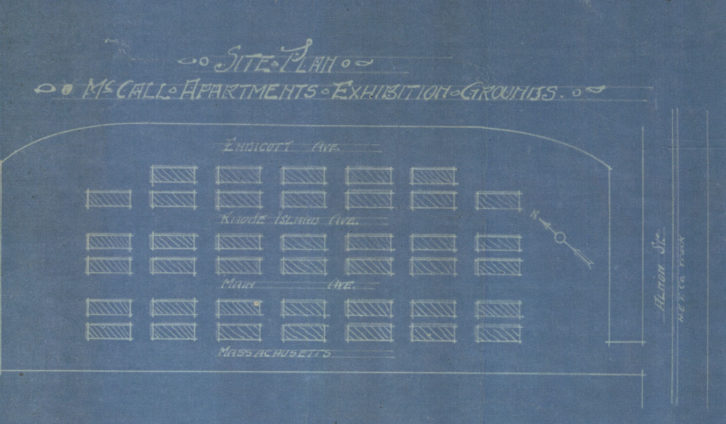

caption

The blueprints for all future housing built on Exhibition Grounds, at the corner of Almon and Robie streets, Halifax, in 1918.‘Getting it done quickly’

“The tents were super temporary,” said Michelle Hébert, social worker, journalist, and author of Enriched by Catastrophe: Social Work and Social Conflict after the Halifax Explosion.

“And most of them stayed empty that night because a lot of people whose houses had been damaged wanted to stay with their property or didn’t trust how flimsy a tent was.”

By the time the Halifax Relief Commission was appointed in January 1918, temporary housing was well underway across the city. The commission was charged with the city’s reconstruction and had $21 million at its disposal, donated by the public and by Canadian, British and other governments.

By March 1, 1918, 832 modern, self-contained flats had been constructed to house those without permanent shelter. During the same period, the relief committee had also processed over 3,000 repair orders to houses.

Why was this housing program ramped up so quickly in 1918 when it is taking months for housing for the homeless to be built in 2022?

“I think the difference is that there was such a commitment to getting it done quickly, there were a lot of people who really had nowhere to call home,” said Hébert, comparing the HRM’s current housing strategy to the commission’s over a century ago.

“There was an estimate at the time that the commission was building about an apartment an hour.”

‘Beautiful, neat, sunny, clean and substantial’

People could move into the tenement-style apartment buildings by March 1918, with the Hydrostone and the rebuild of the North End complete in 1921.

While equipped with plumbing and electricity, like the military tents, the buildings were seen as a temporary solution.

caption

Oct. 9, 1918: The Halifax Relief Committee was responsible for construction of the McCall Apartments as temporaryhousing on the Exhibition Grounds at the corner of Robie and Almon streets.

“The apartments were meant to only last for five years so they were not really well constructed,” said Hébert.

“You know, they were meant to be put up really quickly and torn down really quickly as more permanent housing was built in other parts of the North End.”

In total, there were around 40 two-storey buildings, with almost 300 to 400 apartments altogether.

According to Hébert, apartment buildings were built on large pieces of public land near what is now the Halifax Forum on Boston street. There were additional buildings constructed on the Garrison Ground by Citadel Hill and the Exhibition Ground.

An illustrated poster printed in 1919 portrayed “a new and thoroughly modern city underway in the north of Halifax.”

It also described the Hydrostone construction as “beautiful, neat, sunny, clean and substantial.”

Around the same time, the North End rioted in protest of their housing conditions following the Explosion because they didn’t feel like their perspective as a community was being included.

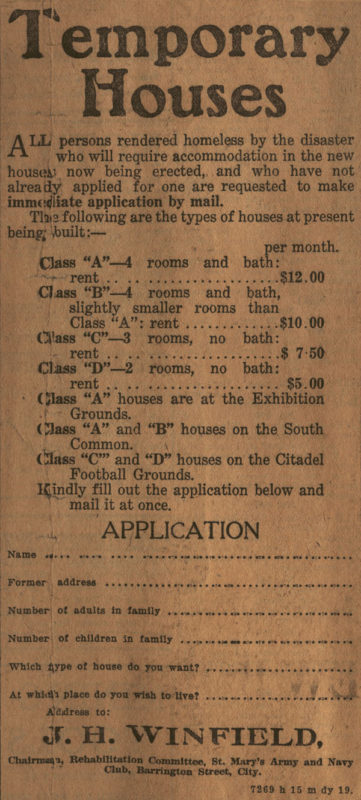

caption

An advertisement for temporary housing from The Halifax Herald, Jan. 15, 1918.“I remember reading a comment in one of the committee’s minutes books from one of the (council) members saying, ‘Well, if we give the North Enders any say, you know, that’s a democracy,’ ” said Hébert. “ ‘It just means that they’ll be free to build another slum.’ ”

Prior to the explosion, although the Poors’ Asylum, or Poor House, was maintained by the city for the ‘utterly destitute’, the churches were responsible for homeless children, ‘fallen’ women and girls, and juvenile offenders, with some financial support from the municipal government.

“I feel like that kind of attitude is still very prevalent, you know, people had to be considered worthy of receiving the help … and we see something very similar now,” said Hébert.

In 1918, in order to receive aid from the Commission, individuals were not allowed to drink and if they were a woman, they couldn’t entertain men in their house.

“Our attitudes haven’t changed a whole lot, which is really discouraging. I would hope that decision-makers today will look at what happened in the past and how far-reaching decisions can be,” said Hébert.

“We’re still experiencing fallout from the decisions that were made 104 years ago.”

Temporary shelters built by Halifax Mutual Aid, an advocacy group for the homeless, dotted many green areas around Halifax until last August, when regional police dismantled several that were occupying space outside the old Memorial Library on Spring Garden Road.

It takes Halifax Mutual Aid $1,400 in materials to build one of these small, watertight, and insulated shelters. They are intended as a temporary solution to allow unhoused people safe, private spaces to stay healthy, regardless of the weather.

Since December 2020, 53 people have inhabited one of HMA’s crisis shelters. There are currently 416 unhoused people in Halifax Regional Municipality.

In August 2021, regional council approved the creation of two modular unit sites, in Halifax and Dartmouth, through the Affordable Housing Association of Nova Scotia, a project that has now run a tab of almost $5 million.

The Dartmouth units began to be occupied on Jan. 16, six months after council’s approval, and perhaps two months before construction on the Halifax site will start.

caption

A woman inside one of the modular homes built after the Halifax Explosion in 1918.