Activists say human trafficking ‘should be talked about like we talk about the weather’

More conversation, reduced stigma needed to keep up recent progress and create change

caption

Linda MacDonald (left) and Jeanne Sarson have been fighting human trafficking in Nova Scotia since the 1990s.Two retired public health nurses say it’s actually good news that we’re hearing more disclosures of human trafficking in Nova Scotia.

Jeanne Sarson and Linda MacDonald are now full-time activists and educators in Truro, fighting against human trafficking.

“I think it’s important to know that it’s an age-old crime,” MacDonald said. “It’s been happening under our noses for many, many years.”

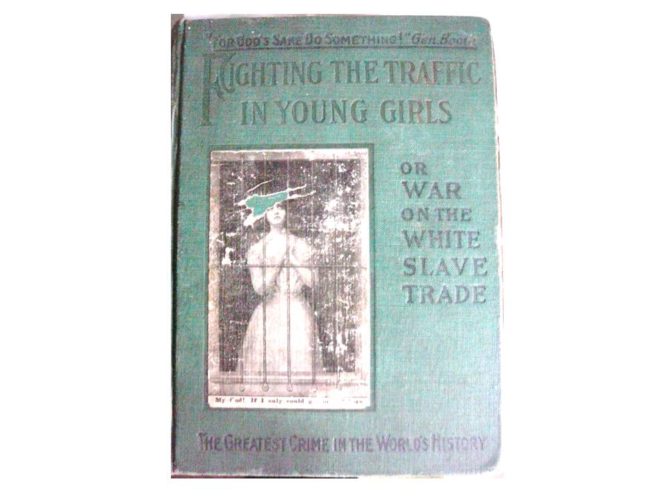

They point out a book they discovered from 1910 by Ernest Bell called Fighting The Traffic in Young Girls or The War on the White Slave Trade. In it, Bell states that over 100 young women and girls had been trafficked into Boston and that one-third of them were from Nova Scotia. Related stories

caption

Ernest Bell’s 1910 book Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls shows human trafficking of Nova Scotian women and girls is at least a century-old problem.“When you read the book,” MacDonald said, “the tactics back then are the same tactics that are going on today.”

For many people, human trafficking still conjures up images of kidnappings taking place overseas like in the movie Taken. But according to Statistics Canada’s most recent report from June 2020, only about 12 per cent of sexualized human trafficking cases in Canada involve abduction or forcible confinement. In the vast majority of incidents, the perpetrator is a person the victim knows, most commonly a friend or a romantic partner.

As Sarson and MacDonald point out, it can be a family member too. Statistics show the victims are overwhelmingly young women and girls, but anyone can be targeted.

Cpl. David Lane of the RCMP and the provincial Human Trafficking Unit said often girls and women don’t even recognize themselves as victims of human trafficking at first because there’s a lot of psychological manipulation involved.

The perpetrators tend to follow a predictable process of grooming and manipulation.

“It wouldn’t be uncommon for someone to call and say that their daughter met Prince Charming,” Lane said, “someone who they’re very in love with that understands them better than anyone before.”

Next, he said, they start to withdraw from family and friends, maybe even delete their social media accounts. There may be changes in physical appearance like their hair and nails being done, or unexplained gifts.

“None of those scream criminal offences,” Lane said, “but to us, they’re all indicators of the first parts of human trafficking, and we want to look at it as early as possible.”

The Statistics Canada report also noted the known corridor for trafficking victims between Nova Scotia and Ontario. Lane confirms that many Nova Scotian victims are trafficked out of the province and into larger centres on what they call “the circuit.”

Making progress

The Nova Scotia Human Trafficking Unit that Lane is part of was created in 2019. It is made up of specially trained RCMP and municipal police officers using a victim-centred approach specifically to deal with multi-jurisdictional human trafficking cases.

In February 2020, the province announced it would provide an additional $1.4 million a year over the next five years, to support new and current initiatives fighting human trafficking and supporting survivors.

It included funding to hire victim support navigators, the creation of six province-wide positions from the Additional Officer Program for dedicated sexual violence and human trafficking, and funding to hire a dedicated Crown attorney for human trafficking cases.

The Trafficking and Exploitation Services System (TESS), created last year, is an inter-agency provincial partnership of over 140 community leaders and professionals working on education and support for victims. Charlene Gagnon of the YWCA, one of the partner organizations, said since COVID-19 they’ve trained over 1,000 frontline service providers to recognize and respond to human trafficking in every sector.

Last March, Sarson and MacDonald lobbied the Truro Police Service governance board to request that human trafficking be listed as one of the police’s three annual priorities. The police agreed and renewed that commitment for a second year, listing human trafficking as a top priority for 2021.

Sarson and MacDonald also lobbied the Nova Scotia Department of Justice last year to allocate one of the Additional Officer Program positions for combatting human trafficking to Truro police. Truro police Chief Dave MacNeil and Heather Fairbairn, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice, both confirmed the allocation, but said the position is not yet operational.

Understanding the scale of the problem

According to Statistics Canada, Nova Scotia has the highest rate of human trafficking in the country, followed closely by Ontario. The two provinces have seen trafficking at rates around double the national average.

Cpl. David Lane, Halifax Regional Police and the Nova Scotia Public Prosecution Services all confirm that human trafficking cases are by nature complex. They often involve a group of perpetrators working together, cases often cross multiple jurisdictional borders and there are often several additional charges involved. The victims’ often fear law enforcement and their perpetrators, which means they’re less likely to report.

These factors combined make it difficult to get a handle on the scale of these crimes in our province.

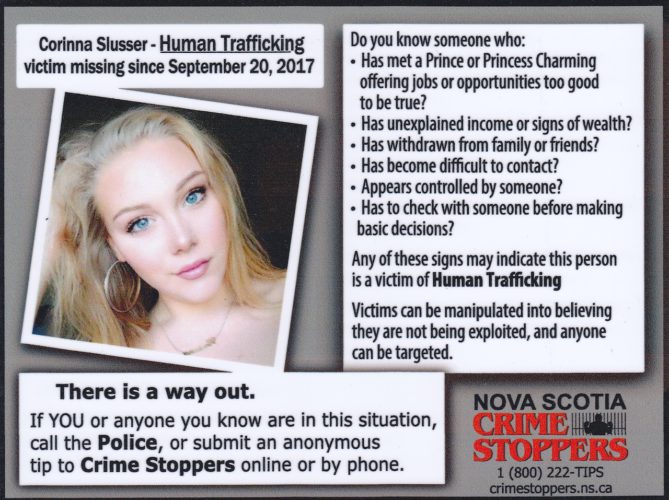

caption

Crime Stoppers created these posters for use in public bathrooms to raise awareness of human trafficking in the province.The Halifax Regional Police and the RCMP said it would take considerable time to gather accurate Nova Scotia statistics on human trafficking charges laid in recent years.

According to a survey of available news releases from Halifax Regional Police, police have charged 18 people with human trafficking charges since 2016. A similar survey of RCMP releases show they have charged seven men with human trafficking charges since 2017 in Colchester and Pictou counties.

The number of victims coming forward may be climbing.

“What we’re finding,” Lane said, “is when we’re changing the language of human trafficking to [describe] what it actually looks like in real life, we’re getting a lot more disclosures.”

Difficult to prosecute

Melissa Foshay of the Nova Scotia Public Prosecution services said in an emailed statement that in addition to the complications of multiple jurisdictions, perpetrators and charges, human trafficking victims are often reluctant to testify in court, which can be a key piece of evidence. Due to the extensive emotional manipulation, the victim either does not believe the trafficker did anything wrong or does not want to see harm come to the person they consider to be their boyfriend or girlfriend.

In addition, Foshay said, the process of preparing to testify in court can be very difficult for a human trafficking survivor, and often they are scared that the trafficker might retaliate.

Statistics Canada shows human trafficking cases average four times more charges and take twice as long to complete as other cases. Six in 10 completed human trafficking cases are stayed, withdrawn, dismissed, or discharged, and cases not processed as human trafficking are more likely to result in a guilty decision.

“Considering this,” Foshay said, “human trafficking cases often require a co-ordinated approach across all jurisdictions involved in order to be successful.”

Keeping the conversation going

Sarson and MacDonald first became aware that human trafficking was happening in their community in 1993. They had started a private clinic in Truro specifically for people recovering from violence. One evening a woman walked in saying she was suicidal and needed help. Over the following weeks, she told them of the organized, family-based torture and sexualized trafficking she had been subjected to since infancy.

They have been working on this issue for almost three decades now. Sarson said in 2018, she presented to Colchester County council requesting they add a small section to their newsletter detailing what is being done in the county to prevent violence against women and girls.

“The response I got was that if they did that, nobody would want to come to live in the community,” Sarson said.

MacDonald said she approached the schools, malls, and other high traffic areas requesting they consent to hang Crime Stoppers posters listing the warning signs of human trafficking in public bathroom stalls. But, she said, only the Truro public library and a few small businesses were willing to post them.

“People didn’t want to put the [posters] up on the bathroom doors, because it’s like admitting human trafficking happens in the town,” MacDonald said.

Sarson and MacDonald are not slowing down, though. They will be keeping the conversation about human trafficking going with speaking engagements at two upcoming international conferences and releasing their book, Women Unsilenced: Our refusal to let torturer-traffickers win!, later this spring.

“This should be talked about like we talk about the weather,” Sarson said.

“If we just put it out there in everyday conversation, we’ll all be informed. And we’ll all respond in a way that will change our society.”

About the author

Rose Murphy

Rose Murphy is a multimedia journalist in Nova Scotia. She is interested in stories about unusual characters, small business, resilient communities,...

L

Linda MacDonald

J

Jeanne Sarson