Ahead of its time

caption

The Micmac News is archived at the Mi’kmaq Resource Centre at Cape Breton University.The newspaper that defined Mi’kmaw journalism

In Grade 12 at Hants East Rural High in 1987, Maureen Googoo was approached by a friend with a job posting. The Micmac News was looking for summer students. Googoo applied and shortly before graduating, received good news: she was in.

Equipped with a tape recorder, fresh notebook, and new Pentax camera, “I biked around my home community of Indian Brook First Nation for the summer, just looking for people to talk to,” Googoo says. Reporting for Micmac News “convinced me I wanted to work in journalism.”

Developed in 1965 in Membertou First Nation, the Micmac News was an Indigenous-owned-and-run monthly newspaper that covered the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia. Micmac is an antiquated spelling and pronunciation of Mi’kmaq.

Growing up, “there was always a copy of Micmac News on the table,” Googoo says. The paper covered every aspect of life including sports, Mi’kmaw language lessons, and profiles of community members such as famed poet, Rita Joe.

Circulation in March 1972 was roughly 5,000. Nova Scotia’s Indigenous population that year was 4,890 — nearly half of all First Peoples in the Maritimes.

Politics were at the forefront of the newspaper, which was just as focused on holding Mi’kmaw leadership accountable as it was the provincial and federal governments.

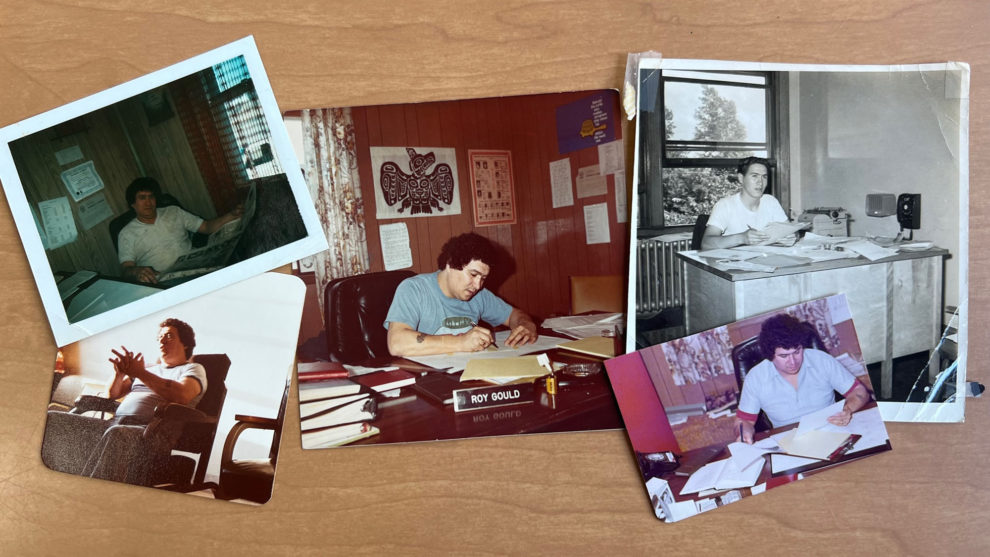

Nineteen-year-old Roy Gould was creating early copies on a typewriter in his bedroom.

“The Micmac News, for some of you, may be just reading matter but for the greater number of us it is a major breakthrough for self-expression and shows great possibilities for communication and a closer bond between Indians of Cape Breton,” Gould wrote in the inaugural edition.

Initially, the newspaper only covered the five Mi’kmaw communities in Unama’ki, or Cape Breton. Scattered across the island, their remoteness often kept them apart. United under one newspaper, the Micmac News became a shared resource.

Roy Gould died in 2004. His brother, Duncan Gould, is keen to point out he recognized how journalism served their community. “Information is power. He was all about empowering and enriching people.”

caption

Snapshots of Roy Gould (1946-2004) throughout his time at the Micmac News. Gould was also the youngest Chief in Canada at the time of his 1969 election to Membertou First Nation at age 23.Bold and bountiful

The newspaper entered its heyday as the Mi’kmaq themselves were becoming more emboldened. “If you look at those former papers … It shows a reawakening of the Mi’kmaw spirit. They were very cavalier times, renaissance times,” says Clifford Paul, a former journalist. He started at the Micmac News as a summer student in 1982.

Having access to those editions 40 years later is miraculous. Academics “were not really documenting Mi’kmaw history. It is one of the few written sources of political history of the Mi’kmaq at that time,” says Tara Johnson. She’s a Mi’kmaq resource coordinator and research assistant at the Mi’kmaq Resource Centre at Cape Breton University, where the newspaper is archived.

Today, physical copies are in 22 green, leather-bound binders. A few scattered editions are missing, but the nearly complete collection is one of the centre’s most prominently featured holdings, sitting atop the shelf of archived print materials.

In 1976, the newspaper began using funds from the federal government’s Native Communications Program. For the first time, staff writers were employed. The paper’s page count doubled to around 40. Coverage more consistently included First Nations communities beyond Nova Scotia. Armed with reliable funding, more major stories were told.

Junior and genocide

The paper covered Donald Marshall Jr.’s case extensively. In 1982, the Mi’kmaw man — wrongfully convicted of murder — was released from prison, then exonerated a year later. “I think it was the first time a lot of mainstream, white reporters actually heard about the challenges that were going on in Indigenous communities in terms of justice,” Googoo says.

The newspaper’s fearless coverage led to Marshall’s vindication. “I am a free man today because the Micmac News refused to let my story die … ,” Marshall said in the Sept. 1990 edition.

Another groundbreaking story was an exposé on the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in 1978. It was known as the Shubie School or the Resie, according to the newspaper, and “Regardless of its name, for most of its existence it was Hell.”

The horrors of the institution — the only residential school in the Maritimes, from 1930 until 1967 — were still fresh. Yet the Catholic Church continued to hold great influence in Mi’kmaw society.

Covering the story was courageous. The Micmac News wasn’t afraid to call out religious leaders, specific nuns and the Canadian government for aiming to destroy the Mi’kmaq people, culture and language through cultural genocide.

“What you had was a very systemic form of racism in the media,” says Duncan Gould. His brother Roy “was really trying to break beyond that back then. He was way ahead of his time.”

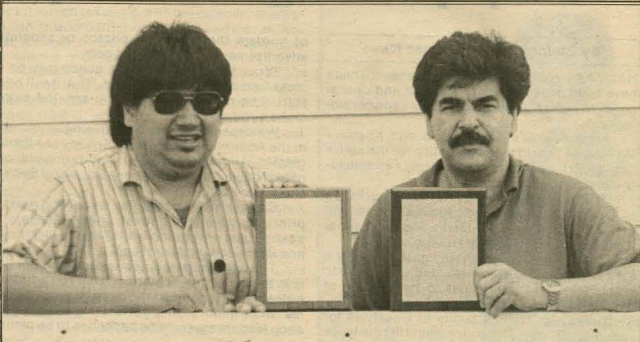

caption

Reporter Clifford Paul (left) and editor Brian Douglas showcase awards won at the second annual Aboriginal Multi-Media Festival in Halifax in 1988. Paul’s award was for best cultural feature story on a piece about Mi’kmaq war veterans, while Douglas’ award was for editorial commentary on the Donald Marshall Jr. inquiry.Hyperlocal focus

The paper’s coverage within Mi’kmaw communities set it apart. Clifford Paul found inspiration as a journalist by sharing stories of what he calls ‘grassroots people.’

A summer student once complained there was nothing happening in her hometown of Eskasoni, the largest Mi’kmaw community in Nova Scotia. Paul asked the girl what the population was. He told her each person has a story, then sent her back to Eskasoni to find one.

It’s this community-minded reporting that Paul was taught by his editors and hoped to pass on to the younger journalists he mentored. “Sure, politicians come and go. But there are people in your community who are the strength of the nation, they are at the forefront. And they deserve that front page.”

End of an era

After finding her calling as a summer reporter in 1987, Googoo hoped to be the editor one day.

Her plans were shattered in 1990. Funding was decimated in a federal budget that closed 14 other Indigenous newspapers across Canada under Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government.

The Micmac News had no path forward.

Brian Douglas was the editor at the end. He felt this was more than a simple budget slash, writing in the final edition, “By cutting off issue oriented native newspapers, many of which have been highly critical of government, Ottawa hopes to silence aboriginal people.”

caption

Maureen Googoo receives the best summer student news reporter award following the summer of 1987; she also tied for best photograph. Googoo travelled to the newspaper’s office in Membertou to help the editors during deadline week.Paul concurs. “I think we lost our funding because we did such a great job,” he says. “Look at that old style, check those old papers. I’m happy with that legacy.”

Duncan Gould says the newspaper’s death was “cataclysmic” for Roy and his employees, because it “represented true journalism.”

The Micmac News was briefly revived in 1991 with Paul as one of its editors in an attempt to survive purely on advertisement revenue. It lasted through the year before dying a second and final death.

The Mi’kmaq were left without meaningful media coverage, Googoo says. “There was nothing after ’91 holding Indigenous leadership accountable … a lot of leaders got spoiled.”

Definitions

Amidst the downfall, a new publication arose in November 1990: Mi’kmaq-Maliseet Nations News. It was funded and run by the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq, a tribal council organization.

To former editor, Tim Bernard, the difference between this new publication and the Micmac News remains clear. “We tended to stay away from internal political issues — we weren’t pitting community against community.”

The publication still exists. With no journalists on staff, it relies on submissions and aims to celebrate Mi’kmaw culture and people, an aspect Bernard says has historically been missing in mainstream media coverage. “Some people will challenge the term ‘newspaper,’ because we’re not trying to divide people and create controversy in communities. We still stick to that ‘good news’ story.”

While the publication was started by some former employees of the Micmac News, Googoo says it’s no replacement. “It’s the same as going through public service announcements … It’s not news, and it’s not journalism,” says Googoo.

So, what is the answer to Micmac News? For many, it’s Googoo herself.

Community

Googoo studied political science at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax — she also earned a journalism degree from Ryerson University, now known as Toronto Metropolitan University — and took a year off for a paid CBC Radio internship. She later worked at the Chronicle Herald.

Googoo felt increasingly disconnected from Indigenous stories and the significance of telling them. “I wanted to do that, but there were always barriers and discouragement,” she says. This frustration led her to leave journalism for a communications role with the Union of Nova Scotia Indians in 1998. The Marshall decision drew her back.

Googoo opened the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network bureau in Halifax and ran it for more than six years.

In 2006, she was chosen from a “pool of extraordinary applicants” for a master’s degree in journalism at Columbia University in New York. Studying digital media, she had an idea.

Ku’ku’kwes News, pronounced “Goo-goo-gwes”, launched in 2015, focusing on Atlantic Canada. Googoo is the independent outlet’s sole journalist. “The whole premise of me doing the website is to try to bring back that sense of community that Micmac News fostered,” Googoo says.

She believes mainstream coverage of Mi’kmaq communities has improved since the time of Micmac News, but many stories are still written for a non-Indigenous audience. “I don’t want to do that. I want to do the stories [Indigenous] people care about, stories that prompt a call to action for them.”

One of Googoo’s mentors was Clifford Paul. He recalls her time at the Micmac News with pride. “The work that we had done opened doors for people such as Maureen, who wanted to take it further,” Paul says. “It’s like the edge of a sword.”

Journalists have that edge, “and today, unless you’re doing something like what Maureen is doing, that edge will get dull.”

Editor's Note

Residential school survivors and their families can call a 24/7 National Indian Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.

About the author

Sam Farley

Sam is a fourth-year King's journalism student from Boston.

J

Joan D Paul