Barred rising stars

caption

Em Burry sits on their bed while holding their guitar. They are a young artist carving their path in a shaken industry.Up-and-coming musicians face an uphill battle in the COVID era

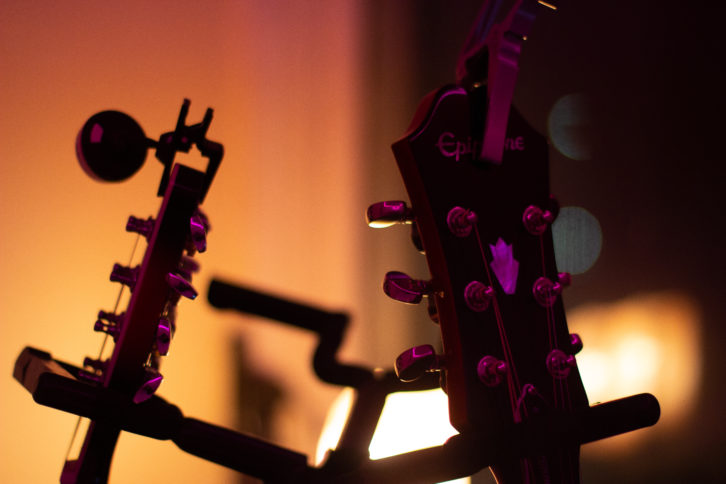

With a blue Epiphone on their lap, Em Burry sits on a bed for a photoshoot. The 26-year-old plays the guitar out of reflex. As the shoot progresses, so does their immersion in the instrument. The melodies increase in complexity as they shift from strumming open chords to picking elaborate patterns, their fingers flowing across the guitar’s dark brown laurel fretboard.

Occasionally, they remind themself to look up at the camera. Each time with a smile and a laugh, as if they’d been awoken from a daydream by the sound of the shutter closing.

Burry is an emerging musician in Halifax, doing everything to grow an audience, support their music and stay relevant as COVID batters their industry. Tasks that sound challenging, but are essentially impossible. On January 30, 2021 they released their debut EP, Yellow Paint. It was recorded on the cusp of COVID. Most tracks were done in studio but because of the shutdown, some vocals and mixing had to be done remotely.

March 22, 2020

Burry and their band were going steady. With shows on a monthly basis, a tour booked to Toronto and Yellow Paint in the works. After three years of releasing singles, they were starting to gain traction.

Not having an established fanbase going into this, and not being able to grow an established fanbase by doing shows has been difficult. Em Burry

Then, on March 22, 2020, former Premier Stephen McNeil declared a state of emergency to keep COVID from spreading.

That press conference cleared their calendar. The consistent live performances that helped get the word out, and engage with an audience: gone. And with them, potential new fans who would bring them closer to music industry job security.

“Not having an established fanbase going into this, and not being able to grow an established fanbase by doing shows has been difficult,” they say. “Trying to do that using social media is harder than it looks.”

The potential fan walking into a show has morphed into a potential follower scrolling through Instagram, which demands that artists produce more content and stay active to cling to relevance. This may be easy for a popstar raking in millions of streams, but for the working-class musician it’s another thing expected of them if they want to pursue their passion.

And while it would be nice, landlords don’t take passion over e-transfer.

caption

For artists trying to break into the industry, the pandemic comes with added financial pressure and concerns about the ability to grow a dedicated fanbase.Emerging musicians are caught in the midst of a panicked industry. Chris McDonald, associate professor of ethnomusicology at Cape Breton University, says COVID has “blown it right up.”

A weird new era

In one way, artists now are in a better place than they would have been 25 years ago. McDonald says that because of social media, musicians today won’t disappear from their fans lives like they would have before, which is “a positive thing for artists in a crisis like this.”

But social media can be additional labour with little kickback. It pits rising musicians against established artists in a competition for attention.

When major label artists have a new release, they already have a network in place and fans willing to stream music in their sleep. This gives them access to attention on demand. They also have money to spend on boosting posts or buying ad campaigns, and “if you don’t have that capital, it’s hard to get in front of people that way.”

Musicians are treated more like “raw material rather than agents in the system.” The emotion channeled into their creative work being viewed by corporations as another thing to be bought and sold to generate capital. McDonald says that there is a clear and extreme relationship between the music industry and economic trends

“Gig economy” is usually a term used to describe ride sharing services like Uber, but McDonald says “that’s what musicians have been doing since God knows when.”

Emerging artists today aren’t as much gigging musicians as they are gig workers. They have to diversify their income streams and forge a presence on every possible platform to gain an audience and become established.

No money down

Burry says that there been “a lot of opportunity to be writing, recording and releasing,” but not nearly as many opportunities to make money.

The old model of touring to support an album in hope of boosting sales and royalties vanished long before March of last year. Over the past decade, tours and live shows have gone from something to boost revenue from album sales to a primary income source. The business of music has changed again during COVID, removing this key part of the equation.

For an up-and-coming artist, the effect isn’t just noticeable, it’s an ever-present worry.

Since lockdown, they have played three shows to a live audience. With social distancing comes limited capacity, and what was a decent payout becomes an expense. Burry notes that not being able to perform regularly has been a “big hit on finances.”

While there are economic supports available, submitting a grant application doesn’t guarantee funding from Factor or Music Nova Scotia. There’s only so much to go around, and many musicians across Canada are in need of funding.

caption

While there are grants available for artists, the revenue found from album sales is a ghost of the past. Streaming has become the norm, changing the value of music.The payout from streaming services, such as Spotify, pales in comparison to what can be made from live performances and merchandise. Spotify only pays fractions of a cent per stream ($0.0027), making it an unsustainable source of income.

That’s around 364 streams to make a dollar. To earn full-time minimum wage in Nova Scotia—40 hours a week at $12.95 an hour (as of April 1, 2021)—an artist would need 191,851 streams a week. This doesn’t factor in other fees, expenses and cuts taken by streaming services.

The pressures of streaming can build on emerging musicians. Leading to stress and even doubting their ability as a performer.

Burry tries not to let this pressure get to them, but admits there are times when thoughts like “I’m not getting streams. I’m a failure,” crawl into their conscious. They know it isn’t true, but it can be a hard feeling to shake.

The onus is on artists to find new ways to monetize and promote their craft, rather than on the industry to support them. And the pandemic has done nothing but reinforce this. COVID is the last thing anyone in the music industry needed.

There are models like Bandcamp or Patreon, where fans can purchase music and content directly from creators. But since fans have access to hundreds of millions of songs through streaming services, pushing a digital album is a tough sell.

Prying the floodgates

Liz Pelly is a music journalist and adjunct instructor at New York University. A majority of her work focuses on the relationship between technology and artist exploitation. Her recent piece for Real Life Magazine, “Socialized Streaming: A case for universal music access,” discusses alternatives to corporate streaming.

The model gripping the industry is “designed for the benefit of major label artists.” Pelly says in an interview.

Up-coming musicians are at a disadvantage. Competing for streams against artists with corporate backing and millions of dedicated fans. This model exacerbates the “intense biases” of the industry.

One of the big disadvantages of the current music status quo is how it creates this passive listening environment.Liz Pelly, music journalist

In her piece, Pelly writes in favour of decentralized streaming models. Where the power and cash flow aren’t relegated to a handful of major corporations.

She points to cooperative streaming service Resonate, started in 2016. Users of on this service pay each time they stream a song until they’ve paid enough to buy it. Pennies at a time. Once they meet that threshold, they can listen to it for free.

Another model showing promise is a new reason to dust off your library card. Public libraries across Canada and the United States have started their own streaming programs that pay artists stipends. These programs also provide an opportunity for local musicians to get involved through things like curation and creating playlists.

“One of the big disadvantages of the current music status quo is how it creates this passive listening environment,” says Pelly, “which flattens out those important relationships that bring music communities together.”

But could these replace the centralized models of Spotify, Apple Music or Tidal? Probably not entirely, but they show what is possible. Making streaming more beneficial to artists by taking a different approach to organizing and funding. Giving them more control over how their work is distributed and consumed.

Suit, tie and hung out to dry

The East Coast Music Awards (ECMAs) will take place on May 5 in Sydney. The event is held by the East Coast Music Association (ECMA) and is a mix of performance, conference and awards ceremony that aims to celebrate East Coast musicians.

Tenille Goodspeed, marketing and sales manager for the ECMA, says that the organization is doing it’s best to support artists during the pandemic. While she would love to see every musician get out into the world, there is a “certain level an artist needs to be in order to be export-ready.”

The journey to become export ready is like a pipeline. If you’re into hockey, think of it like a farm-team system, where players move from a junior league like the QMJHL, to the AHL then finally to the NHL. The same is true for the music industry—it’s just less apparent at first glance.

Musicians have to develop the business side of their art, learning things such as cross-border banking, self-promotion on social media and how to hire a manager or agent. The goal is to prepare artists to negotiate business deals with delegates at conferences like the ECMAs.

Goodspeed says that the organization’s approach to supporting young artists is two-fold. Providing them with tools to further their career as well as showcasing opportunities so they can perform in front of delegates and “flex that creative muscle.”

But much like an athlete, it’s hard for rising musicians to carve a path outside of organizations such as the ECMA.

caption

Despite the challenges, Burry is determined to find their place, with some encouragement from their dog, Alice.Burry finishes the photoshoot and gathers their gear to head to a song-writing session. Guitar case in one hand, they pat their dog Alice, assuring her they’ll be back soon.

They put on their mask before leaving their apartment. A black mask with “Burry” stitched across it in simple yellow lettering. It’s not official merch, but rather a handmade gift from their father.

“We’ll just keeping doing our own thing,” says Burry, “people will see that we’re here.”

About the author

Alec Martin

Alec (they/them) is a journalist based in Halifax, with a focus on music and arts. Their work has appeared in The Coast and they are a member...

S

Stuart robertson